Barga

Just a year after my father’s demise, his face, or to say the image of him, started corroding from my memory. Now, after almost a decade, the only memories I’ve left of him are the stories he used to tell every time my brother Nivin and I had a fight. And the times he took us to the woods, as soon as it started drizzling, to hunt for the monitor lizards.

‘Never attempt to catch this guy from up front,’ he used to say, skinning the animal. ‘If it manages to clasp its teeth around your leg, either one of you must die before it would release its grip.’

My father was a man full of fascinating stories. In summer nights, we used to sleep on the veranda to escape the heat and my father would take us from the mysteries of treasure pots to the fables of misty ghosts through the legends of forest–dwellers. Like a perennial stream, until he died, he had never run out of stories. Often, when he repeated a story, I used to point it out and he would narrate the same story in a different but a compelling way. The only problem with his tales was the moral he tried to attach to them as an epilogue. For instance, at the end of his tales about the lizards, he used to say: ‘Hold on to what you love with as much rigor as that lizard.’

I was so captivated by his stories that after my mother’s death, I started accompanying him to the fields and helping him with his chores as he went on narrating his stories one after the other. In that way, I hung around him for most of his life while my brother squirmed at us and roamed about with the goons he called friends.

One day, Nivin approached me as I was assembling the cart. ‘Why don’t you join us, Njani?’ he said. ‘What good it’ll do you loitering around with the old man?’

‘Leave about good for a second. What bad has come out of it that you’re so bothered?’

‘I think it’s high time you hang out with the people your age.’

‘What’s your problem, eh?’

‘Everyone thinks you’re a sissy. Even my friends say that you’re a baby who’s reluctant to get off from his father’s lap. They’re saying it to my face, Njani. It’s ruining my repute.’

‘Now I understand you. That’s what this is all about, then?’

He stormed out of the house stomping and cursing. After that incident, he refused to talk to me for a couple of years after which he grew up and started helping my father in the fields.

Speaking of my brother, the only similarity Nivin and I shared was a birthmark on our thighs. He always hated the fact that we were twins and I came out of my mother first — or at least that’s what the witcher woman told my father. So my father considered me the elder one, to Nivin’s distaste, even though he looked older and taller and thought he was wiser than me.

So he preferred calling me by my name instead of Anna which used to upset my father a great deal. Whenever he heard my brother calling me Njani, he would lose his calm and thrash him with a tamarind stem until my mother interfered. A few times she too couldn’t stop him but would fall prey to his angst.

Growing up, I observed this in several other twins — the younger one of them always looks elder. I tried to convey this to Nivin many times but his head was as thick as his skin.

One day, we were fighting for the deer meat. Nivin wanted a stew made out of it while I preferred roasting it on coals. My father then intervened and narrated this story, I think, to gross us out. He began:

‘Like me, my father, grandfathers, great-grandfathers, and great-great-grandfathers, everyone had only sons as their progeny. Except for my brother who had two daughters — both of them were still-born. Some villagers considered it a boon on our lineage while some, a very few of them, deemed it to be a curse.

‘It was said that one of my grandmothers wanted a girl-child and prayed the mountain gods for years together but it looked like they weren’t kind to her prayers. Still not deterred, in her fifties, she adopted a girl from her distant relatives despite the resistance from both sides of the family. Even though such a thing called adoption was unprecedented in our village up until then, somehow she managed to get her husband’s and the birth mother’s approval.

‘They looked after the baby with their life. The husband brought crabs from the fields, tied a wire to their claws so that the baby could walk them like a dog. When the baby got tired of playing, they fried the crabs on coals and ate their meat. The woman never left her side and was said to have taken the baby along even when she had to pass water. Together, they did everything they could do to keep the baby happy.

‘When the baby was five, the husband brought home a wounded crane from his farm so that the baby could play with it. To his joy, the baby got excited, as soon as it saw the crane, ran to the bird jumping, and started playing with it. The old man, contented on watching the baby’s mirth, went for his daily dose of toddy. The old woman was busy preparing sticks for her cooking while the baby was left alone with the crane in the veranda. The crane might have mistaken the baby’s eyes which were moving rapidly for fish or god-knows-what and tried to have a bite. The old woman heard shrills and rushed to the baby to find her eyes — both of them — gouged out by the crane. An eye was strewn on the floor soaked in blood and the crane was picking at it with its beak. And the other one was dangling on her milky cheeks now turned bloody by the optic nerve. Howling, the woman kicked the bird with all her might. The bird bugled and would have flown away but for its wound.’

There was a strange custom in our village. If anyone’s on the verge of dying or unsure of survival, they rotate a live black hen around their head. They believed that if the hen dies, the person lives and if the bird lives, the person dies. In this case, my father told us, instead of wasting a hen, they thought they could use the culprit crane. It died immediately, but to their shock, the baby died after two days.

Our village priest used to run a school in his backyard, taking in kids under three years and teaching them to write and read until they were of ten years. The only reason my father sent us there was that the priest charged neither money nor grain for his services. Those were the times when the closest thing we’d had to a slate was a fistful of sand filled in a brick stencil and we had to use our forefingers to write on it. Our initial excitement, with which we had rushed to the school, had worn out after an hour into the writing practice. Not a single pupil went home that day without bleeding fingers.

It was worse in my case. While my brother’s skin had just a shear, my fingernail came off entirely leaving me in agony for over a month. My father scampered to the school the next day and abused the priest with such a harsh tongue that it compelled the poor fellow to provide finger caps made of cloth from then on. Even after that consolation, my father was hesitant to send me back. But somehow Nivin convinced our mother and continued his classes nonetheless. Two years into Nivin’s education, the priest died in a farming accident — he was unloading his cart of rice bags when they fell on him — and the school was closed, for, as it turned out, his sons and daughters were as ignorant as the village folks.

It’s a fact that everyone has love-and-hate relation with their families. But as for me, I had nothing but love for my father and reserved the antithetical for Nivin. At thirteen, he could carry a plow to the field all by himself while I couldn’t even lift it off the ground. Even though we were married to the girls from the same house, Nivin managed to garner more dowry than me. To add to my vacillations, he made it a custom to remind me of my setbacks from time to time. Like when he used to go to school and boast about it, saying that he would grow up to be a learned man while I would turn a ruffian. For quite some time, I tried to bottle my angst and stopped talking to him altogether when I couldn’t take it anymore.

One day as I was leaving for the weekly market, my father called for me.

‘Njani, why don’t you call for your brother so that we could have a chat?’ he said snuffing his naswar.

I remained silent, upon which he replied: ‘Is there something wrong between you both?’

I shrugged my shoulders. He continued nonetheless: ‘Do you care for a story, Njani?’

‘This isn’t the time, Bapu,’ I began, ‘I am leaving for the market — ’

‘Sit down,’ he cut me off and began his story before I could even sit.

‘The relation between my father and his brother, my uncle, was worse than the two of youse. It was worse than enmity, you can say. Whenever there was an occasion in the family, dealing with these brothers was a more daunting task to our relatives than making preparations for the event, for inviting one would upset the other. In functions they both had to attend, they cursed at each other, forgetting and foregoing their dignity. I saw them both swearing to kill one another and describe in detail how horridly one would kill the other. Want to know the reason for their hatred?

‘My grandfather had no property besides his agricultural land. So, on his deathbed, he distributed it equally between the brothers, and passed away. Everything was calm until the start of the cropping season. No one in the family knew then there was a storm in store for them — a storm which would last two decades. My uncle accused my father of encroachment on his land. To be honest, my father did no such thing. So, the family stood behind him and my uncle went to the village heads.

‘My father being a sincere man, and they knowing it, the village heads denied to call for a meeting at first. Not dejected, my uncle bribed some of them and made them call my father for the meeting. It went on for a month and my uncle, to bear the expenses of the village heads, had to sell a part of his land. And at the end of it, they decreed that my father was not guilty and there was no such encroachment as accused.

‘Unable to digest the truth and defeat, my uncle, who had a bad taste for them, next sought the help of a revenue officer who lodged a complaint against my father. The case went on for years in the mandal court all the while my uncle’s family starved. His wife died of cholera so he married again and that woman eloped with some bloke just after a year. His children died malnourished while my uncle was busy in the mandal. My dad worked hard on his field, managed his duties and did everything at his disposal to increase the produce on the crop every year. My father was relieved of the case not until you were born, and the verdict was in his favor. As to my uncle, no one knows what happened to him. Some say he committed suicide. Others say they’ve seen him begging in the Barangaon city. We’ve never been there so we don’t know the amount of truth in that news.’

As he completed his story, I looked at him puzzled as to why he narrated it to me.

‘I know how you feel about your brother.’

I opened my mouth but he waved his hand to dismiss my trial of protest. ‘I’m thinking of transferring the land to both of you, this year. You’re old and ready enough, I think. And let me say you this. We don’t worship mythical heroes or gods in our village, Njani. All that we villagers, look upon as success is the highest amount of produce on a crop in a season. I think you can beat your brother at that, don’t you?’

I nodded half-heartedly.

‘And take this as my advice. Never waste your money on pleasures. Do you know the reason they respect me in the village?’

I shook my head.

‘My father, dying, gave me half an acre of land. I bought out the surrounding lands of it and augmented it into two acres. I can say with a bit of pride that I was the only one who managed to do that in my generation. No matter how weak and feeble you are in your childhood, how insecure you are about your strengths, people will forget them once you’re successful in their eyes. That’s the reason, in folklore, heroes are said to have been born with golden armor and wicked people are said to have been born killing their mothers.’

My old man died a year after we’d had that conversation. As promised, he gave both of us an acre of land. And thus began my trials to shellac my brother. The first year, I tried every trick in the book to produce more grain than Nivin. I spent most of my days in the field, took my meals there and drank water from the stream flowing nearby and slept in the meadows for the fear of wild boars.

But all in vain, for at the end of the season, Nivin had managed to turn out the same amount of grain as I. To be upright, he managed a bagful excess, but he donated it to the local deity. So, in a way, we were on the same level in terms of yield.

I worked harder the next year but again it was Nivin who had the upper hand. I would’ve gone mad if not for my wife, who blessed me with a boy snatching away my distress. The year after that, Nivin’s grain weighed two times more than mine. It was then that my wife told me: ‘I think your brother’s cheating you.’

How?, I wondered.

‘He might be stealing from your heaps of grain. Otherwise, think of it, how can he produce more than you without working as hard as you? Listen to me and appoint someone to guard the crop at nights.’

I took heed and selected her brother for the watch-guard. But he reported every morning that there was no such foul play as we feared. Yet I paid him to guard for the entire season. This time Nivin produced the highest grain in the village and people began talking about him. I was so upset that I couldn’t eat food for a week.

Just when everything was going downhill, there came a stranger in our village. He built a shack for himself on the river bank. The entire village took him for a sorcerer and dreaded running into him. People chided when someone brought up his topic, but talk they did of him nonetheless. They were even reluctant, my wife told me one evening, to go to the river to bathe.

Intrigued, I decided to pay a visit to this enigmatic person and went to the river one fine morning. The shack was empty except for a bed and some earthly pots blackened by soot. From the window, I could see the man standing in the river and folding his hands at the rising sun. Sunlight glinted in the drops of water falling from his palms. The wind made his long jet black hair dance to its tune. The scenery was so serene that for a second I forgot all my woes and wanted to join him in the water. He came in as he completed his respects and I took a good look at him. He had broad shoulders, a divine face and looked no more than forty.

After a brief introduction, we began talking, and before I could realize, we talked into the nick of the night. I left unwillingly but returned the next day first thing in the morning. I connoted all my problems to him and he said he would help me. All that I had to do was to believe in his god and pray to Him seven times a day. I did it with unperturbed conviction for a month when he gave me a root wrapped in a leaf. ‘Dip this in your blood and throw it in your field,’ he advised and I abided. Surprisingly, that season, my production increased and was equal to that of Nivin. That cleared any doubts I had had for my friend. And from then on, I started blindly following his words.

The main reason I have trusted him was he never asked for money, grain or a favor. One time when I offered him money, he shook his head smiling and said: ‘I’m here to help you, Njani. And I’m not a man of apprehensions, mind you. When I need a help from you, I’ll definitely ask for it. You can be sure of it.’

The next year, Nivin, had a heavy loss and had to sell a part of his land to clear his debts. I was overjoyed on hearing this but soon it morphed into pity for my brother. I asked him to seek my friend’s help but he was, as always, resistant to counsel.

Even my produce hit an all-time low one season. When I sought for my friend’s aid, he introduced his brother, who looked just like him but only younger. He guided me to change my name by adding a consonant to it. So I changed it to Njanni but there was no change in my produce.

I confronted the brothers seething with anger, when they said in unison: ‘Give us a last chance.’ I did and they asked me to remove a room in my house. I went along with their whims despite my wife’s rebuffs. But at the end of the year, I got the highest grain not only in the village but the entire mandal. As per the custom, the villagers made me a member of the grain board, awarded me two quintals of wheat and gold-coated tiger claws. Somehow the villagers got a whiff of my secret and one by one they thronged to the shack. I never saw the shack empty again. My friend got so occupied with the villagers that I had to send a note asking for a rendezvous which he rejected.

After a month, as I sobered from my success, my friend paid a visit to my house along with his brother and a village head in tow. ‘As for the services we rendered, Njani, we want to charge you a fee,’ he said standing in my veranda. ‘Even though it won’t be sufficed, I would like to have your acre of land.’

Before I could utter a word, he continued: ‘As for my brother, he would have the grain you produced this year.’

I was knocked out of my wits and words failed me. My wife rushed out of the house and started shouting at the edge of her voice, hurling curses at the trinity. Soon, the whole village was standing in our veranda with pricked ears and piqued interests. My friend jotted down the conversations I had with him over the years; only he called them dealings. I was partly relieved that he didn’t reveal my feelings towards my brother. Not one soul spoke up in my defense and it was pretty evident that they were all under his spell. Thus, I was robbed off my land, grain and dignity. The next day my wife left me along with my sons.

A few sympathizers dropped in on their way to the fields the next day to say that they would stand by me. Together we went to the river bank, in hopes of demanding justice, but there was no sign of a shack. Apparently the brothers were wanderers and had left for another village in search of a different friend. On enquiry, I got to know that they sold my land to the village head that was with them on that fateful day.

To my surprise my brother came for my rescue and was ready to give me a part of his land. I didn’t want to live at someone’s mercy, least of all his. So I started working as a laborer in my own field. I waited for my day. After all, my father used to say, every dog has its day. It came after two years, on my trip to a nearby hamlet, where I heard people talking about two brothers with powers in hushed tones. But by the time I had reached them, they had fled. So, I had set out on an expedition asking the wayfarers if they’d seen two identical people in saffron clothes. I lived on wild berries, stream water and slept on the tree branches. I begged, robbed and threatened the travelers for food.

When I had run out of money, I started working in a roadside inn where my friends, on one of their escapades, chanced upon me. They tried their best to slip but I was too slick, by then, for them to escape. I bid a goodbye to my inn-mates and directed my friends to a groove.

‘I know you are cheats. But tell me this,’ I asked them at knife-point. ‘Do you people really have powers?’

‘Would you be standing there threatening us if so?’

‘Then how did you increase my produce every year?’

‘Who told you it increased? It was just higher than everyone else’s.’

As Njani was busy writing his story, a young man in saffron clothes entered his room silently. ‘Swami,’ he bowed down, ‘the other masters are waiting for you.’

‘In a minute,’ Njani said, closing his book, and went for his friends but only after donning a saffron shawl around his shoulders and a smile across his face.

Featured image: “The City of Masulipatam,” 1672, from Columbia University

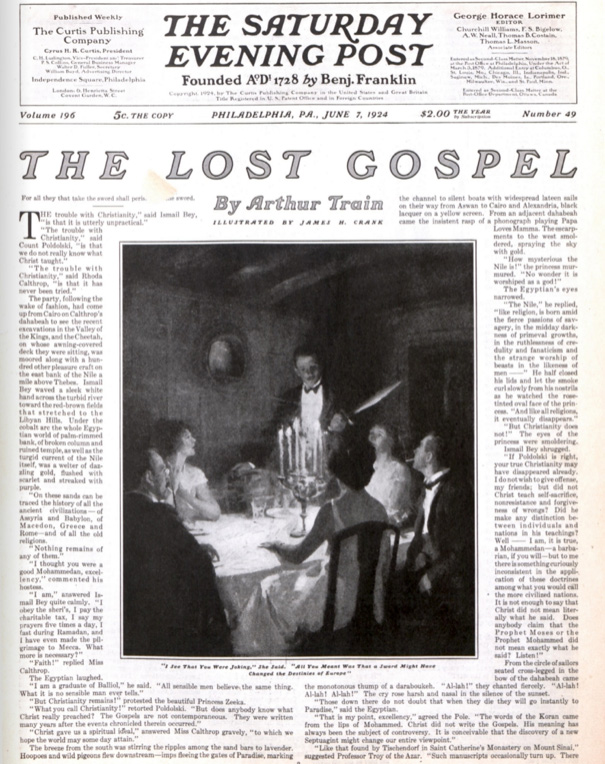

“Here Comes the Bribe” by Sam Hellman

A newspaper reporter and fiction writer with a healthy sense of self-deprecation, Sam Hellman wrote in 1925 that “those who have been reading my stuff will hardly believe that I am a college graduate with an early academic penchant for Greek accusatives and Latin gerundives.” In his humorous stories, witty commoners with crude dialect dress each other down in farcical situations. In spite of his highbrow studies, Hellman observed people and their language while traveling the country after college. In “Here Comes the Bribe,” a scrappy Long Islander accidentally finds success in politics.

