A Norman Rockwell Myth Debunked

Oh, Pop. My grandfather is 100 percent responsible for this myth — that he couldn’t draw a sexy woman. He said it many times: “I can’t draw a pretty girl, no matter how much I try. I’m afraid that they all look like old men!” One day my father Thomas, his middle son, asked Pop what he meant, and my grandfather explained that he couldn’t draw bodacious, sexy pin-up girls like Vargas and Petty, or even ideally beautiful women like his friend and fellow Post illustrator Coles Phillips, known for his “fadeaway girl.” (Norman Rockwell loved faces with true character in them — either young faces untouched by artifice or guile, or old faces with inerasable histories etched into them; every wrinkle, a story.)

But even a cursory look at Rockwell’s body of work instantly proves my grandfather wrong — he painted pretty, even sexy, women of all ages. Most surprising, I discovered that Pop had a remarkable skill in painting the beauty and allure of women’s legs, particularly the delicate ankles.

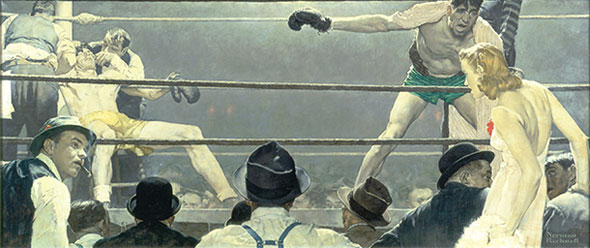

One of my favorite examples of Pop’s most seductive females is the woman in this painting (above). Her stance is like a panther about to pounce. We see mostly her back — a psychologically expressive landscape. This is a woman who will do anything to get her way and takes no prisoners. Classic femme fatale. It’s an illustration for the story “Strictly a Sharpshooter,” by D.D. Beauchamp, who later became a Hollywood screenwriter.

The atmosphere and feeling of the painting is very film noir — the gloomy tones, the smoke, the beleaguered boxer, the tough guy in a fedora with a cigar hanging from his mouth. And, of course, the “dame”: “The dame was an ex-stripper in a cheap burlesque, and she was strictly a sharpshooter. She liked fur coats and champagne, and you didn’t buy those things on the kind of dough you made out of club fights.” Pop’s art always stayed close to the details of a story.

Story illustration for American Magazine, June 1941.

Oil on canvas, 30” x 71”. Norman Rockwell Museum Collections.

© Norman Rockwell Family Agency. All rights reserved.

My grandfather went to a Columbus Circle boxing club to soak up the atmosphere, get a taste and feel for what the ring was really like. He probably used George Bellows’ painting Dempsey and Firpo (1924) as inspiration. Bellows, part of the Ash Can School of artists, was known for his amateur boxing scenes — stark contrast of colors — visceral — muscular — edge and grit. Both Bellows’ and Rockwell’s paintings are done horizontally — the ropes are an important visual that create tension and a sense of imprisonment. Both paintings are dramatically expressive, in the moment. They hint at the light above and play with chiaroscuro, but Bellows’ contrast is more pronounced. Pop’s one error, in my opinion, was comically exaggerating the expression of the boxer. It takes away from the power of the painting. But Rockwell’s also has a marvelous study of fedoras — each one its own character.

Elizabeth (aka Toby) Schaeffer, the wife of one of Pop’s best illustrator friends, Mead Schaeffer, posed as the sexy “sharpshooter.” Gene Pelham, Pop’s photographer in Arlington, Vermont, posed as the tough guy looking at her in disbelief.

When the illustration appeared in American Magazine, June 1941, the bold caption underneath read: “The crowd expected to see a hard-hitting youngster spar with a punch-drunk bum. Instead they saw the battle of the ages — a blue-eyed blonde as the stake.”

So why did my grandfather misstate his skill? My grandfather’s humility was very real, and at times his lack of confidence could be crippling. Perhaps if he sold himself short first, he would beat others to the punch.

Warm wishes as always,

Abigail

———

Strictly a Sharpshooter is part of “American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell,” currently on view at Tampa Museum of Art, Florida. The painting will return to the Norman Rockwell Museum in the summer.