The Five Closest U.S. Presidential Elections

In racing, whether horse or auto or foot, they call it a photo finish. That’s a result that’s so close that it’s almost impossible to discern with the naked eye, necessitating careful examination of a still picture to determine the winner. While you can’t resolve an election with a simple photo, history is loaded with contests that have been, at many points, too close to call. Though the rule of law and an orderly transition have been the norms in the United States since its inception, that’s not to say that arriving at a winner hasn’t on occasion been a rocky or contentious ordeal. With that in mind, here are the five closest presidential elections in the history of the United States.

Before digging in, one acknowledgement that you have to make is that the election is decided by the quirk of all quirks, the electoral college. The electoral college’s votes decide the outcome of the election, regardless of the outcome of the popular votes; though most presidential elections have “matched up” in terms of who won both the popular and electoral majorities, there have been five separate occasions when the “winner” lost the popular vote but was nevertheless conferred the presidency by the electoral college. Since the college is the final arbiter of victory, this list will be concerned with the closet elections in terms of the college; if you’re curious about the five closest in terms of the popular vote, those were: Kennedy over Nixon, 1960 (popular margin of 500,000 votes); Garfield over Hancock, 1880 (7,368 votes); Gore over Bush, 2000 (Gore had 500,000 more votes, but lost via the electoral college); Tilden over Hayes, 1876 (if you’re saying you don’t remember a President Tilden, you’re right; Tilden’s 250,000 more popular votes couldn’t tip Hayes’s electoral victory); and John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson (just wait).

So then, here are the closest presidential elections in terms of the electoral college.

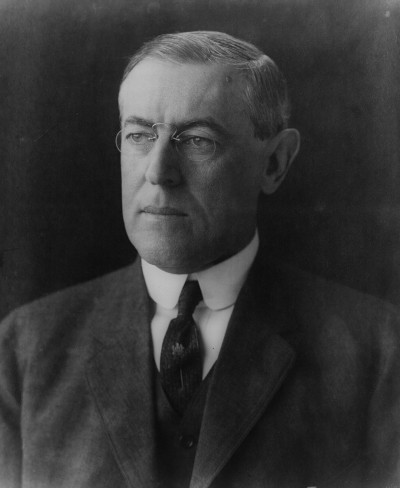

5. Woodrow Wilson vs. Charles Evans Hughes (1916)

Hughes was the former Republican governor of New York and a Supreme Court justice, and Wilson was the incumbent president. Wilson campaigned heavily on the fact that he had thus far kept the U.S. out of World War I. Ultimately, the desire to keep America out of the war proved to be too strong a force for Hughes to overcome. Wilson received 277 electoral votes to Hughes’s 254. In a historic bit of irony, the U.S. was fully immersed in World War I by April of the following year.

4. John Adams vs. Thomas Jefferson (1796)

Adams and Jefferson had a complicated, sometimes fiery, relationship. They were friends in the Continental Congress, served under first president George Washington together (with Adams as vice president and Jefferson as secretary of state), and later became bitter political rivals. Though they eventually mended fences and had years of correspondence with one another before dying on the same day (July 4, 1826), the 1796 election was one of their first heated moments of competition. Washington had the opportunity to run for another (third) term, but opted out. Adams and Jefferson both ran with running mates, but by a quirk of the rules that would later be altered in 1804 by the 12th Amendment, electors of the electoral college could vote for each person separately regardless of running mate, giving Adams 71 votes and Jefferson 68. By the rules as they stood, Adams became president, and his opponent became his vice president.

Honorable Mention: Thomas Jefferson vs. John Adams (1800)

This doesn’t quite count because of its overall strangeness, and it’s a situation that wouldn’t happen again today due to rules updates and the 12th Amendment. In a rematch of 1796, Jefferson and Adams ran against one another. However, this time there were formalized tickets, and Jefferson ran with Aaron Burr, while Adams had Charles Pinckney as his running mate. The rules being what they were, electors could cast votes for the individuals, rather than the ticket, so it ended up that Jefferson and Burr were tied with 73 electoral votes. That led to the election being decided in the House of Representatives, with Alexander Hamilton famously influencing the vote for Jefferson (the events of the election were described, albeit in a somewhat fictionalized manner, in “The Election of 1800” in Hamilton: An American Musical).

