“The Hobo and the Fairy” by Jack London

Jack London’s short stories in the Post concerned adventurers, criminals, working men, society folks, and — sometimes — wild animals. In “The Hobo and the Fairy,” from 1911, London tells the heartwarming tale of a homeless man and a bright-eyed, middle class child as they form an unlikely bond on a warm October’s day.

Published on February 2, 1911

He lay on his back. So heavy was his sleep that the stamp of hoofs and cries of the drivers from the bridge that crossed the creek did not rouse him. Wagon after wagon, loaded high with grapes, passed the bridge on the way up the valley to the winery, and the coming of each wagon was like an explosion of sound and commotion in the lazy quiet of the afternoon.

But the man was undisturbed. His head had slipped from the folded newspaper and the straggling, unkempt hair was matted with the foxtails and burs of the dry grass on which it lay. He was not a pretty sight. His mouth was open, disclosing a gap in the upper row where several teeth at some time had been knocked out. He breathed stertorously, at times grunting and moaning with the pain of his sleep. Also, he was very restless, tossing his arms about, making jerky, half-convulsive movements and at times rolling his head from side to side in the bum. This restlessness seemed occasioned partly by some internal discomfort and partly by the sun that streamed down on his face, and by the flies that buzzed and lighted and crawled upon the nose and cheeks and eyelids. There was no other place for them to crawl, for the rest of the face was covered with matted beard, slightly grizzled, but greatly dirt-stained and weather-discolored.

The cheekbones were blotched with the blood congested by the debauch that was evidently being slept off. This, too, accounted for the persistence with which the flies clustered around the mouth, lured by the alcohol-laden exhalations. He was a powerfully built man, thick-necked, broad-shouldered, with sinewy wrists and toil-distorted hands. Yet the distortion was not due to recent toil, nor were the calluses other than ancient that showed under the dirt of the one palm upturned. From time to time this hand clenched tightly and spasmodically into a fist, large, heavy-boned and wicked-looking.

The man lay in the dry grass of a tiny glade that ran down to the tree-fringed bank of the stream. On each side of the glade was a fence of the old stake-and-rider type, though little of it was to be seen, so thickly was it overgrown by wild blackberry bushes, scrubby oaks and young madrofia trees. In the rear a gate through a low paling fence led to a snug, squat bungalow, built in the California Spanish style and seeming to have been compounded directly from the landscape of which it was so justly a part. Neat and trim and modestly sweet was the bungalow, redolent of comfort and repose, telling with quiet certitude of someone that knew and that had sought and found.

Through the gate and into the glade came as dainty a little maiden as ever stepped out of an illustration made especially to show how dainty little maidens may be. Eight years she might have been, and possibly a trifle more, or less. Her little mist and little black-stockinged calves showed how delicately fragile she was; but the fragility was of mould only. There was no hint of anemia in the clear, healthy complexion or in the quick, tripping step. She was a little, delicious blonde, with hair spun of gossamer gold and wide blue eyes that were but slightly veiled by the long lashes. Her expression was of sweetness and happiness; it belonged by right to any face that was sheltered in the bungalow.

She carried a parasol, which she was careful not to tear against the scrubby branches and bramble-bushes as she sought for wild poppies along the edge of the fence. They were late poppies, a third generation, which had been unable to resist the call of the warm October sun.

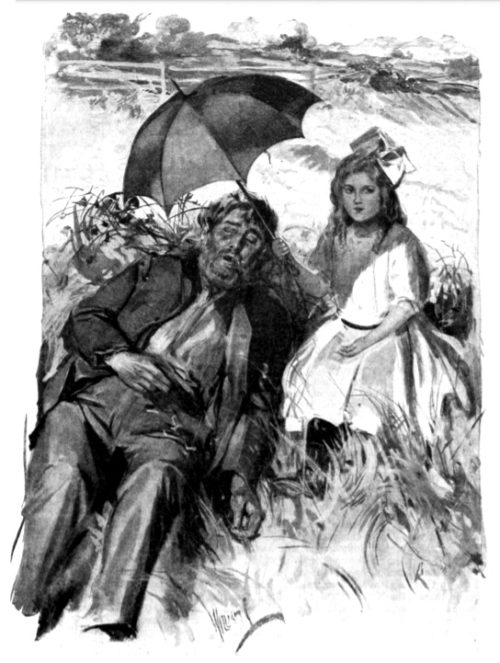

Having gathered along one fence she turned to cross to the opposite fence. Midway in the glade she came upon the tramp. Her startle was merely a startle. There was no fear in it. She stood and looked long and curiously at the forbidding spectacle and was about to turn back when the sleeper moved restlessly and rolled his head among the burs. She noted the sun on his face and the buzzing flies; her face grew solicitous and for a moment she debated with herself. Then she tiptoed to his side, interposed the parasol between him and the sun and brushed away the flies. After a time, for greater ease, she sat down beside him.

