Titanic Fanatics

On an overcast June day in 2015, Dave Gardner, a short man with graying hair under his beanie, was intently focused on photographing the corroded archway of a long-disused Hudson River pier in lower Manhattan. As disinterested passersby ignored him, he took picture after picture, all the while simultaneously assessing possible ways to get onto the rotting pier.

A little more than a century before, an excited crowd of 30,000 people were massed right where Gardner stood now and stretching back several city blocks. They were anxiously awaiting the 705 survivors of the Titanic arriving on the ship that rescued them, RMS Carpathia.

Gardner’s a tour guide who considers it his responsibility to document Titanic landmarks in New York. Now he was paying what might be his final respects before the pier was scheduled to be demolished, to be replaced by a floating park. He was there to take what might be the last photos of the pier, but he wanted to do more.

He walked an 8-foot-tall fence, looking for a place to slip through. If he could find that, he could do it: He could save some rusted pipe, hunks of asphalt, and a few old bricks.

Suddenly he saw the word ROSE — the name of Kate Winslet’s character in the 1997 film Titanic — stamped on the side of a heap of bricks from the pier. “When I saw that,” Gardner later wrote on Facebook, “I wanted them … bad.”

In truth, it was really the manufacturer’s name. And, granted, Rose was fictional — but Gardner knew fellow enthusiasts would be thrilled to see and own these bricks, even though the original pier actually had burned down in 1932 and collapsed into the Hudson.

Gardner returned at night, slipped in, and searched through the demolition site. As he went, he shoved bricks and fragments of metal and concrete into a tote bag. He was after only the best rubble. Then he reemerged, undetected, happy to have saved something from the location where survivors might have taken their first steps on land after history’s most famous maritime disaster.

Gardner is just one of a global community of Titanic enthusiasts that runs the gamut from Leonardo DiCaprio fans to professional wreck divers. They all share a fascination with the immortal disaster, bonding over the human tragedy as well as the trappings of the Gilded Age. And today, this community is reinventing itself for social media, its leaders seeking to find ways to keep the artifacts intact and the story relevant. It’s the latest stage in the idiosyncratic history of an intercontinental subculture full of historians, amateur sleuths, self-made lecturers, and memorabilia collectors.

But why love the Titanic? Why this fervor for something so grim and remote? What makes people spend leisurely afternoons reading everything they can about the many who died of drowning or hypothermia? Or pay a fortune for waterlogged coal from a boat that wouldn’t float and canned saltwater that might have touched it? Or trespass to steal bricks from a pier even the city doesn’t want?

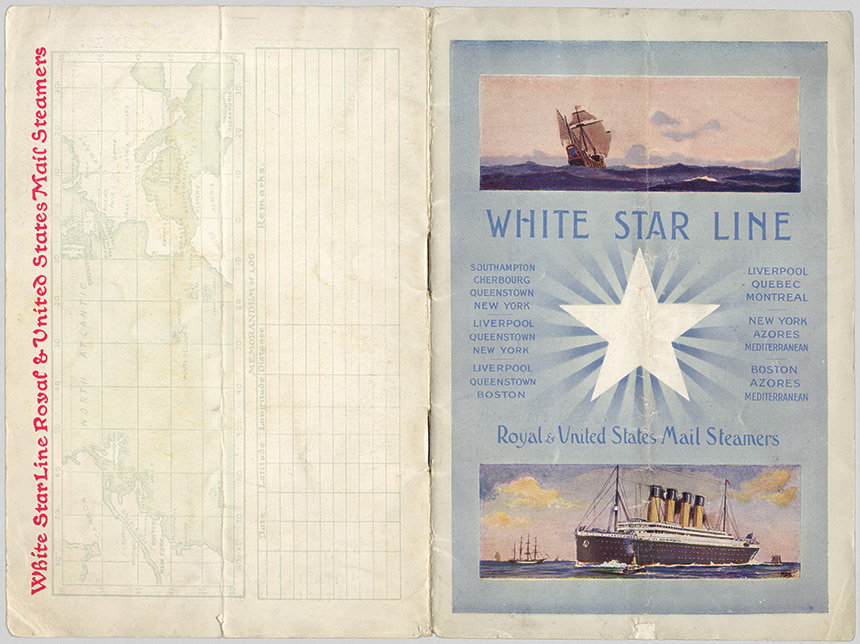

The Titanic had been the subject of international fascination even before the sinking: The shipping company White Star Line’s response to their competitor Cunard’s swift ocean liners was building ships unprecedented in size and luxury. Titanic’s grandeur and intricate system of water-tight bulkheads gained it a reputation as an unsinkable palace. So, when it struck an iceberg and sank in the North Atlantic Ocean on April 15, 1912, the public response was grand-scale shock and mourning for the 1,500 people lost on the maiden voyage.