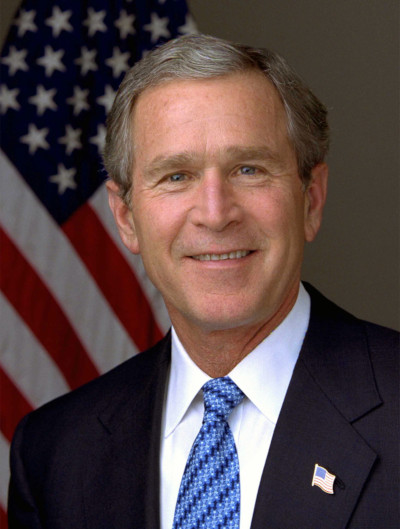

3. George W. Bush vs. Al Gore (2000)

We’ve already established that Gore won the overall popular vote. Of course, it all comes down to the electoral side. At issue was the fate of Florida’s 25 electoral votes, which would be the tipping point for either candidate. Things were so close that Gore called Bush to concede, and then took his concession back. Florida went into a statewide machine recount, as the popular vote would determine the disposition of the electoral vote; Gore also asked for a manual recount in four crucial counties. The Bush campaign sued to stop the recount, which triggered a run of decisions and appeals that went up to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ordered the recount stopped by December 12; at the stoppage, Bush was ahead by 537 votes. Florida’s electoral votes went to Bush, and he became president by a margin of 271 to 266.

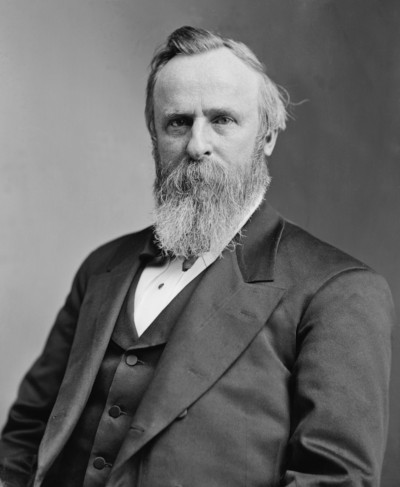

2. Rutherford B. Hayes vs. Samuel Tilden (1876)

This would be the closest election (in fact, the Post once called it the “worst election”) if it weren’t for the unprecedented action that followed in the Number One slot. The initial electoral count showed Tilden ahead of Hayes by a margin of 184 to 165. The 20 votes of Oregon, Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana remained in dispute, with both sides declaring victory. Wheeling and dealing led to an agreement that’s called the Compromise of 1877; the states offered their electoral votes to Hayes if he would essentially end Reconstruction and withdraw remaining Union troops from the South. The deal was struck, and Hayes defeated Tilden by a single electoral vote, 185 to 184.

1. 1824: John Quincy Adams vs. Andrew Jackson

Going into 1824, there were four proper candidates: Secretary of State (and son of John Adams) John Quincy Adams, Tennessee Senator Andrew Jackson, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, and House Speaker from Kentucky, Henry Clay. Vice presidential candidates were voted on separately; in fact, Clay and Jackson would both receive votes in the category. The field of four candidates split the electoral vote; while Jackson initially had the most, he did not have enough for the electoral threshold. The breakdown was Jackson with 99, Adams with 84, Crawford with 41, and Clay with 37. With no majority winner, the decision then went to the House of Representatives, where each state would get one vote agreed upon by their reps. The 12th Amendment limited the field to three, so Clay was out. However, Clay, who hated Jackson, actively worked to get representatives from areas where he earned votes to support Adams. Adams won 13 states, and the presidency; Jackson finished with 7, and Crawford, 4. Jackson was enraged, as he had won the popular vote and the most electoral votes, but still lost. Making matters worse, Adams appointed Clay to secretary of state. Jackson would allege corruption, making it a centerpiece of his campaign; it helped him ride to victory in his rematch with Adams in 1828.