An hour passed, during which she occasionally shifted the parasol from one tired hand to the other. At first the sleeper had been restless; but, shielded from the flies and sun, his breathing became gentler and his movements ceased. Several times, however, he really frightened her. The first was the worst, coming abruptly and without warning. “How deep! How deep!” the man murmured from some profound of dream. The parasol was agitated, but the little girl controlled herself and continued her self-appointed ministrations.

Another time it was a gritting of teeth, as of some intolerable agony. So terribly did the teeth crunch and grind together that it seemed they must crash into fragments. A little later he suddenly stiffened out. The hands clenched and the face set with the savage resolution of the dream. The eyelids trembled from the shock of the fantasy, seemed about to open, but did not. Instead, the lips muttered:

“No! No! And once more, no! I won’t peach.” The lips paused, then went on. “You might as well tie me up, warden, and cut me to pieces. That’s all you can get outa me — blood. That’s all any of you-uns has ever got outa me in this hole.”

After this outburst the man slept gently on while the little girl still held the parasol aloft and looked down with a great wonder at the frowsy, unkempt creature, trying to reconcile it with the little part of life that she knew. To her ears came the cries of men, the stamp of hoofs on the bridge and the creak and groan of wagons heavy-laden. It was a breathless, California Indian-summer day. Light fleeces of cloud drifted in the azure sky, but to the west heavy cloudbanks threatened with rain. A bee droned lazily by. From farther thickets came the calls of quail and from the fields the songs of meadowlarks; and oblivious to it all slept Ross Shanklin — Ross Shanklin, the tramp and outcast, ex-convict 4379, the bitter and unbreakable one who had defied all keepers and survived all brutalities.

Texan-born, of the old pioneer stock that was always tough and stubborn, he had been unfortunate. At seventeen years of age he had been apprehended for horse-stealing. Also, he had been convicted of stealing seven horses that he had not stolen, and he had been sentenced to fourteen years’ imprisonment. This was severe under any circumstance, but with him it had been especially severe because there had been no prior convictions against him. The sentiment of the people who believed him guilty had been that two years was adequate punishment for the youth, but the county attorney, paid according to the convictions he secured, had made seven charges against him and earned seven fees, which goes to show that the county attorney valued twelve years of Ross Shanklin’s life at less than a few dollars.

Young Ross Shanklin had toiled in hell; he had escaped more than once and he had been caught and sent back to toil in other and various hells. He had been triced up and lashed till he fainted, had been revived and lashed again. He had been in the dungeon ninety days at a time. He had experienced the torment of the straitjacket. He knew what the hummingbird was. He had been farmed out as a chattel by the state to the contractors. He had been trailed through swamps by bloodhounds. Twice he had been shot. For six years on end he had cut a cord and a half of wood each day in a convict lumber camp. Sick or well, he had cut that cord and a half or paid for it under a whip-lash, knotted and pickled.

And Ross Shanklin had not sweetened under the treatment. He had sneered and cursed and defied. He had seen convicts, after the guards had manhandled them, crippled in body for life or left to maunder in mind to the end of their days. He had seen convicts, even his own cellmate, goaded to murder by their keepers, go to the gallows cursing God. He had been in a break in which eleven of his kind were shot down. He had been through a mutiny where, in the prison yard, with gatling guns trained upon them, three hundred convicts had been disciplined with pick-handles wielded by brawny guards.

He had known every infamy of human cruelty and through it all he had never been broken. He had resented and fought to the last; until, embittered and bestial, the day came when he was discharged. Five dollars were given him in payment for the years of his labor and the flower of his manhood. And he had worked little in the years that followed. Work he despised. He tramped, begged and stole, lied or threatened, as the case might warrant; and drank to besottedness whenever he got the chance.

The little girl was looking at him when he awoke. Like a wild animal, all of him was awake the instant he opened his eyes. The first he saw was the parasol, strangely obtruded between him and the sky. He did not start or move, though his whole body seemed slightly to tense. His eyes followed down the parasol handle to the tight-clutched little fingers and along the arm to the child’s face. Straight and unblinking, he looked into her eyes; and she, returning the look, was chilled and frightened by his glittering eyes, cold and harsh, withal bloodshot, and with no hint in them of the warm humanness she had been accustomed to see and feel in human eyes. They were the true prison eyes — the eyes of a man who had learned to talk little; who had forgotten almost how to talk.

“Hello!” he said finally, making no effort to change his position. “What game are you up to?” His voice was gruff, and at first it had been harsh; but it had softened queerly in a feeble attempt at forgotten kindliness.

“How do you do?” she said. “I’m not playing. The sun was on your face and mamma says one oughtn’t to sleep in the sun.”

The sweet clearness of her child’s voice was pleasant to him and he wondered why he had never noticed it in children’s voices before. He sat up slowly and stared at her. He felt that he ought to say something, but speech with him was a reluctant thing.

“I hope you slept well,” she said gravely.

“I sure did,” he answered, never taking his eyes from her, amazed at the fairness and delicacy of her. “How long was you holdin’ that contraption up over me?”

“O-oh!” she debated with herself; “a long, long time. I thought you never would wake up.”

“And I thought you was a fairy when I first seen you.”

He felt elated at his contribution to the conversation.

“No, not a fairy,” she smiled.

He thrilled in a strange numb way at the whiteness of her small, even teeth. “I was just the good Samaritan,” she added.

“I reckon I never heard of that party.” He was cudgeling his brains to keep the conversation going. Never having been at close quarters with a child since he was man-grown, he found it difficult.

“What a funny man not to know about the good Samaritan! Don’t you remember? A certain man went down to Jericho — ”

“I reckon I’ve b’en there,” he interrupted.

“I knew you were a traveler!” she cried, clapping her hands. “Maybe you saw the exact spot.”

“What spot?”

“Why, where he fell among thieves and was left half dead. And then the good Samaritan went to him and bound up his wounds, and poured in oil and wine — was that olive oil, do you think?”

He shook his head slowly.

“I reckon you got me there. Olive oil is something the dagos cooks with. I never heard it was good for busted heads.”

She considered his statement for a moment. “Well,” she announced, “we use olive oil in our cooking; so we must be dagos. I never knew what they were before. I thought it was slang.”

“And the Samaritan dumped oil on his head,” the tramp muttered reminiscently. “Seems to me I recollect a sky pilot sayin’ something about that old gent. D’ye know, I’ve been looking for him off ’n’ on all my life and never, scared up hide or hair of him. They ain’t no more Samaritans.”

“Wasn’t I one?” she asked quickly.

He looked at her steadily, with a great curiosity and wonder. Her ear, by a movement exposed to the sun, was transparent. It seemed he could almost see through it. He was amazed at the delicacy of her coloring, at the blue of her eyes, at the dazzle of the sun-touched golden hair; and he was astounded by her fragility. It came to him that she was easily broken. His eye went quickly from his huge, gnarled paw to her tiny hand, in which it seemed to him he could almost see the blood circulate. He knew the power in his muscles and he knew the tricks and turns by which men use their bodies to ill-treat men; in fact, he knew little else and his mind for the time ran in its customary channel. It was his way of measuring the beautiful strangeness of her. He calculated a grip — and not a strong one — that could grind her little fingers to pulp. He thought of fist-blows he had given to men’s heads and received on his own head, and felt that the least of them could shatter hers like an eggshell. He scanned her little shoulders and slim waist, and knew in all certitude that with his two hands he could rend her to pieces.

“Wasn’t I one?” she insisted again.

He came back to himself with a shock — or away from himself as the case happened. He was loath that the conversation should cease.

“What?” he answered. “Oh, yes; you bet you was a Samaritan, if you didn’t have no olive oil.” He remembered what his mind had been dwelling on and asked: “But ain’t you afraid?”

She looked at him as if she did not understand.

“Of — of me?” he added lamely.

She laughed merrily.

“Mamma says never to be afraid of anything. She says that if you’re good — and you think good of other people — they’ll be good too.”

“And you was thinkin’ good of me when you kept the sun off,” he marveled.

“But it’s hard to think good of bees and nasty crawly things,” she confessed.

“But there’s men that is nasty and crawly things,” he argued.

“Mamma says no. She says there’s some good in everyone.”

“I bet you she locks the house up tight at night, just the same,” he proclaimed triumphantly.

“But she doesn’t. Mamma isn’t afraid of anything. That’s why she lets me play out here alone when I want. Why, we had a robber once. Mamma got right up and found him. And what do you think! He was only a poor hungry man. And she got him plenty to eat from the pantry; and afterward she got him work to do.”

