50 Years Ago, Flip Wilson Changed the Face of TV Comedy

Flip Wilson started working his way up the comedy ranks in the 1950s, but his big break came in 1965. That’s when Red Foxx told Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show that Wilson was the funniest comedian out there. Carson put him on, and stardom followed. Within five short years, Wilson was at the helm of his own variety and sketch-comedy show, The Flip Wilson Show. The trailblazing series saw Wilson become one of the most visible and popular Black entertainers in America. On the 50th anniversary of its first episode, here’s a look back at Wilson’s journey and how his show became a platform that propelled other artists forward.

Clerow Wilson Jr. was born in 1933. His mother left his father, him, and his nine siblings when he was seven; as a result, Wilson and a number of his siblings went to foster homes. Wilson joined the Air Force when he was 16 (yes, he lied about his age). Wilson’s natural instincts for entertaining emerged, and his gift for comedy soon saw him sent from base to base to improve morale. Some of his fellow servicemen would describe him as “flipped out” and called him Flip. Wilson would adopt that name and perform under it for the rest of his career.

Flip Wilson on The Ed Sullivan Show from 1970 (Uploaded to YouTube by The Ed Sullivan Show)

After the Air Force and into the early 1960s, Wilson built his comedy brand. He recorded a pair of albums, Flippin’ (1961) and Flip Wilson’s Pot Luck (1964) during this period as he performed in clubs. He also appeared regularly at the Apollo Theater. When Redd Foxx endorsed him to Johnny Carson, it facilitated his entrance onto television. In addition to multiple appearances on The Tonight Show, Wilson would appear on The Ed Sullivan Show, The Dean Martin Show, Here’s Lucy, and more. With the launch of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In in 1968, Wilson was billed as a “Regular Guest Performer” through the first four seasons.

Wilson’s growing popularity earned him a shot with his own show. The Flip Wilson Show debuted on September 17, 1970, on NBC. The program incorporated sketches along with music and celebrity guests. Wilson played a variety of recurring characters. Easily the most famous was Geraldine Jones, his take on a modern Black woman from the South. Geraldine turned out to be something of a catchphrase machine, with lines like “The Devil made me do it,” “What you see is what you get,” and “When you’re hot, you’re hot; when you’re not, you’re not” entering the cultural vocabulary.

Flip Wilson on The Midnight Special (Uploaded to YouTube by Midnight Special)

Wilson used the show as a platform for a number of other Black performers. The show included early appearances by the Jackson 5 and welcomed stalwarts like Aretha Franklin, The Temptations, The Supremes, Stevie Wonder, Ray Charles, and more. He also brought on a wide range of other guests, featuring everyone from Johnny Cash to Bing Crosby to Joan Rivers. Musical guests also frequently took part in the comedy bits. Among Wilson’s writers was legendary comic George Carlin, who himself was in the midst of a turn toward more countercultural comedy; Carlin occasionally appeared on the show as well.

In a short period of time, The Flip Wilson Show was one of the most watched programs in America, falling behind only All in the Family in 1971. It was a groundbreaking success, as Wilson became one of the few Black entertainers to be that popular with white audiences as well. The show was also recognized for its overall quality; it won two of eleven Emmy nominations and earned a Golden Globe for Wilson for Best Actor in a Television Series. Wilson’s fame grew, but the network began to resist his demands for a larger salary. As the show went on, ratings dipped (as they did for most prime-time variety shows of the period), and the series was cancelled in 1974.

Eddie Murphy and Jerry Seinfeld discuss the greatness of Flip Wilson and other comics (Uploaded to YouTube by Netflix Is A Joke)

Wilson worked regularly in comedy, television, and film over the following years. In 1983, he memorably hosted Saturday Night Live; he even played Geraldine in a sketch that “revealed” her to be the mother of Eddie Murphy’s hairdresser character, Dion. Wilson headlined the TV show People Are Funny in 1984 and was the lead in Charlie and Co. from 1985 to 1986. His last television appearance was on a 1996 episode of The Drew Carey Show. Wilson passed away from liver cancer in 1998 at the age of 64.

