Make Money, Not War

Looking back, America’s entry into World War II seems so inevitable, so necessary you might wonder why we didn’t get involved sooner.

The strongest reasons at the time were that we weren’t being directly threatened and we had no treaties requiring us to defend other countries.

Many Americans personally opposed the war, some for political, others for moral reasons. The Post’s financial reporter Garet Garrett opposed it for practical reasons. The cost of war had become too high. Military conquest in the modern age was simply impractical.

Germany’s attempt to conquer Europe was doomed to fail because conquering countries was a money-losing proposition. Germany didn’t need to spend a fortune to invade France and capture Paris, Garrett argued. It would be less expensive for Hitler to demand a tribute payment from the French without having to occupy the country. The arrangement would be more profitable to both countries.

Even if Germany conquered Europe, how could it make money from these possessions? The citizens of already-conquered Czechoslovakia and Poland would refuse to serve as Germany’s cheap labor. What could the Germans do? They couldn’t threaten foreign workers with death, Garrett wrote, because every Czech or Pole who was executed was “one customer less for the products” of Germany, and the Germans had always complained they didn’t have enough customers.

Germany’s ally in Asia was already making this mistake in China. Japan, he wrote, “has wrecked the economic life of China and killed her own customers by hundreds of thousands. How much buying power have these dead Chinese for Japanese goods?”

Well, not much. Yet Japan didn’t seem bothered to lose thousands of potential consumers. And Germany was preparing to become particularly careless in its treatment of Jewish customers. The business implications seem to have escaped the Nazis.

It hadn’t occurred to Hitler — as it had to Garrett — how senseless any attack on Great Britain would be. Germany “cannot hurt the economic position of England without hurting her own, because in time of peace England had been her best customer. … The web of trade now is such that rivals are one another’s customers.”

His conclusions seem naïve to us; obviously Hitler was continuing the invasions despite the costs. But Garrett had been a financial reporter for 20 years. He was accustomed to seeing the world’s problems in terms of business.

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-001-0285-31A/Rutkowski, Heinz/CC-BY-SA)

He didn’t think he was alone in his conclusions, either. “The voice of business, big and little, has been raised not only against war as a moral evil but against a war boom and war profits as economic evils,” he wrote. “It has neither heart nor stomach for war profits.”

He might have been a bit more skeptical about the attitude of American businesses toward war profits. When orders for armaments began to arrive, manufacturers motivated by profit as well as patriotism readily took up the orders. Between 1939 and 1945, gross profits of American business rose 300 percent, surpassing $20 billion in 1945. Corporate assets rose from $54 billion to $100 billion. (Business wasn’t alone; workers benefitted from the war effort, too. By 1945, the average income was $3,000, over twice its 1939 level.)

But Garrett wasn’t completely wrong. When the war ended, the U.S. ignored the tradition of punishing conquered nations and helped rebuild Germany. Our country recognized the truth in Garrett’s statement: “your enemy is also your customer, and indispensable as such. … You cannot kill a people, neither could you afford to do it if you would. Therefore, all you can do is to help your enemy up, dust him off, straighten his tie, and put money in his pocket in order to begin trading with him again.”

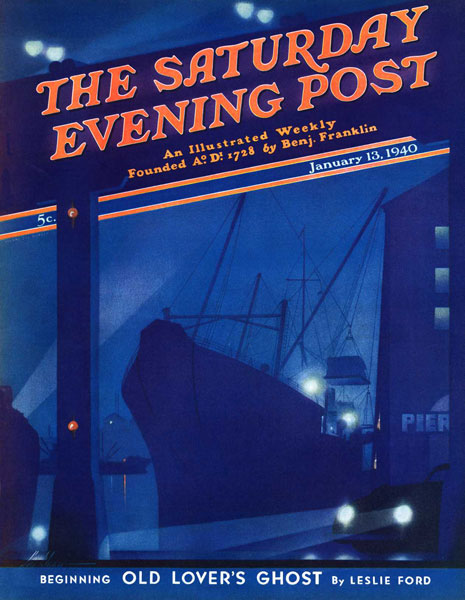

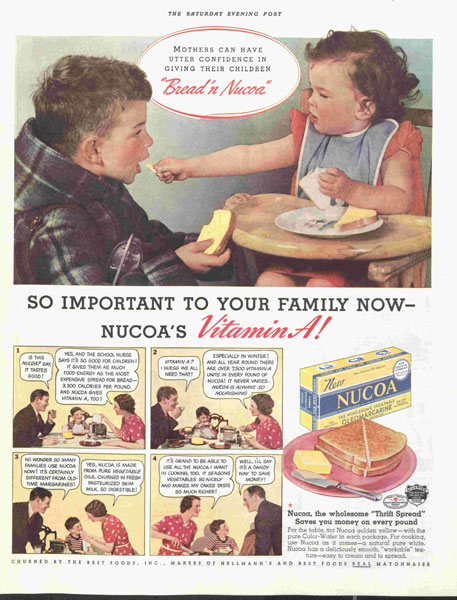

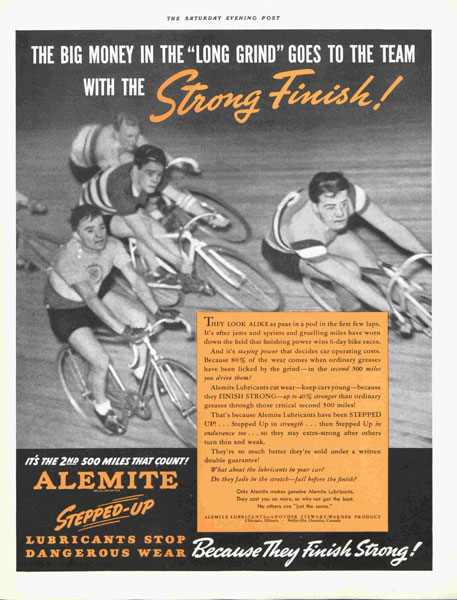

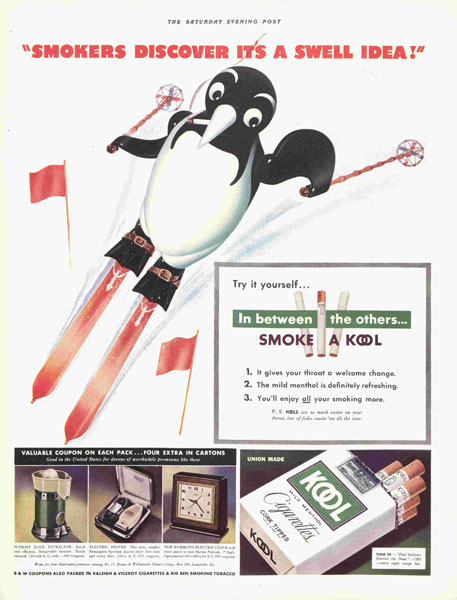

Step into 1940 with a peek at these pages from the January 13, 1940 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, 75 years ago: