It’s 50 Years of Franklin, Charlie Brown!

He never kicked that football. His baseball team was historically terrible. He got nothing but rocks for Trick-or-Treating. And he was not a noted director of Christmas pageants. Yet Charlie Brown can count one absolute triumph on his resume. Fifty years ago today, Charlie Brown made a friend. That friend, Franklin, broke barriers, infuriated segments of the readership, and remains a radical statement from a tumultuous time. Why? Franklin was the first African-American character in Peanuts.

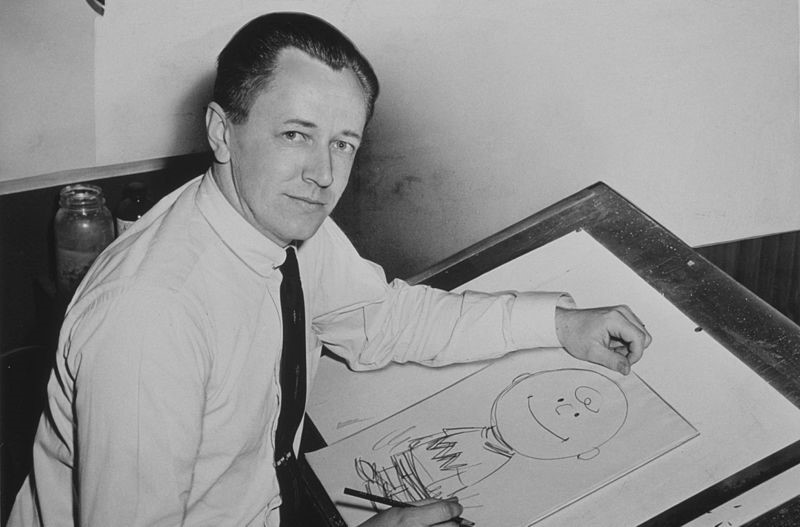

Franklin’s origins began in a series of correspondence between Peanuts creator Charles M. Schulz and a school teacher from California named Harriet Glickman in the spring of 1968. Schulz by that time was well established, achieving fame with Peanuts in the years since its launch in 1950; The Saturday Evening Post visited him in 1957, taking a look at the comics’ popularity and merchandising strength. The strip had caught notice not only for its humor and Schulz’s seemingly simple but sophisticated art, but for the creator’s injection of philosophy and social awareness.

Glickman, a mother of three, first wrote Schulz in April of 1968 after considering what positive actions people could take in society following the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. earlier that month. She asked Schulz to consider adding African-American children to the cast, noting herself that it might be a difficult proposition considering the tenor of many institutions, including newspapers, syndication interests, and advertisers. Schulz responded that he and other cartoonists would love to, but was primarily concerned that he might seem “patronizing to our Negro friends.”

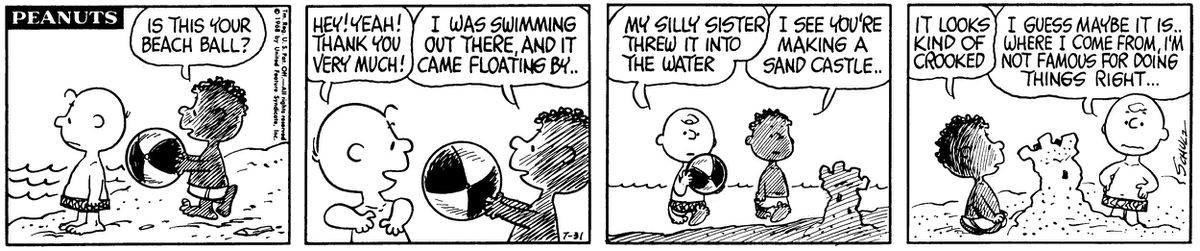

Glickman and Schulz continued to write, with Glickman offering to solicit the opinion of other parents and Schulz weighing his options. By July 1st, he’d written Glickman and told her to keep an eye out for the July 31st strip. That would be the day that Charlie Brown met a new friend on the beach. That friend turned out to be Franklin.

Charlie Brown first meets Franklin while searching for a lost beach ball. Franklin finds it and returns it, and the pair teams up to build a sandcastle. It was simple, sweet, and completely radical. In an interview collected in the book Charles M. Schulz: Conversations, Schulz recalled a “southern editor” who wrote him and said, “I don’t mind you having a black character, but please don’t show them in school together.” Schulz ignored him. In fact, Franklin would later be shown in school, seated in most classroom shots in front of Peppermint Patty.

Schulz recounted some further negative reactions in an interview with Michael Barrier in 1988. Schulz said, “I finally put Franklin in, and there was one strip where Charlie Brown and Franklin had been playing on the beach, and Franklin said, ‘Well, it’s been nice being with you, come on over to my house some time.’ Again, they didn’t like that.” Schulz also recalled a discussion with Larry Rutman, who at the time ran King Features Syndicate (which distributed Peanuts to newspapers). Schulz said, “I remember telling Larry at the time about Franklin—he wanted me to change it, and we talked about it for a long while on the phone, and I finally sighed and said, “Well, Larry, let’s put it this way: Either you print it just the way I draw it or I quit. How’s that?”

Schulz seemed mindful that Franklin would be acting as a sort of representative character. Of all the cast, he’s probably the nicest to Charlie Brown, outside of Linus, and is generally depicted as warm and fair. Schulz seemed to do his best to avoid making the character a stereotype, and even lent him some extra depth and topicality by indicating that Franklin’s father was serving in Vietnam.

Franklin went on to appear regularly in the strip and in media spin-offs. His first animated appearance came in the 1972 movie, Snoopy, Come Home. He would pop up in many specials (notably in A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving in 1973) and subsequent TV series and films; he was among the characters to appear in the most recent big-screen adaptation, The Peanuts Movie, in 2015.

Over time, a number of people would recall the positive impact that Franklin had on them. Chief among them may be Jump Start cartoonist Robb Armstrong. In an interview with Renee Montagne for NPR’s Weekend Edition, Armstrong related that he already wanted to be a cartoonist, and then Franklin appeared, allowing him to see someone that looked like him. Years later, Armstrong would send Schulz a copy of his comic strip featuring a Snoopy gag, and it sparked a friendship between the two. Later, Franklin would be given the last name Armstrong (in animation; his last name never appeared in print) as a tribute to their bond.

It’s true that Franklin lacked some of the defining eccentricities of other cast members, but that didn’t stop his inclusion from being quietly revolutionary. Franklin would inspire people like Armstrong, endure as a character, and gently nudge young readers toward the notion that, as Martin Luther King Jr. famously said, the content of your character is more important than the color of your skin.