Another reason Titanic’s story is so much more compelling than other maritime tragedies has to do with time. Consider, for example, the sinking by the Germans of RMS Lusitania, an English ocean liner, in 1915, with the loss of 1,193 people. “The problem with the Lusitania in terms of being on anybody’s radar is that the ship sank in 18 minutes. There wasn’t enough time for stories to play out and for interpersonal dramas to take place,” says historian and president of the Titanic International Society Charles Haas. “Titanic, you have two hours–plus where we see human behavior at its best and its worst.”

A Texas collector spent approximately £78,000 to own a key to the ship’s chartroom.

And since there were so many survivors of Titanic to recall in detail the incredible human dramas of those horrible final hours, the world has been captivated by them ever since as the tragedy remained etched in the public consciousness, in movies and books, throughout two world wars.

But the tale of the Titanic fans and enthusiasts begins more than 40 years after the tragedy. That’s when 14-year-old Edward Kamuda first saw the 1953 film Titanic in his family’s small theater in Indian Orchard, Massachusetts. “If the Titanic (the memory, that is, not the ship) never disappeared, its presence after 1913 was occasional or marginal until it was rediscovered for new audiences in the 1950s as a commercial phenomenon,” Steve Biel, a Harvard history professor, wrote in his 1996 cultural history of the ship, Down with the Old Canoe.

As Kamuda watched Titanic sinking in the film, with the doomed passengers singing “Nearer My God to Thee,” some emotional needle was threaded within him. According to the Titanic Historical Society, he began trying to find others fascinated by Titanic, contacting any aficionados he could through ads, articles, and mutual pen pals. Five years later, when the film A Night to Remember — based on Walter Lord’s book about the sinking — was in theaters, Kamuda used a survivor list sent with publicity packages to contact them about their experiences.

Kamuda’s efforts to create a group of enthusiasts took on greater urgency in 1963, when he learned Walter Belford — featured in Lord’s book — had died and his belongings were posthumously discarded. Kamuda was sure historic relics were lost. He wouldn’t let it happen again. (Ironically, Belford’s claim to be a Titanic survivor was a hoax.)

So on July 7, 1963, seven people embarked on a new kind of project at Ed Kamuda’s Massachusetts home: a kind of history hobbyists Ocean’s 11, composed of survivors and Kamuda’s network. The group’s newsletter carried the details: There was Kamuda himself and his sister Barbara, who provided Titanic books and films, a location, and the plan. There was Frank Casilio, with his meticulous Titanic scrapbooks. Joseph Carvalho and his wife arrived with a model of the ship he’d spent a year building. Teenager Michael Ravetti brought a collection of Titanic-related news and magazine clippings. Finally, Bob Gibbons, who couldn’t show up in person, called in from Missouri.

By early evening, the men were founding members of the world’s first group for Titanic fanatics — Titanic Enthusiasts of America (renamed the Titanic Historical Society after a survivor questioned saying they were “enthusiastic” about a tragedy). They began seeking members. Over several decades, their efforts — bolstered by the 1985 discovery of the wreck and James Cameron’s enormously successful 1997 film — resulted in a sprawling membership.

Since that time, numerous Titanic appreciation societies have been seeded across the Earth. Many work to preserve knowledge about the sinking and the few physical mementos they can. This becomes more important with time, as the wreck is degraded by its environment and controversial salvage projects struggle to find court approval. Additionally, as of the 100th anniversary of the sinking in 2012, the wreck was protected by UNESCO, increasing pressure to preserve it as it is.

Aficionados share stories and items through themed meetings, but mostly associate through Facebook groups. Kamuda’s Titanic Historical Society claims more than 2,300 members on Facebook. But enthusiasts don’t settle for shared digital space. What is most desired is a closer connection to those who went down with the ship and to the ship itself.

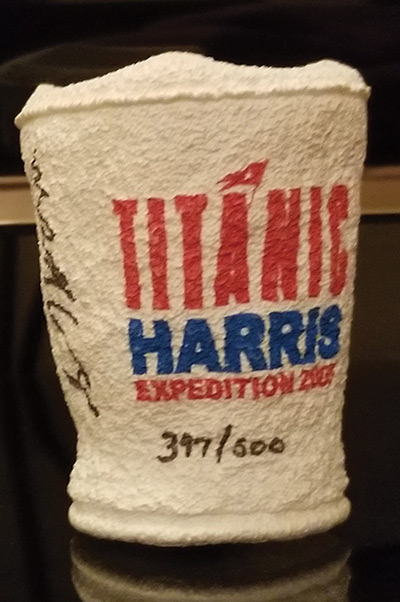

According to the BBC, a Texas collector spent approximately £78,000 to own a key to the ship’s chartroom; a 2016 New York Times article notes that a Halifax graveyard holding 121 bodies recovered from Titanic receives approximately 160,000 visitors annually and closed access to tour buses because so many rolled onto its grounds; and the CBC reported that Canada’s largest private collection contains 1,000 Titanic items. This includes, according to owner Rene Bergeron, a dozen Styrofoam cups brought to the wreck by divers to demonstrate water pressure, suitably crushed by it, and now worth up to $150 each — even though they weren’t even originally on the ship!