Published on April 5, 1924

Politics, I has heard said or read, makes beds strange fellers. Many a true word is spoken of a pest. Ever since I let them Doughmorons fluke me into grabbing off that job in the legislature I ain’t had no more sleep than a guy with the hives doing a six-day bike trick on the corrugated roof of a boiler factory.

Ordinarily a new cuckoo elected from Long Island to one of them per-dime grafts attracts about as much attention out in the state as the second vice president of the Lotto Club of Gimme, Utah, would in Somewhere, east of Suez; but in my cases things is different. Besides being the only Democrat that ever copped in the county, the platform I run on was woozy enough to make the big city papers throw a mess of infernal triangles offa the front page to get room for spelling my name wrong, and also for surprising me with reporters’ ideas of what I would ’a’ maybe said if they’d seen me.

You lads that cuts your breakfast short every Thursday morning and rushes mad to the news stand with a nickel in your hand remembers how Luke Cravens, the boss of the party, slicked me into getting on the ticket with a promise that they was no chance of winning, but a good one of getting the bum’s rush outta Doughmore, which, as more than two million and a quarter folks knows, has been the heights of my ambitions from the day the frau and the Magruders f.o.b.’d me into this limousine layout.

I guess it ain’t fair to blame what happened on Luke, him not having no way of knowing that the Republican bird was gonna beat it with a frill and the building-and-loan jack the day before the election; but I don’t see where I could ’a’ done anymore. It looked like a cinch that I’d be trimmed bad, and besides would get the air from the club crowd on account of the bill I was talking about introducing to slap a heavy tax on golf balls, sticks, links and such.

Instead, here I is with a Hon. stuck in front of my monniker and stronger’n ever with the pill pushers, them blah boys having figured out that what I was aiming at was a deep schemes to keep the rough-raffs outta the game.

After election night I don’t get to see Cravens for a week. Finally, I drifts into the village to give my sorrows swimming lessons and I meets up with him.

“Heard the latest?” I inquires.

“Not lately,” he comes back. “What’s yours?”

“I’m resigning,” I tells him.

“I know one better than that,” says Luke. “They was once a Scotchman and — ”

“I’m resigning,” I repeats.

“Sure you are,” returns Cravens. “Talking about something in general, what’s your ideas on nothing in particular?”

“What do you think I am?” I yelps. “Kidding or cuckoo?”

“If you ain’t serious,” says Luke, “you’re kidding; if you is, you’re what comes after the ‘or.’ What’s eating you?”

“I’m all et,” I answers. “Got any notion what I been through since last Tuesday?”

“Better’n you have,” says Cravens, prompt. “The boys has been running you ragged for cuts of the cake they expects you’ll get for ’em in Albany. In facts, I sent a dozen or so lads up to see you myselfs.”

“That’s damn nice of you,” I barks, grateful, “and I’ll set you up to a quart of wood alcohol the first chance I gets. You responsible for them bobos that drug me outta the hay at three a.m. and them janes — ”

“Janes?” says Luke. “What janes?”

“Well,” I tells him, “I don’t remember the names of more than two or four hundred of ‘em, but they was one old gal that wanted to know where I stood, if anywheres, on Sunday shows; another that tried to smoke me out — ”

“Don’t let them worry you,” cuts in Cravens. “That gang usually gets after the candidates before the election; but not figuring you for a chance, they laid off until right now.”

“They ain’t no ‘right now’ in them cases,” I growls. “It’s wrong whenever.”

“You gotta put up with that kinda stuff,” says Luke. “You must remember you is in the public eye.”

“Yeh,” I comes back, “like a cinder. Can you resign with a lead pencil or do you gotta do it with ink?”

“Forget it!” snaps Cravens. “Don’t be a scoffjob. They ain’t a politician in the state that’s sitting prettier than you is. In a coupla years we’ll have you in Congress, and you might be governor someday.”

“Uh-huh,” says I; “and I might also get to be the mother of the late queen of Armenia, but I ain’t got none of them kinda itches. I’d sooner sleep tight than be President. Anyways, after what I has been doing since I seen you last, I just gotta get out from under.”

“What you been doing?” inquires Luke.

“Nothing,” I answers, “excepting to kid everybody that come to see me into believing that I was wild about the hop they was whooping it up for. I shooed out four women with a cross-my-heart that I’d have the law on the sun for making cider cheat. If that don’t annoy you none, what do you think of the eleven boys I promised the same job to?”

“What job’s that?” asks Cravens.

“Road overseer,” I tells him.

“Don’t worry about that,” says Luke. “It ain’t even vacant. I thought you told me you didn’t know nothing about politics.”

“I don’t and I won’t,” I answers.

“You plays it perfect,” comes back the County chairman. “Promise ’em everything; deliver only to them that does.”

“Does what?” I bites.

“Delivers,” says Cravens. “When do you grab the night boat for Albany?”

“When’d you lose your ear sight?” I yelps. “Ain’t I just got done telling you that — ”

“Now, now,” interrupts Luke, soft, “be mother’s little angel pet. You can’t quit, Dink. We ain’t never elected a Democrat here before, and if you does a yellow we’ll never have another. You can’t expect every Republican to play ball for us by jumping the works with a skirt and the roll. Besides, I thought you was wild about getting away from Doughmore. Here’s a chance to leave it flat for three months, anyways.”

“That part of it’s all right,” says I; “but I ain’t keen about making no sucker outta myselfs. Here I is promised all up to vote nine different ways on everything, from getting after the Pullman folks on this berth-control proposition some wren talked my arm off about, to taking snipes outta little gal’s mouths — ”

“Listen, bo,” cuts in Cravens, “they is only one way of making a sucker outta yourself at the legislature.”

“How?” I asks.

“By going to the mat for something on the account of a campaign pledge,” explains Luke. “It ain’t even good form to mention ’em after election.”

“Ain’t I supposed to act like the voters wants?” I inquires. “Or is I supposed to do like I thinks personal?”

“Thinking’s even rude,” replies Cravens; “but they is two ideas about the subject you brung up. Some holds that a guy should do like he wants to do — ”

“And the other?” I butts in.

“And the other,” goes on Luke, “that he shouldn’t never do nothing that he don’t want to.”

“Smelligent,” says I. “Where does the people get off in that kinda misdeal?”

“They don’t,” answers Cravens. “They keeps right on riding and paying fare.”

II

If it wasn’t for the Magruders I would ’a’ passed up the job in spite of all that Luke said and done to skid me into it, but them babies is got a way of rubbing my fuzz the wrong way and making me do a lotta tricks I shouldn’t oughta. All Jim and Liz has to do is to be for a thing for me to pick up a club and beat its brains in. I ain’t ordered ham and eggs since I found out they liked ’em.

After I finishes up my talk with Cravens, in the which I promised to think it over a couple days, I beats it home and finds the Magruders cluttering up the front porch.

“Has you resigned?” asks Lizzie.

“Want me to?” I comes back.

“Jim says,” answers the measle, “that you — ”

“Never mind what Jim says,” I cuts in. “Ain’t you got no ideas in your own name? Don’t you ever get anything in the box score excepting assists?”

“I got a mind of my own,” snaps the Magruder nix.

“All right,” I admits; “but why don’t you take it outta the safety deposit and show it to us sometime? I ain’t gonna swipe it.”

“I wouldn’t trust a politician,” says Lizzie, cold; “not even with nothing.”

“Is you really gonna take the job?” butts in Jim, quick, to cover up his wife’s fox paws.

“Why not?” I inquires.

“Well,” says he, “it’s a pretty dirty game, ain’t it?”

“Ever play in it?” I wants to know.

“I wouldn’t touch it with a six-foot pole,” he comes back. “They ain’t nobody in politics but a lotta grafters.”

“We once lived in a house,” says I, “where we had a furnace that was always on the bum. One day it got so cold I went downstairs to see what the hell. I found out the janitor was peddling the coal I’d bought and hadn’t taken the ashes out for a month. So I canned him, cleaned the thing out myself and never did have no trouble after that.”

