Songs of America: Patriotism, Protest, and the Music That Made a Nation

The city was thronged. On Thursday, September 3, 1936, tens of thousands of people lined the streets of Des Moines, Iowa, to catch a glimpse of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who arrived by train at the Rock Island station at noon. Troops from the Fourteenth Cavalry stood at attention as uniformed buglers greeted the commander in chief, who emerged from Pioneer, his private carriage, balanced on the arm of his youngest son, John Roosevelt, smiling broadly and waving to a cheering crowd.

Nearly half a century later, at least one admirer could recall the day in great detail. A young sportscaster at Des Moines’s WHO radio station had been visibly thrilled as he hurried to the window of his offices on Walnut Street to take in the motorcade. “Franklin Roosevelt was the first president I ever saw,” Ronald Reagan told a gathering of Roosevelt family and New Dealers at a 1982 centennial celebration of the 32nd president’s birth.

Speaking in the East Room, Reagan, now the 40th president, paid tribute to the Democrat for whom he had voted four times — in 1932, 1936, 1940, and 1944. “Like Franklin Roosevelt, we know that for free men hope will always be a stronger force than fear, that we only fail when we allow ourselves to be boxed in by the limitations and errors of the past.” The president then offered a toast: to “Happy days — now, again, and always.”

The reference was unmistakable, for Franklin Roosevelt and the song “Happy Days Are Here Again” were inseparable in the political imaginations of Americans. The song entered the nation’s political consciousness at the Democratic National Convention at the Chicago Stadium in 1932. Roosevelt, who was seeking the presidential nomination, had planned to have “Anchors Aweigh” as his theme song, reminding delegates and listeners on the radio of his tenure as assistant secretary of the Navy during the Great War. From his command post at the Congress Hotel, Roosevelt adviser Louis Howe listened to his secretary, a fan of “Happy Days Are Here Again,” sing it out for him. Impressed, the wizened political sent word to the hall to change course: “Happy Days Are Here Again” was now the FDR standard.

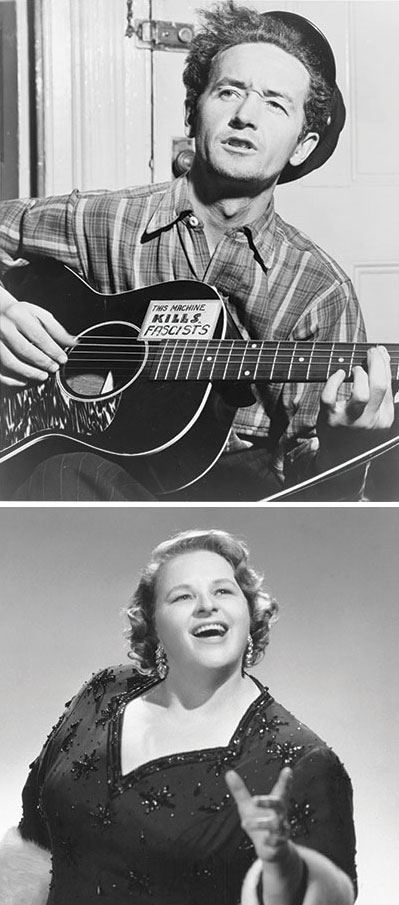

In 1938, the drift toward chaos and bloodshed in Europe prompted the composer Irving Berlin to excavate a song he’d written in 1918, “God Bless America.” He arranged for the singer Kate Smith to perform it on her CBS radio show on Armistice Day 1938, and Smith would record the number in early 1939. In the late 1930s, fearing Hitler, listeners did not have to think hard about what she meant when she spoke of “the storm clouds” gathering “far across the sea” or “the night” that required “a light from above.” Woody Guthrie, though, heard something else in Berlin’s verses: a triumphalism that portrayed America simplistically and sentimentally. And so Guthrie wrote a reply. Initially titled “God Blessed America,” it became “This Land Is Your Land,” a song that grew in popularity during and after World War II. (By 1968, Robert Kennedy was suggesting that “This Land Is Your Land” ought to be the national anthem.)

In wartime, the simpler the song, the more powerful it was, not least because life under fire was so emotionally complicated. The most moving music of the war was the music that moved the troops themselves — songs of longing and loss, of love and hope. There was “We’ll Meet Again,” “You’ll Never Know,” and big band numbers by Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, and others. It was the age of such songs as “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,” and Miller and the Andrews Sisters each had a hit with “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree (with Anyone Else but Me).” Miller, whose “Moonlight Serenade” was a signature song, lobbied to join the military once America entered the war. (Born in 1904, he was in his late 30s.) Bing Crosby wrote the government a letter of recommendation, saying that Miller was “a very high type young man, full of resourcefulness, adequately intelligent, and a suitable type to command men or assist in organization.” Commissioned in the Army Air Force, Miller set out, he said, to “put a little more spring into the feet of our marching men and a little more joy into their hearts.” Regular military bands resisted Miller’s attempts to bring the music forward from the Great War to the 1940s. “Look, Captain Miller,” one is said to have complained, “we played those Sousa marches straight in the last war and we did all right, didn’t we?”

“You certainly did, Major,” Miller replied, according to the story. “But tell me one thing: Are you still flying the same planes you flew in the last war, too?”

On a broadcast on Saturday, June 10, 1944, a few days after D-Day, he announced, “It’s been a big week for our side. Over on the beaches of Normandy our boys have fired the opening guns of the long-awaited drive to liberate the world.” The band’s opener that day was “Flying Home,” a jazz number by Lionel Hampton (Ella Fitzgerald would later sing a powerful version) that, for African-American GIs, signified a journey toward the kind of freedom at home they’d been fighting for abroad.

Franklin Roosevelt died of a cerebral hemorrhage on the afternoon of Thursday, April 12, 1945, in his cottage at Warm Springs, Georgia. As the president’s body was being moved to the train for the trip to Washington, a naval chief petty officer, Graham Jackson, tears streaming down his face, played “Going Home” on his accordion.

Woody Guthrie may have offered the most timeless memorial to the fallen Roosevelt. In a song addressed to Eleanor, Guthrie remembered FDR as a providential figure:

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt, don’t hang your head and cry;

His mortal clay is laid away, but his good work fills the sky;

This world was lucky to see him born.

There is, really, nothing more to say on the matter. The world was lucky to see him born.

Jon Meacham is a Pulitzer Prize–winning biographer and author of The Soul of America (2018). Tim McGraw is a Grammy Award-winning country music artist.

From Songs of America: Patriotism, Protest, and the Music That Made a Nation by Jon Meacham & Tim McGraw, published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Merewether LLC and Tim McGraw.

This article is featured in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock Photo.