Ross Shanklin was stunned. The vista shown him of human nature was unthinkable. It had been his lot to live in a world of suspicion and hatred, of evil-believing and evil-doing. It had been his experience, slouching along village streets at nightfall, to see little children, screaming with fear, run from him to their mothers. He had even seen grown women shrink aside from him as he passed along the sidewalk.

He was aroused by the girl clapping her hands as she cried out: “I know what you are! You’re an open-air crank. That’s why you were sleeping here in the grass.”

He felt a grim desire to laugh, but repressed it.

“And that’s what tramps are — open-air cranks,” she continued. “I often wondered. Mamma believes in the open air. I sleep on the porch at night. So does she. This is our land. You must have climbed the fence. Mamma lets me when I put on my climbers — they’re bloomers, you know. But you ought to be told something. A person doesn’t know when they snore because they’re asleep. But you do worse than that. You grit your teeth. That’s bad. Whenever you are going to sleep you must think to yourself, ‘I won’t grit my teeth; I won’t grit my teeth,’ over and over, just like that; and by-and-by you’ll get out of the habit.

“All bad things are habits. And so are all good things. And it depends on us what kind our habits are going to be. I used to pucker my eyebrows — wrinkle them all up; but mamma said I must overcome that habit. She said that when my eyebrows were wrinkled it was an advertisement that my brain was wrinkled inside and that it wasn’t good to have wrinkles in the brain. Then she smoothed my eyebrows with her hand and said I must always think smooth — smooth inside and smooth outside. And, do you know, it was easy. I haven’t wrinkled my brows for ever so long. I’ve heard about filling teeth by thinking, but I don’t believe that. Neither does mamma.”

She paused, rather out of breath. Nor did he speak, Her flow of talk had been too much for him. Also, sleeping drunkenly, with open mouth, had made him very thirsty; but, rather than lose one precious moment, he endured the torment of his scorching throat. He licked his dry lips and struggled for speech.

“What is your name?” he managed at last.

“Joan.”

She looked her own question at him and it was not necessary to voice it.

“Mine is Ross Shanklin,” he volunteered, for the first time in forgotten years giving his real name.

“I suppose you’ve traveled a lot.”

“I sure have, but not as much as I might have wanted to.”

“Papa always wanted to travel, but he was too busy at the office. He never could get much time. He went to Europe once with mamma. That was before I was born. It takes money to travel.”

Ross Shanklin did not know whether to agree with this statement or not.

“But it doesn’t cost tramps much for expenses.” She took the thought away from him. “Is that why you tramp?”

He nodded and licked his lips. “Mamma says it’s too bad that men must tramp to look for work; but there’s lots of work now in the country. All the farmers in the valley are trying to get men. Have you been working?”

He shook his head, angry with himself that he should feel shame at the confession when his savage reasoning told him he was right in despising work. But this was followed by another thought. This beautiful little creature was some man’s child. She was one of the rewards of work.

“I wish I had a little girl like you,” he blurted out, stirred by a sudden consciousness of his newborn passion for paternity. “I’d work my hands off. I — I’d do anything.”

She considered his case with fitting gravity. “Then you aren’t married?”

“Nobody would have me.”

“Yes, they would — if — ”

She did not turn up her nose, but she favored his dirt and rags with a look of disapprobation he could not mistake.

“Go on!” he half shouted. “Shoot it into me! If I was washed — if I wore good clothes — if I was respectable — if I had a job and worked regular — if I wasn’t what I am.”

To each statement she nodded.

“Well, I ain’t that kind,” he rushed on. “I’m no good. I’m a tramp. I don’t want to work — that’s what. And I like dirt.”

Her face was eloquent with reproach as she said: “Then you were only making believe when you wished you had a little girl. like me?”

This left him speechless, for he knew, in all the deeps of his newfound passion, that was just what he did want.

With ready tact, noting his discomfort, she sought to change the subject.

“What do you think of God?” she asked.

“I ain’t never met Him. What do you think about Him?”

His reply was evidently angry and she was frank in her disapproval.

“You are very strange,” she said. “You get angry so easily. I never saw anybody before that got angry about God, or work, or being clean.”

“He never done anything for me,” he muttered resentfully. He cast back in quick review of the long years of toil in the convict camps and mines. “And work never done anything for me neither.”

An embarrassing silence fell.

He looked at her, numb and hungry with the stir of the father-love, sorry for his ill temper, puzzling his brain for something to say. She was looking off and away at the clouds and he devoured her with his eyes. He reached out stealthily and rested one grimy hand on the very edge of her little dress.