Wilson reached all audiences with his humor and put acts in front of audiences that might not have seen them otherwise. His influence extended into the way Americans talk; even the editing software WYSIWYG is an acronym taken from one of Geraldine’s catchphrases. He earned the admiration of comedians like Redd Foxx and Richard Pryor, worked to get the best facilities for his show, and wasn’t afraid to demand compensation commensurate with running and starring in the #2 show on television. If what we saw was what we got, then we got greatness.

Featured image: Flip Wilson as Geraldine Jones interviews Dr. David Reuben on an episode of The Flip Wilson Show (Wikimedia Commons)

Wit’s End: Everything I Needed to Know, I Learned from Cheers

This month, my children will start the school year at home. Instead of full days of 8th and 6th grade, they will have Zoom class for three hours in the morning.

If they were in the lower grades, I would be worried. But they’re strong readers, so the key battle has already been won. My favorite book in 7th grade was a 1,200-page family saga set in Wales and based on the Plantagenet family of Edward III. The Wheel of Fortune by Susan Howatch left an indelible mark on me as I absorbed its many lessons. What they taught in 7th grade history — a class called, for maximum drabness, “social studies” — I forget.

When not poring over the extramarital affairs of the Plantagenets, I watched TV, and that was where the real learning happened. The sitcom Cheers ran on NBC from 1982 to 1993, and my siblings and I watched every episode with rapt attention. The show’s creators, brothers Glen and Les Charles, seemed to me figures of immense national importance, our era’s Orville and Wilbur Wright.

Cheers was set in a Boston bar, owned by a guy whose drinking problem had destroyed his career as a professional baseball player. At age ten, this setup gave me a lot to chew on. But there was more: He carried on a flirtation with a blonde waitress, a former grad student whose book smarts were of little help in a pub setting. The shrewdest person on the show was the bar’s other waitress: a perennially angry single mom who started with four kids and proceeded to have four more with her ex-husband.

This was unlike anything in our real lives. We lived 2,000 miles from Boston in a small town surrounded by peanut fields. None of us had ever set foot inside a bar. The local watering hole was called Goober McCool’s — a place where, when I grew up, no one knew my name because it was not my scene.

So watching Cheers made us kids feel cosmopolitan and savvy. In short order, we learned that the Red Sox were a Boston baseball team and that, under the influence of alcohol, adults made foolish choices they came to regret. Meanwhile, our teachers were quizzing us on Eli Whitney. Pfft, who cared? Why study the cotton gin when you could watch Carla Tortelli slinging gin while saying:

“It was a magical moment. You know, it was like I was transported back in time. I wasn’t a tired old woman with six kids. I was a fresh young teenager with two kids.”

In fact, the wisest people on Cheers were often the ones who’d spent little time in school. A white-haired simpleton served as a sort of Zen master while polishing glasses behind the bar. (“Coach, I’m having blackouts!” “Kind of a nice break in the day, isn’t it, Sam?”)

Characters who lectured others from a position of superior knowledge were usually wrong. The clearest example was a mailman named Cliff who said things like: “It’s a little-known fact that cows were domesticated in Mesopotamia and were also used in China as guard animals for the Forbidden City.”

In fact, the Charles brothers, both of whom graduated from a small college near Los Angeles, seemed a bit jaded about people who spent half their lives in school. Their college-educated characters — writer Diane, psychiatrists Frazier and Lilith, and businesswoman Rebecca — had countless humbling interactions with the wait staff.

But the bar’s professional types were not above dishing it out, either. Lilith once described Carla as “a woman whose hair has never seen a greasy pot it couldn’t scrub clean.”

And, when introduced to Carla’s hockey player ex-husband, Frazier quipped: “Have we met? You wouldn’t, by any chance, be the bogus missing link exhibited at the Amsterdam World’s Fair?”

In the midst of this ongoing class warfare were simple drunks like Norm. One of the more wholesome role models on the show, he was an accountant who had no interests in life but drinking beer.

“Whatcha up to, Norm?” someone would say.

“My ideal weight if I were eleven feet tall.”

“What’s the story, Norm? “

“Boy meets beer. Boy drinks beer. Boy meets another beer.”

Norm advanced another of the show’s main themes: the battle of the sexes. He was always hiding out from his dreaded wife, Vera. Like Norm’s marriage, most Cheers romances were ambivalent, volatile, and steeped in mutual distrust. Here’s Sam describing his on-again, off-again relationship with Diane:

“You gotta get past this early infatuation and get to the point where you’re sick and tired of each other; then you’re ready for marriage. Look at Diane and me, we waited five years to get married. If it were up to me, we’d wait another five.”