Sifting through a collection of more than 120 Titanic-related items in her family’s New Jersey home — chunks of rusted metal, shards of coal, and a crushed Styrofoam cup — Christie Seyglinski gently touched pamphlets and reprinted Senate records. “I have a combination of both floating debris and debris that was actually at the bottom of the ocean,” she said with proprietary pride.

In her 20s, she’s among the younger enthusiasts. Like Kamuda, she was hooked by a movie: At 4 she saw James Cameron’s Titanic, and it’s been a love affair with the ship ever since.

She’s privileged because she met the last living survivor, Millvina Dean — only a newborn during the sinking — before Dean died in 2009. Seyglinski keeps framed letters from Dean and a sketch of the ship’s grand staircase which Dean signed. Several enthusiasts have a specific name on the passenger and crew list for whom they feel special fondness. But only a few actually knew passengers.

When the 100th anniversary came, Seyglinski took a cruise to the wreck site at 41°43’57” N, 49°56’49” W — coordinates dear to her heart. The waters were still and the weather mild as the cruise ship floated more than two miles above the Titanic’s sunken bow. She threw flowers and a letter for those on board the Titanic into the sea.

Six years later, she laughed bashfully and wiped away a tear as she reflected on the memorial service over the wreck from the warmth of her personal collection of memorabilia. “It was probably the most amazing thing I’ve ever done, just being there 100 years to the second,” she said.

Seyglinski keeps a first-edition copy of Filson Young’s book Titanic, published about a month after the disaster, which a friend gave her on the anniversary cruise. Her friend glued a treasured relic from The Big Piece — the section of hull raised from the wreck in 1998 — into its front cover: a patch of horsehair porthole insulation.

Günter Bäbler, cofounder of the Swiss Titanic Society, was present when The Big Piece was salvaged. Biel’s book says he’d been brought along as “the world’s foremost expert on Swiss Titanic passengers.”

Bäbler’s an unusually reserved aficionado — fascinated more by what Titanic tells him about other ships and passengers of the time than the ship itself. An analytical, pragmatic man with prominent eyebrows and a soft smile, he prides himself on neutral and objective scholarship. All the same, he felt an aura of history as he stood on deck, hovering over the Titanic’s remains.

“I had this feeling of being late,” he said. “You’re physically close to something that isn’t there.”

Bäbler was 10 years old when he first heard about Titanic in class. Bäbler remembered asking his teacher why those on board didn’t climb the iceberg. The teacher couldn’t answer. This left Bäbler with a simmering curiosity.

The more serious enthusiasts pride themselves on studying real people, and consider those who simply want to swoon over Leo DiCaprio shivering on a sound stage as, well, gauche.

His local library had only two books on the sinking, but he was pulled along by a desire to fill in the gaps and resolve the contradictions he found. He, like many enthusiasts, considers part of the appeal of the subject the staggering amount to discover. He’s plotted the GPS locations of more than 3,000 Titanic-related sites at TitanicMap.org and sprinkled in coordinates of other sinkings he believes deserve attention. And he’s written a book, Guide to the Crew of the Titanic: The Structure of Working Aboard the Legendary Liner.

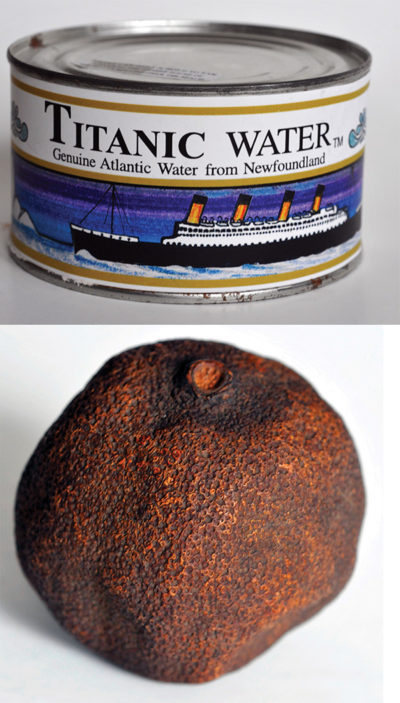

Bäbler specializes in collecting papers, relishing details that authenticate them: the stamp of a press ever-so-slightly raised on a passenger list’s back, the distinctive gloss of discontinued photograph papers, the particular color of a company’s authentic ink. But his collection ranges far wider: a 1990s portable steamer for stripping wallpaper, apparently collected simply because of its name, Titanic 2000; salt water — canned in Newfoundland in 1998 — that “may have touched the great ship” (exactly how unique a distinction this is 86 years after the sinking is something the tin does not disclose); even a desiccated orange purportedly brought home in a survivor’s coat pocket and long preserved before finding its way to Bäbler. “I have to laugh about myself a bit, that I have an orange from Titanic,” he said, “and I keep it in a bank safe.”