Featured image: andriano.cz / Shutterstock

Comedians in the White House: Our Favorite Jokes by Presidents

“Thanks, folks. I’m here all this term.”

The president of the United State is supposed to represent the people of the country. And since we Americans have a sense of humor that is strong as it is broad, it’s not surprising that presidents can occasionally crack up their audiences.

Here are a few chuckles from our Chief Executives.

John Adams

on the legislature

“In my many years I have come to a conclusion that one useless man is a shame, two is a law firm, and three or more is a congress.”

Abraham Lincoln

of a political foe

“He can compress the most words into the smallest idea of any man I ever met.”

Theodore Roosevelt

on corruption in Congress

“When they call the roll in the Senate, the Senators do not know whether to answer ‘present’ or ‘not guilty.'”

Calvin Coolidge

to a woman sitting next to President Coolidge at a dinner party told him she’d bet a friend she could get at least three words of conversation out of him.

“You lose.”

Franklin Roosevelt

on being informed by an aide that Eleanor Roosevelt (who was conducting a fact-finding tour of a penitentiary) was “in prison.”

“I’m not surprised, but for what?”

John F. Kennedy

“I was almost late here today, but I had a very good taxi driver who brought me through the traffic jam. I was going to give him a very large tip and tell him to vote Democratic and then I remember some advice Senator Green had given me, so I gave him no tip at all and told him to vote Republican.”

Lyndon B. Johnson

addressing a Marine who said, “Mr. President, this is your helicopter over here.”

“They’re all mine, son.”

Jimmy Carter

on a late resurgence of his popularity

“My esteem in this country has gone up substantially. It is very nice now when people wave at me they use all their fingers.”

Ronald Reagan

on other politicians

“I have left orders to be awakened at any time in case of national emergency — even if I’m in a Cabinet meeting.”

Bill Clinton

describing the White House

“Being president is like running a cemetery: you’ve got a lot of people under you and nobody’s listening.”

George W. Bush

“No matter how tough it gets, however, I have no intention of becoming a lame-duck president. Unless, of course, Cheney accidentally shoots me in the leg.”

Barack Obama

on his name

”Many of you know that I got my name, Barack, from my father. What you may not know is Barack is actually Swahili for ‘That One.’ And I got my middle name from somebody who obviously didn’t think I’d ever run for president.”

Donald Trump

on wife Melania Trump’s Republican National Convention speech

“The media is even more biased this year than ever before — ever. You want the proof? Michelle Obama gives a speech and everyone loves it — it’s fantastic. They think she’s absolutely great. My wife, Melania, gives the exact same speech, and people get on her case.”

Featured image: Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and George W. Bush in 2013 (Pete Souza, White House photo)

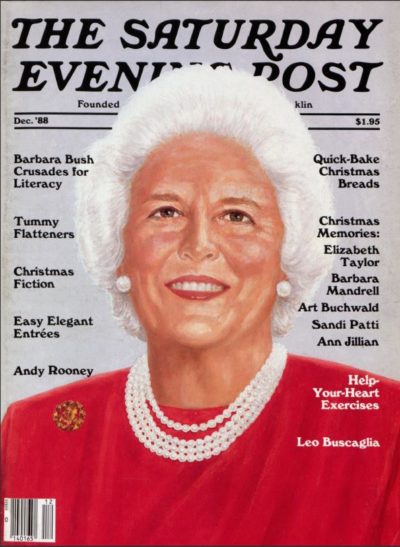

Remembering Barbara Bush

The Saturday Evening Post was saddened to learn of the passing of First Lady Barbara Bush, wife to President George H.W. Bush and mother to George W. Bush.

An illustration of Mrs. Bush graced our December 1988 cover. Inside, we featured a story of her tireless efforts to fight illiteracy. She became involved with literacy when her husband became vice president in 1980, and her efforts and influence grew from there. She endorsed and supported the Project Literacy U.S. campaign, served on the board of Reading Is Fundamental, and convinced the McGraw-Hill CEO to devote his retirement years to literacy. Shortly after this article was published, she launched The Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy.