“You should oughta get the kinda furnace we is got,” remarks Lizzie. “Jim says — ”

“The furnace I’m talking about,” I continues, “is a figure in speech.”

“Ours is a Little Diamond Hot Box, ain’t it, Jim?” inquires the sciatica.

“Where’d Lizzie go?” I asks, acting kinda surprised.

“I’m here,” she answers, wide-eyed.

“You’re here, all right,” says I; “but you ain’t there. What I was trying to broadcast,” I goes on, turning to Magruder, “before that frau of yourn turned on the statics, was the idea that if you don’t like dirt you can’t cuss it outta the room; you gotta grab a broom and sweep.”

“I suppose,” sneers Jim, “you’re gonna make politics as clean as a hind tooth, huh?”

“I’ll maybe try,” I answers. “What’ll you do? Stand around while some dip frisks your pockets and bawl out the coppers instead of taking a crack at the crook?”

“Jim ain’t afraid of nothing,” says Lizzie.

“I ain’t afraid of my wife neither,” I shoots back.

“You calling me nothing?” busts out the misses, who ain’t said a word so far.

“Not a thing,” I returns, hasty. “You vote at the last election, Jim?”

“What for?” he comes back. “They don’t count ’em anyways.”

“Well,” says I, “it’s a cinch they don’t count them that ain’t cast. When I gets to Albany — ”

“So you’re going?” interrupts Magruder.

“Yeh,” I tells him. “I kinda feels that I owes that much to prosperity. I’m looking ahead to the time when Dink O’Day Day will be celebrated from Rock Bound, Maine, to Climate, California, and when statutes of me in the parks will be as thick as empty shoe boxes after a church picnic.”

“You’ll look swell in the legislature,” sarcastics Jim. “What do you know about parlor-mantel law?”

“No more’n I know about kitchen-sink law,” I admits; “but it won’t take me more’n a minute and a half to run it down and make it drop from exhaustion.”

“I never seen a guy hate his wife’s husband like you does,” says Magruder. “Ever hear of Roberts’ Rules and Orders?”

“I don’t wear no man’s collars,” I answers, “and that bird Roberts ain’t gonna give me no orders. Anyways, Luke Cravens is the boss of the district. Where does this Roberts boy — ”

“You wouldn’t understand,” cuts in Magruder, “even if you knew. For example, suppose you was to get on the floor of the house — ”

“Who’s gonna put me there?” I yelps. I don’t want you to get no ideas I’m such a stupe as I sounds, but I’m even willing to carry that reputation for the pleasures of razz-jazzing Magruder.

“I mean,” he explains, “if you was making a speech on some bill and a bobo should get up and move that it should be put on the table, what would you do?”

“It all depends,” I answers, “on the way he said it. If he was nice and polite, I’d put it there; but if he tried to rough-bluff me into doing it, I’d leave it just where it was and he’d probably spend the next few minutes picking a inkwell outta his hair.”

“Flying codfish!” hollers Jim, waving his hands like a yell leader. “And you’re the kinda guy that’s gonna make laws for fifteen million people!”

“That’s what,” says I; “but what do you expects if right thinkers like you won’t take no interest in politics and’d rather play golf than vote?”

“Talking about golf,” comes back Magruder, “is you really gonna introduce that tax bill?”

“I’ll tell the popeyed world I am,” I replies. “A dollar on each ball and five fish on each club.”

“Think you can put over a grab like that?” he asks.

“I wouldn’t be so surprised,” I answers. “When I gets done telling the boys about the terrible housing conditions of the ducks on Long Island on account of the land being drug out from under ’em for golf courses, I expects the tax’ll go with one big sob. D’you know things is so bad on the North Shore that seven and eight ducks is gotta sleep on one rock?”

“I didn’t even know ducks slept on rocks,” remarks Lizzie.

“You should study national science, gal,” I returns. “What’d you suppose they slept on? Credit? Where’d you imagine the expression ‘duck on the rock’ come from?”

“I don’t know,” says she.

“I don’t know the name of the saloon neither,” cuts in Kate, slipping me the glare to sidetrack. “Please stop teasing Lizzie and try and give a imitation of talking sense.”

“Who should I imitate?” I inquires. “Jim?”

“You couldn’t go further and do worse,” suggests the Magruder exposed nerve; and when I starts laughing she goes on, all flustered, “I means, you could go further and do no worse.”

“That’ll be enough,” yelps Jim. “I’ll do my own answering back from now and on. Cutting the kidding cold,” he continues, turning to me, “I thought that golf-tax idea of yourn was to keep the cheap johns from building links around Doughmore and the other swell clubs.”

“Even a natural error like you,” says I, “couldn’t be no wronger. Can you see me pulling chestnuts at a fire for the plutocats around here? I’m a friend of the common people and — ”

“The commoner, the friendlier,” interrupts the frau.

“Maybe,” I admits; “but I promised the duck growers of this district that I’d go to the front for ’em, and a promise and a performance with Dink O’Day is as alike as two peas in a puddle. Experts has tried with instruments and them slow movie cameras to find a difference between ’em, but without no luck. It was funny. Oncet they was studying a promise of mine, and when I told ’em after a coupla hours it was really a regular performance and not no promise a-tall, they just gave up.”

“Doing business with a politician,” remarks Magruder, “I guess they hadda. When you gets to Albany them experts’ll be able to leave their naked eyes at home and still see the difference.”

“What makes you think so?” I inquires.

“Didn’t I hear you tell that Glumph woman you was gonna pass a law to stop all picture shows on Sunday, Wednesday and the nights the Ladies’ Aid met?” asks Jim.

“You did,” I tells him.

“Yeh,” jeers Magruder; “and wasn’t I there when you promised Mildew down at the Tivoli that you’d put the censors on the hummer and fix it so the film folks could do anything they wanted to, within reason and without?”

“Such is the case and the facts in it,” I confesses. “What about it?”

“How you gonna keep both promises?” demands Jim.

“What,” says I, “leaving out present company, could be simpler? I’ll introduce the bill the Glumph frill wants and also the one Mildew’s after.”

“How,” yelps Magruder, “can you be on both sides at oncet?”

“Ah,” I returns, “that’s what makes politics a art. What’s wrong with the way I’m doing? Some of the folks in the county wants this; some others don’t want that. Who’m I to say what’s proper for ’em? I’m just like a waiter in a restaurant. Everybody that comes in asks for something different. I puts in the order. If the chef don’t wanna cook up the mess, whose fault is it? A jane drifts in with her trap all set for a pair of fried wizzle-wumph eggs, sunny side up. Is it my business to tell her they ain’t good for her complexions and try and set her up to a platter of raw ox ears?”

“You mean rare, don’t you?” inquires Lizzie.

“I don’t know no more what you’re talking about than you do,” says Jim; “but how you gonna vote on these different things when its comes to a show-down?”

“O’Day,” I replies, “is far enough down on the roll call for my judgment and my conscience to get together before I has to. I’m gonna introduce everything that anyone wants and let ’em take their chances. Personally, nothing don’t interest me excepting my duck bill, and I shall fight for it with all the powers I has, with faith in the right and — ”

“Oh, hire a hall!” snaps Magruder.

“The Monday Club’s got a dandy place,” says Lizzie. “You can get it for fifty dollars a night; besides, they is still got the decorations up from the Pappa Eta Motza sorority dance.”

III

Me and Cravens goes to Albany together, Luke figuring on introducing me around to the high moguls of the party and seeing that I get started off K.O.

“You’ll be kinda busy getting settled,” says he, “so I has taken a little work off your hands.”

“What work?” I asks.

“Well,” he answers, “I figures they is about eight jobs you’ll get to hand to the boys in the district and I’ve picked ’em for you. Seeing as I got you into this, the leastest I can do is to save you from being bothered. I has even notified the lads we’s named.”

“That’s nice,” says I; “but — ”

“’S all right, Dink,” cuts in Luke. “They ain’t no thanks necessary. It’s maybe taken up some of my time and all that; but when I likes a guy, going to trouble for him’s a pleasure.”

“Yeh,” I returns; “but how about them fifty or sixty birds I promised plums to?”

“Albany,” answers Cravens, prompt, “is quite a town. They is a coupla good hotels, and I knows a restaurant I’ll take you to, where you orders tea and gets what you meant.”

Not caring nothing about them jobs at Doughmore, I don’t chase the subject no further. Anyways, I don’t aim to stay long. My ideas is to stick around the legislature just enough to see what makes the thing tick and maybe pull a stunt or two that’ll get me in bad with the jokes at home, after which me and politics’ll call it a day.