Like Bäbler, some enthusiasts become authors while others, like self-made Titanic lecturer and professional gardener Will Kindler, give back through artifact curation. “It’s so important that these items be preserved as much as possible, and especially in groups that can be viewed and shared,” he explained in an email. “This history belongs to all of us.”

Kindler, who’s in his 30s, spends most of his free time studying the ship or using 250 search terms to sweep online auctions for items to contribute to public exhibits, especially in spring, when the anniversary of the sinking rolls around. “The fever kicks in every year,” he said, starting in March and burning him out by April 14. Afterward he cools down by focusing on less in-demand maritime disasters. Inevitably, though, he returns to Titanic.

As with so many other things, the Information Age changed the Titanic fan community. In the past, finding another enthusiast involved attending a convention, seeking out addresses of people featured in Kamuda’s journal The Commutator — or meeting by coincidence, as when historians Charles Haas and Jack Eaton, cofounders of the Titanic International Society, collided in the New York Public Library’s card indexes in the 1970s and began a decades-long friendship.

Haas is a burly man in his 70s, with a sonorous voice, immaculate diction, and an upper lip that dips in the center, giving him a falconish look. Though a respected Titanic expert, he stayed a high school teacher until retirement because of the difficulties of transmuting the work into a career. (Bäbler puts a loose guess at only four or five individuals deriving a living from in-depth, original Titanic research.)

In the ’80s, Haas created the Titanic International Society, a pro-salvage group. He prides himself on their officer elections and member surveys meant to stoke fraternity among enthusiasts. “They used to be called affinity groups,” Haas said of cohorts such as Titanic societies, “and you’d develop an affinity not only for the subject matter but for one another.”

Haas worried that groups based mainly online dilute the possibility of forming personal relationships. In contrast, Bäbler — once reliant on the mail to contact enthusiasts — is pleased newcomers today find it easy to locate themselves in a wider group. Many prefer connecting to the community through Facebook because it’s more relaxed and egalitarian.

The downside of Facebook is being overwhelmed by hordes of single-minded James Cameron movie buffs, those who wish for nothing more than to memorialize film characters who were never alive to begin with. The more serious enthusiasts pride themselves on studying real people, and consider those who simply want to swoon over Leo DiCaprio shivering on a sound stage as, well, gauche.

Though united in their interest in a singular event, Titanic historians, fans, and collectors certainly disagree on how to go about their pursuit in good taste and what the boundaries should be. Tour guide Dave Gardner, for example, forgives Titanic-themed inflatable slides, but thinks an internet meme about Titanic victims livestreaming as they drown is mean-spirited. Kindler thinks Titanic-themed inflatable slides are ludicrous, and an Australian billionaire’s long-deferred proposal to reconstruct Titanic is exploitative — though he confesses he’d visit the attraction if it docked locally. Others, such as Bäbler, simply hope tchotchkes such as Titanic-themed bathplugs or ice cube molds are a gateway to more serious interest in the subject.

Every year, as the sinking’s anniversary approaches, enthusiasts prepare for the big day: Haas gathers research for radio and newspaper interviews; Seyglinski stays alert for Titanic gatherings; last year Bäbler reconstructed a passenger list for Carpathia (which was itself sunk in July 1918 after being torpedoed by a German U-boat) while continuing to photograph graves and memorials for TitanicMap.org.

And every April, Dave Gardner guides his earnest and curious tour groups. He takes them to the High Line, an elevated track originally built to unload ships, which is now preserved as a park. Casting his hand out over the city, away from the Hudson, he’ll tell them that the crowd that welcomed survivors on the Carpathia stretched several city blocks back from the river. And then, turning to the piers, he’ll point to where Titanic was to dock (now transformed into a golf driving range).

His tours hit their zenith on the disaster’s anniversary, April 15: “That’s Christmas,” he says, “and I’m Santa Claus.”

Emlyn Cameron is a politics- and history-focused journalist in Brooklyn, New York. Growing up, he was fascinated by the Titanic and celebrated the centenary at his family’s home in California. He graduated from Columbia University’s journalism school in 2019.

This is an excerpt of an article from the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Library of Congress