“I thought you were seeing someone,” Diane once said to Carla, who unerringly took up with the wrong men.

“His fingerprints grew back. He had to leave the country.”

Still, the Cheers crowd clearly enjoyed, even sought out, each other’s company. Despite the characters’ differences, the bar’s overall mood was tolerant and gracious, as if the barflies sensed their troubles were all the same.

I didn’t learn algebra from Cheers, but over the years I acquired a working knowledge of how to be American. The ideal citizen was basically good-natured, willing to live and let live because one person’s foible was another one’s punchline and so contributed to the general hilarity. And everyone could drink to that.

Now, stuck at home, my daughter watches a lot of Parks and Recreation, a sitcom that ran from 2009 to 2017. Here’s the show’s most loveable character, Andy, who shines shoes for a living:

“I once forgot to brush my teeth for 5 weeks. I didn’t actually sell my car, I just forgot where I parked it. I don’t know who Al Gore is and at this point I’m too afraid to ask. When they say 2 percent milk I don’t know what the other 98 percent is. When I was a baby, my head was so big scientists did experiments on me. I once threw beer at a swan and then it attacked my niece, Rebecca.”

I’d say the ’20-’21 school year is very much in session.

Featured image: haymickey (pixabay)

The Blues Brothers Took SNL to the Big Screen

When the Not Ready for Prime Time Players hit TV in 1975, few people expected that cast members from Saturday Night Live would soon break into movies. Chevy Chase did it with his 1978 hit Foul Play; that same year, John Belushi had his own hit with National Lampoon’s Animal House. Bill Murray scored the following year with Meatballs. But the first time that SNL characters jumped to movie theaters came in 1980, when Belushi and Dan Aykroyd hit the road as Joliet Jake and Elwood Blues, The Blues Brothers.

Aykroyd and Belushi brought their Blue Brothers characters to life for the first time on the April 22, 1978 show. The original concept was simple in that they were basically just playing the part of a classic rhythm and blues show band. Aykroyd had been a blues fan and got Belushi into it during the after-parties the SNL cast would have at the Holland Tunnel Blues Bar. The pair began to sit in with local bands, and SNL band leader Howard Shore jokingly dubbed the duo the “Blues Brothers.” From there, Aykroyd and Ron Gwynne conceived an elaborate backstory for Jake and Elwood that included being raised in a Catholic orphanage and learning about music from the caretaker, Curtis.

The Blues Brothers perform “Soul Man” on SNL (Uploaded to YouTube by Saturday Night Live)

Before debuting the characters on the show, they collaborated with Paul Shaffer to assemble a legitimate band. “Blue” Lou Marini (sax) and Tom Malone (sax/trombone) had been in Blood, Sweat & Tears and were in the SNL house band. Steve Cropper (guitar) and Donald “Duck” Dunn (bass) were authoritative figures in music, having played on many Stax Records songs and been members of Booker T. & The M.G.’s. The group was rounded out by experienced players Matt “Guitar” Murphy (er, guitar) and Alan Rubin (trumpet). Willie “Too Big” Hall, who had played with Isaac Hayes on “The Theme from Shaft” and more, came in on drums. The band recorded the album Briefcase Full of Blues in 1978 while opening for Steve Martin on tour; positive reviews and their appearances on SNL drove the album to #1 on the charts. Their cover of the Sam & Dave classic “Soul Man,” which they performed on the show, went to #14.

Belushi’s star was going supernova that year. He was easily the most popular SNL player, Animal House was a huge hit, and he and Aykroyd had a #1 album. When the pair suggested that they could see the Blues Brothers on film, a studio bidding war ensued. Universal got the rights and Animal House director John Landis boarded the picture. Landis took Aykroyd’s massive story ideas (a document that took six months to create and was said to be nearly 400 pages) and turned it into a screenplay.