Luke makes me acquainted with a bunch of bobos that is supposed to run the works and winds up by taking me to the mansion to meet the governor. He turns out to be a decent feller.

“I has heard a lot about you,” says he to me.

“I’ve seen your name mentioned, too,” I comes back, not to be undone in courtesies.

“I wanna talk to you someday about taxes,” he goes on. “I understands you has studied ’em deep.”

“Governor,” I replies, “I don’t wanna brag, but if they is anything about taxes I don’t know it musta been sprung the day after tomorrow.”

“That’s fine,” smiles the big chief. “They is causing us a lotta trouble. ‘

“Unwrinkle your brow, gov,” I cuts in. “My golf bill will solve everything.”

“I must look into it,” says he, and me and Cravens beats it.

“I thought,” remarks Luke, “that you canned that tax idea of yourn when the Doughmorons started being for it.”

“No,” I tells him, “I’m going through with it just to prove to them coupon barbers that they give me the wrong rap.”

“Well,” says Cravens, looking at me kinda narrow, “the play might work out good for you at that.”

“You mean,” I asks, “the bill might pass?”

“It’s got as much chance of doing that,” he answers, “as one of them ducks of yourn would have in a scrap with three wildcats, four hyenas and a pair of Australian gluffaws.”

“I don’t get you,” I returns, puzzled.

“No?” smiles Luke. “All right, Rollo, roll your own hoop. If you should want me to cut in later on, you knows where to find me.”

I’m still all up in the air trying to figure out what Cravens’s been driving at when I gets to the hotel by myselfs and runs into Shem Conover, a baby from up in the state that was knocked down to me earlier in the day as a real slicker in jamming stuff through the House.

“I been waiting to see you,” says he. “I wanna little chin-chin.”

“About which?” I inquires.

“That golf-tax bill you’re touting,” he answers. “Need any help?”

“I ain’t so sure I’m going through with it,” I tells him, not liking the bimbo’s looks.

“Who’s been talking to you?” he asks, slipping me the narrow eye like Cravens done.

“What you getting at?” I yelps, getting kinda peeved at the mystery stuff.

“Listen, bo,” says Conover, “and don’t try and gruff me off the lay. If you wanna get any action with that bill of yourn you gotta be sweet to me. I’m chairman of the committee that’s gonna get it, and if you don’t put me in the line-up — ”

“What’ll you do?” I barks.

“I’ll fix it,” he comes back, slow, “so that the chloroform won’t work when you want it to, and when you gets ready to deliver the body you’ll find the livest corpse you ever seen.’

“I’ll sue the Central for this,” says I. “When a lad buys a ducat for Albany they ain’t got no right to dump him off at Matteawan.”

“You’re in Albany, little one,” remarks Conover, cold; “and when you is in Albany you gotta do like the Albanians does. Do I get a hand dealt me?”

“I ain’t gonna introduce the bill,” I growls, “and besides — ”

“Too late,” interrupts Shem. “If you run out on it I’ll have it introduced as a committee measure. The idea’s too cushy to drop. They worked it with patent medicine down in Arkansas and with baking powder out in Missouri, but the golf act’s a new one on the sandbag circuit. Give it a coupla thinks,” he finishes up, and drifts away casual.

I looks around expecting a guy in blue with a bunch of keys to grab him, but nothing like that don’t happen. Dizzy and woozy, I drifts across the street to the restaurant Luke told me about and squats me down.

“What’ll you have?” asks the waiter.

“A cup of tea, God forbid,” says I.

It’s wonderful what a little oolong will do for a lad that gets the kind he means instead of the sort he asks for, and right away I begins to perk up some. But it don’t last long. I’m about to yell for an encore when I looks up to see a feller standing besides me, a stout, surtaxy appearing citizen with a wide grin.

“Know who I am?” he inquires.

“Considering the luck I been in all day,” I answers, “you couldn’t be nothing excepting a revenue agent.”

“My card, Mr. O’Day,” says he, and slips it.

“‘August P. Stevens,’” I reads aloud, and then to myselfs, “‘representing the Universal Outdoor Co.’”

“You cover all that territory by yourselfs?” I asks.

“No,” he comes back; “I’m mostly in Albany and Washington.”

“What do you sell,” I wants to know, “scenery or air?”

“I don’t sell,” he returns, looking me straight in the eyes. “I buy.”

“What?” I asks.

“Different things,” he answers, evasive. “I suppose you know we is one of the largest sporting-goods houses in the world. Naturally, we is interested in your bill to tax golf balls and sticks. Shall I sit down?”

“If your lumbago’ll let you,” I replies; “but you might as well know later than sooner that I’ve heard enough of that bill this afternoon to last me until three weeks after my funeral. I ain’t even sure I’m gonna flip it into the hopper.”

“The boys around here,” says Stevens, “’ll tell you that I’m a square shooter and don’t mince up no words. With me a spade’s a spade and I know how to dig. What do you need to help you make up your mind about that bill?”

“Which way?” I mumbles, fanning for time.

What a zero brain I’d been not to get jerry to that talk of Luke and Conover about sandbags and chloroform and the such!

“Our way, of course,” answers the sportsgoods man. “You forget the golf tax and we’ll not forget you.”

“I see,” says I; “you wanna bribe me not to put the bill in.”

“Oh,” returns Stevens, “you can put it in; but it’ll get sick in the committee room, be operated on and die under the ether. All you gotta do is to let the dead stay dead and get all wound up in something else. You ain’t got a thing to lose. They ain’t no chance of jamming the tax over and — ”

“What do you wanna buy me off for then?” I cuts in.

“Well,” says Stevens, “they is always a outside possibility of anything going through in the last-minute rush. Besides, we don’t wanna have taxes on balls and clubs even discussed.”

“You can’t stop that,” I retorts. “I’m full of it now.”

“Full of what?” he inquires.

“Disgust,” I snaps, and ducks outta the place.

IV

They ain’t no meeting of the legislature the next day, and I runs down to Doughmore, first having wired Cravens that I was coming and for him to meet me. I ain’t one of them holier than thous, but raw work always did get me sore, even in them times when I didn’t ask a dollar bill for references. Luke sees right off that I’m riled.

“Do I look like a grafter?” I asks.

“The light ain’t so good here,” he comes, back, calm. “What makes you doubtful?

I cuts loose and tells him everything that happened to me in Albany after he left. He listens with about as much excitement as I was retailing a bright crack pulled by my third cousin’s infant progeny.

“You don’t seem surprised none,” I remarks at the finish. “Is they all dips up in Albany?”

“No,” replies Luke, “they is about 95 percent honest; but at every session in every legislature they is always a few sandbaggers — guys that push in stick-up bills, not with any hopes of passing ’em, but on it gamble that somebody will get all scared up and buy ’em off. The railroads used to be the prize marks, but — ”

“Say,” I shoots out a yelp, “you ain’t got no ideas that I’m a sandbagger, is you?”

“Well,” returns Cravens, “at first I thought that blah of yours about golf and ducks was just some pretty fun you was having with the Doughmorons; but when it flopped with them and you kept right on yelling tax, even in front of the governor, I begun to get a little suspicious.”

“Honey sweets the Malay’s pants!” I hollers.

“Huh?” inquires Luke.

“That’s Latin,” I explains, “for lads with evil minds that thinks everybody else is got ’em.”

“Evil mind, eh?” says Cravens, kinda peevish. “Any bird that’ll go to the front for a new nuisance tax, when everybody in the country is nearly bent over double carrying the load of ’em they got now is either a stupe or a grafter. And you ain’t so stupish.’

“Damn it,” I barks, “I’ll — ”

“Listen to me,” interrupts Luke. “I ain’t calling you a crook, but what do you expect people’ll think of a bobo in these times that’ll talk up another gouge, and picks out a nice juicy game like golf for the victim?”

“I was only kidding,” I mumbles, feeble;

“I suppose,” admits the chairman; “but like the feller remarked after lugging careless baby six blocks, they is such a thing as carrying a kid too far.”

“It seems to me,” says I, suddenly remembering his stuff in Albany, “you was willing to take your bit.”

“I was,” he answers, cool, “I don’t never throw no spoons away when it’s raining soup.”

“Gosh,” I groans, “I’m in a swell fix. If I don’t introduce that bill now they’ll say I been bought off. If I does, I’ll have to go to the mat for it and keep fighting all the time I’m gonna resign,” I announces, blunt.

“That’ll be the worst yet,” says Cravens “Then they’ll figure you was bought off good and was afraid of a investigation.”

“What shall I do?” I asks.

“Just forget all about it,” advises Luke. “I’ll fix things with Stevens and Conover so nothing’ll ever be mentioned about the golf bill.”