The story also illustrates many of the qualities that Mrs. Bush was known for: “Warm and unpretentious, she is skilled at putting people at ease, not in a calculating way, but because it is natural for her. She is moved by people and their hopes and fears and joys and problems. Most of all, she is moved by new learners, by their courage and determination.”

11 Facts about Presidents and Approval Ratings

Every day, Gallup Inc. fires up its phone banks and calls hundreds of Americans, asking them their opinions on social and political questions.

One of Gallup’s most closely watched polls is the rating of presidential job approval. Gallup has been conducting this poll continually since 1945. Each week, Gallup workers talk to 3,500 Americans (70 percent on cellphones, 30 percent on landlines) to ask, “Do you approve or disapprove of the way [insert name here] is handling his job as president?”

Journalists, pundits, lobbyists, and politicians await the latest results, eager to spot trends or opportunities in America’s attitude toward its chief executive.

Here are some notable achievements in the field of presidential approval:

1. The Biggest Drop in Approval goes to Harry Truman. When he stepped in to complete President Roosevelt’s term in 1945, Truman had the approval of 87 percent of the country. Six years later, with the Korean War dragging on, rising inflation, unpopular price controls, and southern Democrats feuding with him, his approval had fallen to 22 percent.

2. Most Popular is George W. Bush, who achieved 90 percent approval in the days following the 9/11 attacks. It slipped to 58 percent over the next two years but shot up again, reaching 72 percent when the Iraq invasion was launched. His popularity experienced a long decline in his later years, when his approval rating fell to 29 percent. But then, popularity usually falls during second terms.

3. The Highest Average Approval for an Entire Term in Office goes to John F. Kennedy. On average, his daily approval rating was 70 percent. His popularity rating also shows the fewest sharp rises and falls of approval scores.

4. The Lowest Average Approval belongs to Jimmy Carter, at 47 percent.

5. The Graceful Exit Award: With just two exceptions, every president’s approval rating has dropped in the time between taking and leaving office. Those exceptions are Ronald Reagan (in at 53 percent, out at 63 percent) and Bill Clinton (in at 58 percent, out at 66 percent).

Approval is just half the story. Gallup also counts how many people disapprove of the president.

Note that an approval rating of 40 percent doesn’t mean 60 percent of Americans disapprove of the president. There is usually a buffer of “no opinion” holders.

Some presidents have had low approval scores without correspondingly high disapproval ratings.* For example, when Truman’s approval in the summer of 1950 hit 42 percent, his disapproval score was 32 percent, indicating 25 percent of Americans expressed no opinion. When that margin of grace shrinks, it can indicate fewer Americans are giving the president the benefit of their doubt.

6. The Highest Disapproval Rating goes to George W. Bush, who reached 71 percent.

7. The Lowest Disapproval Rating belongs to Harry Truman. Back when he was enjoying 87 percent approval, his disapproval score was just 2 percent.

8. The Biggest Rise in Disapproval goes to Richard Nixon, who went from 5 percent to 66 percent. Just as presidents’ approval ratings usually drop, every president’s disapproval rating has risen during his time in the White House — just not by this much.

9. The Lowest Approval/Highest Disapproval on Entering Office award goes to Donald Trump. Both scores were 45 percent.

10. The Highest Approval for a President’s First Three Months in Office, As Rated by Voters in His Own Party, is Barack Obama, who earned a 90 percent approval rating from Democratic voters.

The same award for a Republican president goes to George W. Bush; 88 percent of Republican voters gave him early approval.

11. The Most Divided Approval Ratings are for Donald Trump: During Trump’s first quarter as president, Republicans gave him an 87 percent approval; Democrats, 9 percent — a 78-point difference.