The “I hate Illinois Nazis” scene from The Blues Brothers. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

The story involves Elwood retrieving Jake after he gets out of prison. When the brothers discover their former orphanage may close, Jake gets a vision at a church service and decides that they need to go on “a mission from God” to reassemble the band to make enough money to save the home. Along the way, they incur the wrath of the police, a country band, Illinois Nazis, and a murderous mystery woman (Carrie Fisher). The film is filled with musical sequences featuring the likes of James Brown, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, and Cab Calloway. The production went over budget thanks to all the cameos, delays from Belushi’s legendary partying, and the record-breaking destruction of over 100 police cars. Though the studio was skeptical about the chances for success, it opened second at the box office in its first week (behind a little picture named The Empire Strikes Back) and went on to be the 10th largest hit of the entire year. The film soundtrack sold a million copies in America.

Aretha Franklin makes acting debut with ‘Blues Brothers’ role (ABC News)

Over the years, the film has become a cult classic and a regular presence in midnight screenings. It did result in a sequel years later, Blue Brothers 2000, which was both a commercial and critical flop. However, the original film proved that SNL characters could make the leap to film. In the decades since, there have been 11 films featuring characters that began as SNL sketches. Aside from The Blues Brothers, the most successful were Wayne’s World, Wayne’s World 2, A Night at the Roxbury, and Superstar (featuring Molly Shannon’s Mary Katherine Gallagher). What Saturday Night Live has proven much more than the ability to launch a film is that it’s almost unequalled as an incubator for comedic talent, with dozens and dozens of successful writers and actors heading out to put out countless acclaimed films, TV shows, and books.

The Blues Brothers remains in popular consciousness for a few reasons. The film is funny, the music is great, and there’s a deceptively heartfelt message under the car crashes; Jake and Elwood know that the orphanage gave them a chance, and they know they need to save it to help other kids that need it, too. It remains a terrific showcase for the varied talents of Belushi, who passed too soon after the film in 1982. The Brothers may have been on a mission from God, but as entertainment, the movie is still divine.

Featured image: steve white photos / Shutterstock.com

Laurel and Hardy’s Comedy Still Holds Up

In order to join the private Laurel and Hardy Appreciation Society Facebook group, one is required to submit, in writing, their favorite Laurel and Hardy scene, probably to weed out spammers and trolls. But if you want to gain membership to the Sons of the Desert — the most widespread and official club for “connoisseurs” of the comic duo — you’ll need to contact the corresponding secretary and find your local chapter, or “tent.”

For 55 years, the Sons of the Desert have made it their mission to keep Laurel and Hardy’s legacy alive across the globe. There are more than 100 “tents,” most of which are named after Laurel and Hardy’s films. The Way Out West tent is located in Los Angeles, the Boston Brats tent is, of course, in Boston, and the Unaccustomed As We Are tent is the chapter in Jakarta, Indonesia. A tent called Berth Marks meets at the Laurel and Hardy Museum in Ulverston, England, where Stan Laurel was born 130 years ago today.

Watching Laurel and Hardy’s movies now, particularly Sons of the Desert, is an exercise in discovery for the uninitiated. Their films display the timelessness of good comedy — wit, slapstick, timing — and the universality of maddening frustration over endless incompetence. Sons begins with the pair causing awkward chaos by interrupting a Shriners-type meeting to squeeze their way to two front seats, and it ends with Stan Laurel’s famous line, once they’ve both been caught lying to their wives about attending a national convention in Chicago: “Honesty is the best politics.” Laurel and Hardy were flanked by plenty of other famous, and acclaimed, comedic actors in their time — Mae West, Charlie Chaplin, the Marx Brothers — but they’ve inspired a uniquely resilient organized fanbase.

When Ron Cooper wrote about the Sons of the Desert in this magazine in 1971, he was impressed to see a sort of Laurel and Hardy revival underway. Since then, the group only appears to have grown, adding dozens of tents around the world and expanding the fanbase for the comic duo of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Cooper noted Stan Laurel’s approval of the “buff club’s” formation, and his contribution to the Greek motto on the group’s insignia: “Two Minds Without a Single Thought.”

In a 1987 documentary about the Sons of the Desert, its founder John McCabe described the group as “a set of odd, charming, curious, misplaced cherubs.” The farcical organization is run in a similarly absurd fashion as the movie it is named after. The chair is named the “Exhausted Ruler,” a malapropism uttered by Laurel when he means to say “exalted ruler,” and the group joins crossed arms to sing their chant: “We are the sons of the desert/ Having the time of our lives … ” At their biennial conventions, members (which include men and women) share memorabilia, play trivia, drink cocktails at every step (as directed by their constitution), and, of course, watch Laurel and Hardy films.