“Sure you can?” I wants to know.

“Certain sure,” says Cravens. “Won’ I the guy that sent ’em to see you?

On the way to the house I meets up with Lizzie. “I just been to the Monday Club,” she tells me. “You still wanna hire a hall?”

“No,” I answers, “not a hall — a hole.”

“A hole?” repeats Lizzie. “What you gonna do with a hole?”

“Crawl in,” says I.

Featured image: “Flying codfish! And you’re the kinda guy that’s gonna make laws for fifteen million people!” (Illustrated by Tony Sarg)

Clap Your Hands

Gia’s mother had the English written down on an envelope. She whispered the words as they walked, because Gia couldn’t be certain she spelled them all correctly. Her mother wouldn’t pass her second-grade teacher an error-filled note. Mrs. Klein was a dottore, an expert. Their family must present well. Gia was never to show a brutta figura, her ugly side, to the world. This was very important, very Italian.

Gia could remember the smells of lemon and sea from their old apartment in Nervi, the bright colors of the old stone buildings, but she no longer felt the pull of Italian ways, just as she no longer dreamed in her first language. She kept both these truths from her parents. Gia was sure they would find them ugly, even if she did not.

When they reached her classroom, it was the vice principal, Mr. Puhl, who greeted them. “Good morning,” he said to Gia. “You are …”

“Vespucci, Gianna Maria,” her mother answered. She forgot the American order. In Italy your last name, which represented your family, was most important, but here — where every tongue tripped over the syllables — it only meant different.

“Oh, our Eye-talian,” he said. Gia was happy her father was away, cooking at his boss’s new restaurant. He gave pronunciation lessons. Italian was like singing — you had to make the right sounds or it was awful to hear. “Mrs. Klein is sick today. You’ll be in with Miss Cooper this morning.”

Her mother breathed in deep. “About Il Museo Dinosaur,” she began. The practice had worked. She pronounced dinosaur well, cutting hard at the end so the R didn’t get mushed by a vowel.

Mr. Puhl scrunched his face and turned to Gia. This happened every day, with both her parents, and it felt worse than ugly. Her mother had trouble sticking with English only, but museo was so close, and where else would you see a dinosaur, except for Barney on TV? Second graders took the same field trip every year. Gia hated adults sometimes. They made easy things so hard.

Gia checked with her mother. Mrs. Klein waited patiently through her fumbles; Mr. Puhl obviously would not. Her mother looked at the envelope again, her knuckles white, but she tapped Gia’s shoulder, her signal to take over. “My mother has questions about the field trip. She wants to know more about the museum and why we’re coming back at dinnertime.”

Mr. Puhl showed Gia his teeth but continued to look confused. “You don’t have to go.” He glanced at his watch. “You can spend the afternoon in another classroom.”

Gia translated, and her mother squeezed her shoulder. She knew Gia wanted to see the dinosaur bones and the space show, but she didn’t know Manhattan, and she wasn’t sure Gia’s father would approve of the location or the hours. He had a lot of opinions about how Gia and her mother lived, but chefs didn’t like to be bothered at work, and they worked all the time. Gia’s mother had to decide. Sometimes he came home and laughed at her worries. Sometimes he yelled. This was also ugly, but he made beautiful food, which was all anyone cared about. Gia wanted her mother — and herself — to matter more, which meant returning to Italy, which Gia no longer thought of as home, even though it was. Gia was an alien, like her parents, but she didn’t feel like one unless they were around making things feel strange. The envelope bounced in her mother’s shaky hands. Gia sighed. “I can just stay home that day.”

Her mother wiped her palms on her pants, as if her sweat was making them move. “Is maybe, yes?” she said to Mr. Puhl. “But more talk for me.”

“Maybe and yes mean different things,” Mr. Puhl said, and Gia groaned, although she meant to do it only on the inside. Her mother flashed her the quit it now gesture. Rudeness to adults was ugly. Gia knew he started it wouldn’t fly as an excuse. No matter how American Gia became, her mother expected her manners to stay Italian.

“Hello,” Miss Cooper said, squeezing next to Mr. Puhl. “Are you visiting me today?”

“The address of the museo, please?” her mother read out loud. Italian was a fast language, and her mother forgot to be slow with English, which needed more space between the words. She always sped up when nervous. When she returned home, she’d call her sister, Zia Paola, and speak without practice or help from her child.

“For the field trip next week?” Miss Cooper was the new, young teacher and looked directly at Gia’s mother as she spoke. Something Mr. Puhl hadn’t done at all, something a dottore should have known to do. Her mother’s back straightened, and she offered Miss Cooper a small smile.

“I must to say where with mio marito — husband,” her mother corrected, emphasizing the H with her lips, since it was silent in Italian. Miss Cooper’s eyes were a pretty mix of green and brown, and they stayed fixed on Gia’s mother.

“You two follow me.” Miss Cooper walked them to her classroom, where she had a subway map pinned to the wall. “The Museum of Natural History is at 81st Street and Central Park West, right where the big park is.”

Miss Cooper stepped back so Gia’s mother could take a closer look. She raised the envelope and wiggled her hand. Miss Cooper passed her a pencil, and as she took notes, Miss Cooper asked Gia, “Have you been on the subway?”

Gia nodded.

“Do you know your stop?”

“Halsey Street.”

“So you ride the L train, then.” Gia nodded. Manhattan was the other direction from her father’s cousins in Canarsie, down by the ocean that smelled more like Nervi. Miss Cooper traced Gia’s finger from the museum to where the C train met the L at 14th Street. “Only one change, and you’d be home,” she said.

Her mother’s small smile grew. “Come late?” she said. “How — no.” Her mother took a deep breath. “Why. Home. Late?”

“Traffic,” Miss Cooper said. “The ride back takes time, but we give them a snack on the bus.”

Gia’s mother pulled the permission slip from her purse and signed it. Miss Cooper placed it in the basket on her desk, then she walked to the reading nook and brought back a book, Kids’ Songs Around the World. She flipped through and gestured to Gia’s mother. “Could you help me pronounce the words to this song?”

Her mother laughed and said, “Canti Batta Le Manine.”

Gia sang the “Clap Your Hands” song for Miss Cooper. Her mother relaxed, like she did when she was home, safe in her own language. When Gia finished, she waited. Miss Cooper showed her mother bella figura, the nicest compliment, and Gia would sing or do anything she wanted.

Featured image: Shutterstock

A Man of Few Words

Along with STOP and END and DANGER, Sam’s brother taught him to recognize a few other words and phrases, such as FRIEND OF THE COURT. They were the people Sam paid child support to every month. They, in turn, sent it to his ex-wife, Ember. His brother had told him, “If you ever get a letter from them, call me right away, and I’ll come over and help you with it.” But Pete had moved eight hours away for a new job. So, when it came to reading, Sam was now on his own.

When he didn’t reply to their letter, the Friend of the Court sent more. And more. The only problem was that he couldn’t read them. But he knew they had to do with his support payments.

This was all his fault, he knew. He had been mad because Ember just couldn’t seem to get to their meeting place on time or missed their appointments altogether. So he decided the money would end, too. He had a right to see Destiny on a regular basis, and since Ember wouldn’t listen to reason, he figured the checks were all he had to bargain with.

He had been planning to withhold the support checks for only a little while — just to bring Ember to her senses — but then he’d had the accident. He’d been on the line, passing a truck panel to his neighbor, but the guy was flirting with the girl next to him and took too long to reach for it. The next thing Sam knew, another panel was coming straight at him. He slipped as he tried to reach for it, messing up his back in the process. He was out of commission for weeks, which meant he got only 80 percent of his pay. The joke, once again, was on him.

There was a college kid at the plant who was taking a break from school to save up some money to go back. Sam thought he’d ask him for help with the Friend of the Court letters. Matt seemed like a nice kid — he was majoring in special ed after all — and for that reason alone he thought he could trust him.

“Hey, Matt,” he said, the next time he saw him in the cafeteria. The kid was new and usually sat by himself reading a book. “Look, I got some papers from the court I really need help with. They have to do with my visitation with my kid.”

Maybe it was the way Sam held the envelopes out to Matt, as if he was presenting a damaged child. The boy took one look and seemed to understand. “Sure, sure, I’ll help. Do you want to look them over here?”

“No. Not here. Let’s go out to lunch tomorrow. I’ll pick up the tab. That’s the least I could do.”

“You really don’t have to do that,” Matt said.

“I don’t have to, I want to.”

So, the next day they drove out to a strip mall in his truck — all paid for, he said to the kid, to let him know he could afford lunch — to a place he figured none of the other men would be. He didn’t want anybody to see him being read to like a child.