Naturally, presidents don’t enjoy high approval ratings from voters in the losing party, so there’s usually a partisan gap in scores.** When narrow, it indicates the president may have potential support from voters in the other party. For example, Dwight Eisenhower’s early approval score was 86 percent among Republicans and 61 percent among Democrats, a difference of only 25 points.

A widening gap reflects a loss of bipartisan support. During his first quarter, Ronald Reagan widened the partisan gap to a 41-point difference. With Clinton, it hit 51; George W. Bush, 61; Barack Obama, 60.

Presidential Approval and Disapproval Ratings

| President | Approval High/Low Scores | Start/End Approval Scores | Overall Average Approval Score | Disapproval Low/High Scores |

Start/End Disapproval Scores | Average Q1 Approval Ratings of President’s Party/Opposition Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Truman | 87/22 | 87/32 | 56 | 2/66 | 2/64 | |

| Eisenhower | 79/48 | 68/59 | 65 | 7/35 | 7/28 | 86/61 |

| Kennedy | 83/56 | 72/58 | 70 | 6/30 | 6/30 | 85/57 |

| Johnson | 79/35 | 78/49 | 55 | 2/52 | 2/37 | |

| Nixon | 67/24 | 59/24 | 49 | 5/66 | 5/66 | 82/50 |

| Ford | 71/37 | 71/53 | 47 | 3/46 | 3/32 | |

| Carter | 75/28 | 66/34 | 46 | 8/57 | 8/55 | 78/54 |

| Reagan | 68/35 | 51/63 | 53 | 13/52 | 13/29 | 83/42 |

| Bush | 89/29 | 58/56 | 61 | 6/59 | 6/37 | 78/41 |

| Clinton | 73/37 | 58/66 | 55 | 20/53 | 20/29 | 78/27 |

| Bush | 90/25 | 57/34 | 49 | 9/71 | 25/61 | 89/31 |

| Obama | 67/40 | 67/59 | 48 | 12/57 | 12/37 | 90/30 |

| Trump (as of 8/16/17) | 45/36 | 45/- | 40 | 47/58 | 45/- | 87/9 |

Article and chart data provided by Gallup, Inc.

*Disapproval data is from The American Presidency Project.

**Political division of voting data is from Huffington Post.

Featured image: Shutterstock

9 Most Scandalous Senate Confirmation Fails

Politics is the usual grounds for rejecting a Cabinet nominee, but candidates have found themselves locked out of the Cabinet for other reasons, including revenge, arrogance, and just plain stupidity.

- Burned bridges. John Tyler made a lot of enemies when he became president. He’d been a member of the Whig party for years but, once in office, he vetoed several bills introduced by his own party. The Whigs responded by kicking him out of the party and rejecting four of his Cabinet nominees. Tyler was so determined to get his treasury secretary confirmed that he nominated him a second and third time on the same day. The senate rejected him all three times.

- Too much sugar. Charles B. Warren was rejected for the Attorney General’s position under Calvin Coolidge because of his ties with the powerful sugar industry. Opponents believed he would not enforce anti-trust laws.

- Bank error. Roger B. Taney was rejected for Treasury Secretary because, at President Andrew Jackson’s orders, he withdrew federal funds from the Second Bank of the United States, which put it out of business. Friends of the bank paid Taney back by rejecting his nomination. (Unfortunately, Jackson appointed Taney to the Supreme Court, where he caused untold trouble with his decision in the Dred Scott case.)

- No vacancy. After Lincoln’s assassination, Andrew Johnson tried to fire Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Johnson nominated Thomas Ewing to replace him, but Stanton refused to leave and the Senate refused to consider Ewing’s nomination.

- Permanent hiatus. When Andrew Johnson was impeached, his Attorney General, Henry Stanbery, resigned his post to defend Johnson. After the impeachment trial ended, Johnson re-nominated Stanbery, but the Senate was still angry with Johnson and wouldn’t let Stanbery resume his old position.

- Taxi evasion. Tom Daschle, President Obama’s choice for Secretary of Health and Human Services, was criticized for problems with unclaimed income on his taxes, mostly related to free access to a limousine and chauffeur.