Gary Russeth, of Harlem, Georgia (Hardy’s birthplace) is the “Grand Sheik” of his local tent, and he runs a local museum. He says he grew up watching Laurel and Hardy on a nine-inch 1947 General Electric portable television set. Speaking to the pair’s enduring popularity, he says, “We have lawyers, teachers, blue- and white-collar people in the Sons of the Desert. It’s a variety of many different groups. I would see these little kids come in, and they’re so smart and they love Laurel and Hardy. It’s basic, like a cartoon. It’s just two funny guys that just constantly have one problem after another. And it’s embellished.”

The Sons‘ 2020 convention was scheduled to occur this month in Providence, Rhode Island, but it was delayed until next year. Laurel and Hardy savants need not dismay over the lack of a formal meeting, though; later this month, Laurel & Hardy: The Definitive Restorations will be released on Blu-ray.

Featured image: Laurel and Hardy in The Flying Deuces (Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

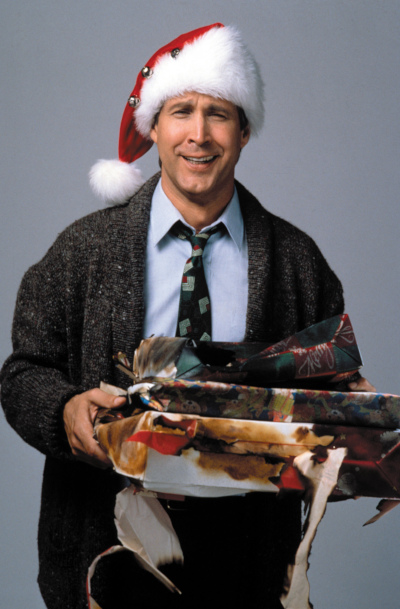

5 Fun Facts About National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation

It might seem impossible to believe, but it’s been 30 years since the Griswolds first celebrated Christmas on the big screen. Opening on December 1, 1989, National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation, where Chevy Chase’s Clark Griswold tries to put together the perfect Christmas at home despite an increasingly large number of houseguests and an ongoing series of disasters, went on to be the highest grossing film in the original Vacation series. It has become a modern holiday classic, earning multiple home video re-releases and special editions while remaining a perennially popular television attraction. Here’s a look behind the extremely bright lights at some of the fun facts behind the film.

1. Don’t You (Forget About John Hughes)

Though he’s held up as the paragon of ’80s teen films, writer/director John Hughes created a number of other films for a variety of audiences, including Mr. Mom and the pirate action film Nate and Hayes. After a start in advertising, Hughes caught on as a writer for the humor magazine National Lampoon, which would soon break into film-producing success with 1979’s National Lampoon’s Animal House. Hughes’s first story for the magazine was “Vacation ’58.” That tale of a family trip became the basis for the first Vacation film, which he wrote. He co-wrote European Vacation with Robert Klane, and then handled the screenplay for Christmas on his own. Like the original film, Christmas Vacation was based on a Hughes/Lampoon piece, “Christmas ’59.”

2. Honey, Who Are the Kids?

The Griswolds are, of course, the central family of the Vacation films. Dad Clark and long-suffering wife Ellen have been played by Chevy Chase and Beverly D’Angelo since the beginning. However, son Rusty and daughter Audrey were played by different actors in each of the five theatrical films. The original Vacation featured Anthony Michael Hall and Dana Barron in the roles. They were followed by, respectively, Jason Lively and Dana Hill in European Vacation, Johnny Galecki and Juliette Lewis in Christmas Vacation, and Ethan Embry and Marisol Nichols in Vegas Vacation. In the 2015 reboot, simply titled Vacation, adult Rusty is played by Ed Helms and adult Audrey is played by Leslie Mann; however, in a great sight gag, all of the other previous actors appear in childhood photos. Barron did play Audrey again in the 2003 made-for-TV film National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation 2: Cousin Eddie’s Island Adventure, and yes, that really happened.