They walked to a booth at the back of the restaurant where they could have some privacy.

The boy pretended this kind of thing happened every day. He tried to look casual, like there was no shame in this.

The waitress came over and said, “You boys ready yet?”

The boy spoke slowly, pretended to read the menu aloud to himself. “Let’s see … Fish sandwich. Catwich. Flame-broiled …”

Sam jumped in. “How’re your burgers? They any good?”

“I have one practically every day for lunch,” she said, tapping her pencil on her little green pad.

Sam closed the menu and gave it back to her. “I’ll have a burger. With lettuce, ketchup, and mustard. And fries. Your fries good?”

“The onion rings are better.”

“Sold,” he said. “And a Coke.” That was the way to handle that.

The kid looked uncomfortable. Probably worried about Sam picking up the tab. “I’ll have the same.” The way he said it, like he just swallowed a bug, made Sam laugh.

“Sure thing,” she said, looking from one to the other.

Sam waited until she was out of earshot and slipped his hand into the big manila envelope he’d brought with him. “Okay,” he said. He pulled out the letters and set them on the table like he was laying out a row of hunting knives and making the kid select one.

“O-key dokey,” the kid answered, like he was trying to make a little joke, but when the boy said that, Sam began to think he hadn’t picked the right person. The little freckles on his face, the careful way he laid out his paper napkin on his lap. In fact, come to think of it, there were times Matt didn’t seem too bright for a college boy, but he was the only person Sam had now.

“I need you to tell me what these say,” Sam said. “Basically, I don’t know which way is up with all this crap. I had them all in order nice and neat, and then they slipped off the table. I put them back the best I could. Now I got a hell of a mess on my hands.”

“Well, this shouldn’t be a problem,” Matt said in a voice a little too loud for Sam’s satisfaction. He pointed to an envelope. “See, you look at the date on the envelope and then … ”

Sam looked out the window. “I can’t see the dates. I need new glasses. That’s why I can’t read what they say.” But he knew the boy knew this was just an excuse.

“Um, well, never mind about that.” The boy looked over the envelopes and shuffled them like some kind of magician, his lips pursed. “Ah,” he lowered his voice, “they’re from the Friend of the Court.”

“I know that,” Sam said. “What I need to know is what they say inside. I have a little girl. Destiny. Her mother left me and took her, and now I pay support money to the Friend of the Court every month. Some friend.”

“So, how do you write the checks?”

His brother had given him a bunch of envelopes that were addressed to the court, and each month he went to the post office or a bank and got a money order for the amount owed. He could sign his name, the letters high and wide, like a child’s. “And I print Friend of the Court on the line where you put the payment information.”

The waitress came back with their food. Both men sat silent.

“Anything else I can bring you?” she asked, her eyes resting on the envelopes.

Matt scooted them under an elbow.

Sam smiled and said, “No, thanks. I think we’re fine.”

They waited until she left.

Matt tentatively opened the envelope at the top of the pile and began reading. “Samuel Jacobson, 1320 …”

“You don’t need to read that part. What does it say after that?” He pointed to the huge block of words on the page. “What does it say here?”

The kid nodded, looking happy to be given guidance. “Okay … ’” He scanned the letter. “Basically, it says you’re behind in your child support payments and that visitations will stop completely until you make a payment and set up a schedule to pay the rest.”

“Could you read it all?” Sam said.

So now, they settled in to how this would be done. The boy went through the letters, one by one. The news wasn’t good. By the third letter the kid seemed to be comfortable at his new job, just delivering the message.

When they were done, Sam gathered up the envelopes from the table and stuffed them back into the big envelope. “I do thank you,” he said.

“For what?” the boy said, sitting back. “This is awful. I feel bad. I hate to give you such bad news.”

“I can handle it.”

“But you can’t see your little girl until you catch up with the support payments. This is terrible. And all because you were laid up. They should know that. They obviously don’t.”

The boy grabbed his burger. “I wished you’d asked for my help sooner.”

Sam felt he could take offense to that, to the word “help.” But what did it matter? The boy was right. He was helping him. And he did need help.

“Would you like me to call them for you and explain?”

Sam shook his head. “No, that’s okay. Now that I know what those letters say, I’ll call. I have to call myself.”

Ember was one of the few people who knew he couldn’t read. They’d met in high school, and in no time she figured out what scores of teachers hadn’t been able to see or didn’t care to. She had left him a note on his locker to meet her after school at her house, and when he didn’t show up, she’d been really hurt. “How could you just blow me off like that?” she said the next day at school. She was trying not to be mad, he could see, but her eyes were welling up with tears. He didn’t want to lose her, so he told her. He was worried he’d still lose her, but instead she turned all motherly toward him, touched his face and said, “It’s okay. Don’t worry about it. Look, your secret’s safe with me.”

Ember always told him he was smart. “I know you are. Everybody knows you are. I’ll help you.”

He couldn’t do the in-class writing assignments, and for that, his teachers made excuses. He was just a little hyper. He couldn’t sit still. He was a boy, after all. They let him turn in his papers late.

So Ember would come over after school and coach him, but, with his parents and brother at work, their after-school meetings usually led to other things.

She ended up writing all his essays for him, reading assignments to him after school, and covering for him with friends. They got married the summer after graduation.

Despite his problem with reading, he thought his and Ember’s relationship had been pretty good. She took care of things that needed to be read the same way he fixed a flat tire or maintained the car and the house. But when Destiny was born, he had to leave the important things to Ember, like reading the directions on medicine bottles or the notes from daycare. But out of the blue one day, she asked him, “What if something happens to me? How would you deal with having to take care of Destiny?” He told her he’d make do, he had before he met her and he did it when she wasn’t around. “Making do isn’t good enough when you have a baby, Sam,” she had said, and he saw something change in her after that. She was less patient with him, quicker to judge.

“The problem is that you’re stubborn, Sam,” she started saying. “Just plain stubborn. You’d learn to read if you just put your mind to it.”

He knew putting his mind to it wasn’t the problem. He remembered being in first grade, with all the other kids around him who were picking up words — all of a sudden, learning how to read. Sounding the words out, then smoother and smoother like planing wood the sounds turned into words, the words into sentences. It was like, one by one, a switch within them was being turned on. But it never was turned on in him. He waited for it but it never came. The words still looked like squiggles. He had a good memory, and that saved him. He could hear something once and remember it, then repeat it when it was his turn to read. He was a good kid, and that saved him, too. His family moved around a lot when he was in elementary school. His father just didn’t seem to be able to keep a job. “Last hired, first fired,” he always said. Sam went to a lot of different schools, sometimes moving in the middle of the year. Their neighborhoods were usually rough ones, and the teachers didn’t want trouble. For that alone, he was passed from grade to grade. He was held back only once, and that was the year he had mono.

He let Ember try to teach him. That was a disaster. He couldn’t stand to see her cringe when he stumbled or missed a word, a look of utter disbelief on her face. He knew she was trying to be supportive but her face got tighter and tighter as she tried to make it look as if she wasn’t ashamed for him, her mouth finally becoming a thin line, as if she was sucking in the words she wanted to say so they wouldn’t escape.

Sam called the Friend of the Court to explain his circumstances. He was back at work now. He’d catch up on the payments. He wanted them to make out a new payment schedule. But no matter what he said, the woman who answered the phone would say only, “Put it in writing.”

When he saw Matt, he told him, “You were right. We have to write a letter.”

He and Matt met the next day, the same routine. This time, the boy brought along a pen, paper, envelopes, stamps.

They got the table at the far corner again.

“Lucky for us they don’t get much business,” Sam said.

The waitress came for their order. “You writing a book there?” she asked, pointing at the pad of paper with her pen.

“I broke my glasses,” Sam said. “My nephew here has to read my paperwork for me.”

After she left, Matt said, “So, should I call you Uncle Sam now?”

They laughed.

They waited until the waitress gave the order to the cook and tended to a new table, far from theirs. Matt said “Shoot” and picked up pen and paper.

“I know how to do this,” Sam said. “I know what she told me, the Friend of the Court.”

“What did she tell you?”

“That’s my business,” Sam said.

Matt pushed the pen and paper away. “Sam. I’m supposed to help you and you won’t fill me in on the whole story. What she said matters. It matters in how I put things down for you.”

Sam said nothing, just stared.

Matt lowered his voice. “It’s just that I can’t read your mind, you know.”

Sam fumed, got out his lighter, the one his brother gave him for Christmas years ago, when he had the motorcycle. The silhouette of a beautiful woman’s body, the curve of her spine like the letter S, so perfect, hair so long, and the HD for Harley Davidson fitted tightly behind her like a dress she’d just taken off that still held the shape of her body.