- Pompous and circumstance. President Eisenhower’s commerce secretary nominee, Lewis Strauss, was disdainful and condescending to the Senate. Moreover, he insisted on cross-examining witnesses and senators who opposed him, which turned even his supporters against him.

- Home maid headache. At least four nominees withdrew when it was learned they had hired undocumented domestic workers:

- Zoe Baird (Clinton’s Attorney General nominee)

- Kimba Wood (Clinton’s second Attorney General nominee)

- Linda Chavez (George W. Bush’s Labor Secretary nominee)

- Bernard Kerik (George W. Bush’s Secretary of Homeland Security nominee)

- Wine, women, and wrong. Nominated by George H.W. Bush for Secretary of Defense in 1989, John Tower’s reputation was tarnished by accusations of heavy drinking and womanizing. Tower admitted he drank excessively, but vowed to quit if accepted. It wasn’t enough to win confirmation. This was the last time the Senate rejected a Cabinet nominee.

In 2013, Senator Harry Reid changed the rules of the confirmation process (the infamous “nuclear option”). Now, nominees only need the approval of a simple majority vote of 51 instead of the previous 60 required to break a filibuster, likely giving President Trump a clear path to confirmation for all of his nominees.

Top 10 Winter Reads

Fiction

The Girl Before

by J.P. Delaney

An enthralling psychological thriller that spins one woman’s seemingly good fortune, and another woman’s mysterious fate, through a maelstrom of duplicity, death, and deception.

Ballantine

The Sleepwalker

by Chris Bohjalian

In this thriller about lies, loss, and buried desire, Annalee Ahlberg is a sleepwalker who goes missing. While she has disappeared in the past, this time seems eerily different, and her children are worried.

Doubleday

Lincoln in the Bardo

Lincoln in the Bardo

by George Saunders

In 1862, Abraham Lincoln lost his 11-year-old son, Willie. The National Book Award winner draws inspiration from this event to write a kaleidoscopic tale that takes place in a single night.

Random House

4 3 2 1

4 3 2 1

by Paul Auster

A child is born two weeks early in 1947. Starting at the maternity ward, Auster explores four separate paths for the child. Inventive yet realistic, this is one of Auster’s greatest works. Perhaps the best.

Henry Holt

The Futures

The Futures

by Anna Pitoniak

Evan and Julia are from widely divergent backgrounds. After they meet at Yale and fall in love, they move to New York, where all is rosy until the 2008 financial collapse hits.

Lee Boudreaux Books

Nonfiction

Thomas Jefferson — Revolutionary

Thomas Jefferson — Revolutionary

by Kevin R. C. Gutzman

Fascinating perspective on a radical founding father. Jefferson had very clear thoughts on citizenship, the size and scope of government, and other important topics of the time that still resonate today.

St. Martin’s Press

The Nature Fix

The Nature Fix

by Florence Williams

We all know that nature is good for us. In this book, the author looks at the intersection of nature, mood, health, and creativity.

W.W. Norton

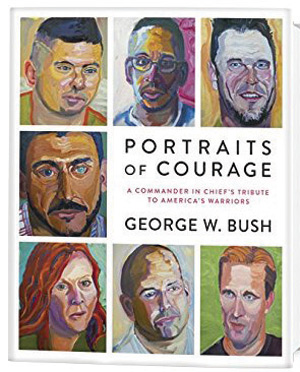

Portraits Of Courage

Portraits Of Courage

by George W. Bush

A vibrant collection of oil paintings and stories honoring the sacrifice and courage of America’s military veterans. Net author proceeds donated to George W. Bush Institute’s Military Service Initiative.

Crown

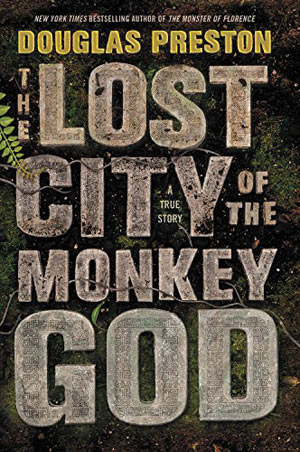

The Lost City of the Monkey God

The Lost City of the Monkey God

by Douglas Preston

In 2012, the best-selling thriller writer boarded a small plane into the Honduran interior to search for a fabled lost city. Here is that story.

Grand Central Publishing

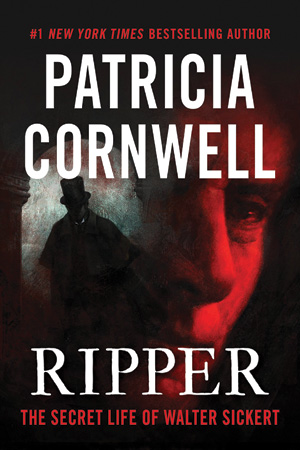

Ripper: The Secret Life of Walter Sickert

Ripper: The Secret Life of Walter Sickert

by Patricia Cornwell

This best-selling author has been on the trail of Jack the Ripper for years. Here, she adds more extensive evidence to her theory that the fabled murderer was a charismatic Victorian painter.

Thomas & Mercer

Obama’s Rockwell

“Celebrate America—Past, Present, and Future.” That’s the tagline of our country’s oldest magazine. The Saturday Evening Post’s legendary archives date back to 1821, but the magazine is better known for its ever-popular cover art and inside illustrations. Artists range from the iconic Norman Rockwell to the lesser-known Western depictions of W.H.D. Koerner.

It’s only fitting, then, that when it comes to selecting art that both reflects our nation’s values and presidents’ personal tastes, the highly revered paintings from The Saturday Evening Post are an appropriate fit, with images that speak to the everyday American spirit.

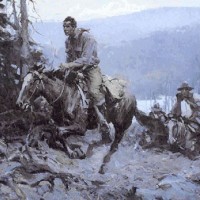

From his governor’s office in Texas, former President George W. Bush brought to the Oval Office a favorite painting of his: a Western scene called A Charge to Keep by W.H.D Koerner. The illustration first appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in 1916 to depict a short story called “The Slipper Tongue.”

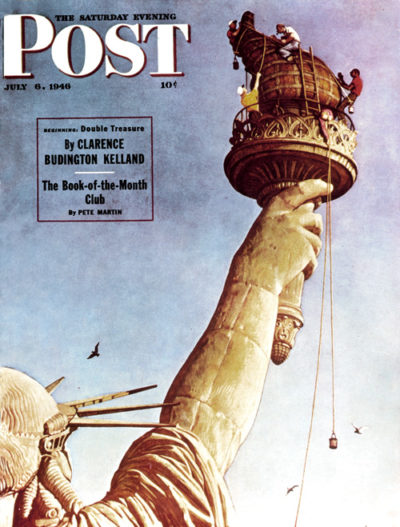

With A Charge to Keep back home in Texas, the Obamas, along with their appointed interior designer Michael Smith, gave the Oval Office a subtle makeover, replacing the cowboyesque décor (with the exception of artist Frederic Remington’s sculpture The Bronco Buster) with a more traditional touch, while embracing such classics as the Norman Rockwell painting, the iconic Working on the Statue of Liberty, which appeared on the cover of the Post in July 1946.

The original work of art was previously owned by famed film director Steven Spielberg—an avid Rockwell collector. In 1994 Spielberg donated the painting to the White House where it has proudly hung for Presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama, according to Jeremy Clowe, manager of media services for the Norman Rockwell Museum. “An additional series of Rockwell works—appropriately titled So You Want to See The President (The Saturday Evening Post story illustration, November 13, 1943)—are also on loan to the White House, and on view in the building’s West Wing,” says Clowe.

The history of the Post is deeply rooted in American culture and will not only continue to find a home in the heart of America, but in the hearts of Americans. Today’s Post readers turn to the magazine for a dose of artistic nostalgia, an update on current cultural trends, and a forecast for medical breakthroughs and emerging technology of days to come, as the Post continues to “Celebrate America—Past, Present, and Future.”