3. The Music Is Missing (on CD)

Mele Kalikimaka by Bing Crosby (Uploaded to YouTube by Bing Crosby / Universal Music Group)

Two oddities surround the soundtrack and music used in the film. The first is that no soundtrack album was ever released, which is strange when you consider that holiday soundtracks can be perennial sellers regardless of the success or failure of a film; no one’s quite sure why, although a limited edition CD pressing was sold in the 1990s at Six Flags Magic Mountain (which was used as Wally World in the first film) and those discs fetch more than $100 online today. The other is that Christmas is the sole film in the franchise to not use an iteration of Lindsey Buckingham’s “Holiday Road.” A replacement theme, “Christmas Vacation,” was written by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, and performed by Mavis Staples. Other prominently featured songs include “Mele Kalikimaka (Hawaiian Christmas Song)” by Bing Crosby and The Andrews Sisters, “The Spirit of Christmas” by Ray Charles, and “Here Comes Santa Claus” by Gene Autry. The instrumental score was done by Angelo Badalamenti, the prolific composing legend most known for his work with director David Lynch.

4. Scene Stealing, the Quaid Way

Randy Quaid’s Cousin Eddie is only in the first Vacation film for a few minutes, but he made a deep impression. After missing the first sequel, Eddie and Catherine (Miriam Flynn) came back, and Eddie in particular provided a number of memorable moments. In an oral history of the film conducted by Rolling Stone, Flynn recounted how she and Quaid got into character; she said, “Randy and I always said that all you have to do is put those clothes on us and we were ready to go. Once I remember the costume person said to me, “Randy thinks it’d be funny to have his underwear show through his white pants. What if you did that too?” And I went, “Um, no. That will be just Randy.” In the same article, Chase said, “I loved working with Randy on all of the Vacation movies . . . He just gets right into it. When we’re in the grocery store and he gets that huge 100 pound bag of dog food and slams it down. I don’t think anybody wrote that. That was just Randy reaching out and grabbing it.” Quaid’s Eddie is so iconic of a comedy role that he inspired an exclusive Build-A-Bear Workshop plush of his character this year, complete with signature hat and robe.

5. He’s Chevy Chase, and She’s Not

Of course, the whole franchise doesn’t work without Chevy Chase and Beverly D’Angelo. The duo’s effortless chemistry comes with a real-life friendship that’s been on display not just in films, but in numerous interviews and D’Angelo’s appearance at The Comedy Central Roast of Chevy Chase. Chase was the first of the original SNL cast members to break out in film, putting together a string of comedy successes that included Foul Play, Caddyshack, and Fletch. In fact, the Vacation series would go on to include a number of past and future SNL players (as well as Second City and SCTV alums); in addition to Chase and Quaid, there’s Anthony Michael Hall (who became the youngest cast member ever two years after Vacation), John Candy, Eugene Levy, Brian Doyle-Murray, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Julia Sweeney, and Fred Willard. Chase has continued to work in comedy for decades, including more recent successes like Community and the Hot Tub Time Machine movies.

D’Angelo has had an amazingly diverse career. After working as an artist for the Hanna-Barbera Studios and singing back-up with The Hawks (before they became The Band), she worked on both Broadway and television before breaking into film with a part in Annie Hall. She’s worked practically non-stop in film and television, appearing in series like Entourage and Insatiable. D’Angelo also has CMA Award for Album of the Year, as she both portrayed and sang as Patsy Cline in the 1980 film Coal Miner’s Daughter.

It’s hard to define what makes a classic, or at least beloved, film. The Vacation movies thrive because they work on simple, relatable premise: families like to spend time together, but it can still be a chore. You can also add Murphy’s Law: if anything can go wrong, it will. Chase imbues his Clark Griswold with a fanatic, almost hopeless, optimism that he’s going to make everyone have fun, even if it kills him. Chase’s genius at physical comedy and unhinged line deliveries play terrifically off of D’Angelo and everyone else around them. What results are outrageous situations that still carry an element of truth. Viewers can say, “That could be my family,” and mean it. It can make the most hardened cynic want to gather around the tree and sing carols (provided of course that the tree is squirrel-free and not, well, on fire).

Featured image: PictureLux / The Hollywood Archive / Alamy Stock Photo