He wanted a cigarette but was trying to quit. Besides, you couldn’t smoke in restaurants anymore, which was probably a good thing. He kept opening and closing the lighter.

“That’s a beauty,” Matt said.

“Here.” Sam handed him the lighter. “Have a look.”

“Do you ride?” Matt asked, handing it back.

“I used to,” he said. “Ember made me give it up when she had the baby. One of the hardest things I’ve ever done was to sell that bike. The only person who offered me what it was worth was a guy who had hardly ever been on a bike. Can you imagine? The only thing that made me feel better was all the stuff I bought for Destiny with it. We did her room up real nice. Even started a little college fund for her. That made me feel good.”

Matt looked at him. “Maybe we should write about that in the letter. What you just said.”

“No way.”

“I just mean … it’s so hard. I’m not trying to find out your business. You know,” Matt said, leaning forward. He looked around for the waitress and said, real low, “You know, there are classes for … ”

Sam thought the kid was going to say, people like you.

“I could teach you,” Matt said. He started to get enthusiastic, rearranging the papers all over the table like it was his own little desk. “I’ve been thinking I wanted to get back into doing some volunteer work.”

“Volunteer work?” Sam couldn’t believe his ears. He wasn’t a man asking for a favor any longer. Now he was an entire charity project.

“Sure, I’d be happy to do that for you.”

It was the words “for you” that really killed Sam. For you.

Matt kept his voice low. “When I was in college, I volunteered in this literacy program, teaching people how to read. I know how to do it.”

Sam looked at him. Matt’s eyes were light brown with little flecks of green in them. He’d trusted the kid this far and he hadn’t failed him. Maybe he could trust him with this.

“Do you know your alphabet? Your letters?” Matt asked.

Sam nodded.

“Well, that’s great. That’s a great start. Some people don’t know their letters. So you’re starting from a good place.”

The next thing was hard for Sam to say. “I know the letters all right but I can’t seem to put them together into words.”

“That’s okay. That’ll come next. It takes a little time.”

They were quiet for a while. Then Matt said, “I have a theory.”

“What’s that?”

“I noticed that the people who don’t want to start with kid books don’t do as well as the other folks. Their progress is a lot slower.”

“I don’t want to read baby books. I want to read real books.”

“Sam, I’m telling you. It’s like our brains are wired a certain way. You have to start out with the basics, sort of train your brain to absorb the words.”

Sam slapped the lighter down on the table. “Look, man. I really just need to have one letter written. My daughter has a birthday coming up in a couple of months. I want to see her for her birthday. I don’t want her to think her father missed her birthday.”

His voice was not going to crack. He made a big deal of reaching inside his wallet to get the money order. Largest one he’d ever bought. He’d catch up. He knew he would.

Matt put the money order in the envelope and addressed it. He nodded. “Okay,” he said. “But if you ever need anything else …” Then he got busy with the letter explaining how much and when Sam could pay.

And now, everything reminded him of his daughter: the toys and clothes she had left behind when she visited, a commercial on TV for a baby doll he thought she might like. He didn’t like the latest doll Ember had bought her. With its Goth, cat’s-eye makeup and torn, slutty clothing, it looked more like a tiny teen hooker than a little girl’s doll. One time, he even thought he saw Destiny on the street on his way to the hardware store and his heart brightened and quickened. He didn’t recognize the woman she was with, but it could have been a babysitter or a friend of Ember’s. The little girl had the same shade of blonde hair, a similar blue coat like the one he got her last Christmas, but it wasn’t Destiny. In fact, he was shocked at how he could have even thought it was her. And he was afraid for a second that the girl’s mother might have worried about the attention he was paying her daughter, how he turned around and smiled at the girl as he passed.

Three weeks after their lunch, Sam called Matt’s name across the lunchroom. Threw the lighter in his direction. Matt almost didn’t catch it, even though Sam had given him plenty of time to see it coming and a straight, slow pitch.

Matt walked over to Sam. “It’s beautiful,” Matt said. “I can’t accept this.”

“Don’t be such a college boy,” Sam said, and Matt laughed.

They sat down together at a table farthest away from their coworkers. Matt asked, “So you’ve seen your daughter? Things are straightened out?”

“Not yet. But the Friend of the Court is letting me send a birthday card to the house. They sent me their new address.” He had bought a card on his way to work, signed it DAD in big, gawky letters, and gave the sealed envelope to Matt to be addressed.

“I can talk to Destiny on her birthday,” Sam said. “And they said that the visits can start again next month. As long as there’s no trouble between me and her mom. Looks like her mom’s accepted the payment schedule.”

“That’s great, Sam. That’s great. And look, if you ever need me again. I’m serious about my offer.”

But with this, Sam got up from the table and shoved off, still smiling, as if he hadn’t heard a thing.

Sometimes Sam felt as if his whole life was one work-around after another. When you don’t know how to read, you memorize the shape of certain letters you need. A teacher hands you a book and tells you to read it out loud, but you tell her you forgot your glasses. You forget your glasses the next day and the next and they just figure out you’re poor and won’t be bringing your glasses anytime soon. The school nurse gives you an eye test, which you flunk on purpose so they still think your eyes really are bad. They refer you to an eye doctor, but you never show up with those new glasses. So, they skip over you during reading time because they don’t want to embarrass you. You pick up a job application and tell the manager that you can’t fill it out right then because you have to take your mother to a doctor’s appointment. You ask politely if you can fill it out at home and bring it back. And they’re fine with that because everybody’s in a rush and they’re just happy to get a body to fill that job. You get your brother to fill out all your job applications, do your health forms, prepare your taxes. When you get hired, you show up on time and you get along with everybody and no one’s the wiser. Now that you’ve been at the plant ten years, there’s no need to look for a job anymore, no more applications to fill out, no letters of introduction to write. Then all of a sudden, there’s this.

On his daughter’s birthday, he sat on his bed all night and waited for her call, phone in hand. He and Ember had had so much fun setting up for Destiny’s birthday parties. She was a good mother. She’d been a good wife, until she wasn’t. Some things break in ways you can’t see and because you can’t see them, there’s no way you can fix it. Sometimes when he looked back at it all, it seemed as if one day Ember was kind and supportive and understanding and the next she was impatient and mean and distant. It was like that light that went on in other kids’ heads when they learned to read. She saw the light, and he still didn’t. And, just like reading, he didn’t even know where the switch was.

Five minutes before Destiny’s bedtime, his phone rang.

“Hi, Daddy!” she fairly screamed.

“Hi, punkin! Oh, it’s so good to talk to you. I miss you.”

“I miss you, too, Daddy. That was a funny card you sent.”

“Was it a funny card, punkin? Did you like it?”

“Why did you send me a boy’s card?”

He felt his smile dissolve and the heat of embarrassment creep through his body like a bad flu. He thought of the drawing of the child on that card. Surely, it was a little girl, with short blond hair, like Destiny’s. That was why he bought it. Because the child looked like her. He thought she’d like that.

He couldn’t read it, of course, but he could make out the H and the B, which he knew were for Happy Birthday. And there were candles and a cake on the front of the card so he knew it was a birthday card. And a big number 6 for her age.

“Snips and snails and puppy dog tails,” his little girl was saying. “That’s what little boys are made of. That’s what the card says, Daddy.” He could picture her pursing her lips together like she did when she was mad.

“Why would you do that, Daddy?”

He felt his whole face contract as if in pain. What could he say?

“Oh, you’re so smart,” he told her. “You’re Daddy’s smart little girl. I played a trick, and you figured it out.”

“Well, of course I did, Daddy! It’s right there on the card. I read it.”

When Destiny was really little and gave him a book to read, he would make up stories to go along with the pictures since she didn’t know how to read yet. He had been so relieved when she started reading in kindergarten. She wasn’t afflicted with whatever it was that stopped his brain from putting simple letters together to make words. He hadn’t passed that on to her, and he thanked God for that. He thought of something he could say to her, another excuse.

“Actually, honey, when I went to the drugstore to buy the card, I forgot my glasses, so I couldn’t see the writing very well. I thought the little girl looked like you.”

“But it’s not a girl, it’s a boy. Why did you do that, Daddy?” repeating herself like she always did when she was tired.

He heard Ember say, “Tell your Daddy goodbye now. You have to go to bed.”

“Goodbye, Daddy. See you soon I hope. I love you.”

He started to say, “I love you, too,” and wanted her to know that the money he put inside the card was for her to buy herself a toy she wanted, but Ember had the phone now. She whispered, “I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again. You’re a smart guy. You can do this. Get some help before she figures it out.”