It seemed to him that she was the most wonderful thing in the world. The quail still called from the coverts and the harvest sounds seemed abruptly to become very loud. A great loneliness oppressed him.

“I’m — I’m no good!” he murmured huskily and repentantly.

But, beyond a glance from her blue eyes, she took no notice. The silence was more embarrassing than ever. He felt that he could give the world just to touch with his lips that hem of her dress where his hand rested, but he was afraid of frightening her. He fought to find something to say, licking his parched lips and vainly attempting to articulate something — anything.

“This ain’t Sonoma Valley,” he declared finally. “This is fairyland and you’re a fairy. Mebbe I’m asleep and dreaming! I don’t know. You and me don’t know how to talk together, because, you see, you’re a fairy and don’t know nothing but good things — and I’m a man from the bad, wicked world.”

Having achieved this much, he was left gasping for ideas like a stranded fish.

“And you’re going to tell me about the bad, wicked world,” she cried, clapping her hands. “I’m just dying to know.”

He looked at her, startled, remembering the wreckage of womanhood he had encountered on the sunken ways of life. She was no fairy. She was flesh and blood, and the possibilities of wreckage were in her as they had been in him, even when he lay at his mother’s breast. And there was in her eagerness to know.

He said lightly; “This man from the bad, wicked world ain’t going to tell you nothing of the kind. He’s going to tell you of the good things in that world. He’s going to tell you how he loved hosses when he was a shaver, and about the first boss he straddled, and the first hoss he owned. Hosses ain’t like men. They’re better. They’re clean — clean all the way through and backsgain. And, little fairy, I want to tell you one thing — there sure ain’t nothing in the world like when you’re settin’ a tired hose at the end of a long day, and when you just speak and that tired animal lifts under you willing and hustles along. Hosses! They’re my long suit. I sure dote on hosses! Yep. I used to be a cowboy once.”

She clapped her hands in the way that tore so delightfully to his heart and her eyes were dancing as she exclaimed:

“A Texas cowboy! I always wanted to see one! I heard papa say once that cowboys are bow-legged. Are you?”

“I sure was a Texas cowboy,” he answered; “but it was a long time ago. And I’m sure bow-legged. You see, you can’t ride much when you’re young and soft without getting the legs bent some. Why, I was only a three-year-old when I begun. He was a three-year-old too, fresh-broken. I led him up alongside the fence, dumb to the top rail and dropped on. He was a pinto and a real devil at bucking, but I could do anything with him. I reckon he knowed I was only a little shaver. Some hosses knows lots more’n you think.”

For half an hour Ross Shanklin rambled on with his horse reminiscences. Then came a woman’s voice.

“Joan! Joan!” it called. “Where are you, dear?”

The little girl answered; and Ross Shanklin saw a woman, clad in a soft, clinging gown, come through the gate from the bungalow.

“What have you been doing all afternoon?” the woman asked as she came up. “Talking, mamma,” the little girl replied. “I’ve had a very interesting time.” Ross Shanklin scrambled to his feet and stood watchfully and awkwardly. The little girl took the mother’s hand; and she, in turn, looked at him frankly and pleasantly, with a recognition of his humanness that was a new thing to him.

In his mind ran the thought: “The woman who ain’t afraid!” Not a hint was there of the timidity he was accustomed to see in women’s eyes; and he was quite aware of his bleary-eyed, forbidding appearance.

“How do you do?” She greeted him sweetly and naturally.

“How do you do, ma’am?” he responded, unpleasantly conscious of the huskiness and rawness of his voice.

“And did you have an interesting time too?” she smiled.

“Yes, ma’am. I sure did. I was just telling your little girl about hosses.”

“He was a cowboy once, mamma!“ she cried.

The mother smiled her acknowledgment to him and looked fondly down at the little girl.

“You’ll have to come along, dear,” the mother said. “It’s growing late.” She looked at Ross Shanklin hesitantly. “Would you care to have something to eat?”

“No, ma’am; thanking you kindly just the same. I — I ain’t hungry,”

“Then say goodby, Joan,” she said.

“Goodby.” The little girl held out her hand and her eyes lighted roguishly. “Goodby, Mr. Man from the bad, wicked world.”

To him, the touch of her hand as he pressed it in his was the capstone of the whole adventure.

“Goodby, little fairy,” he mumbled. “I reckon I got to be pain’ along.”

But he did not pull along. He stood staring after his vision until it vanished through the gate. The day seemed suddenly empty. He looked about him irresolutely, then climbed the fence, crossed the bridge and slouched along the road.

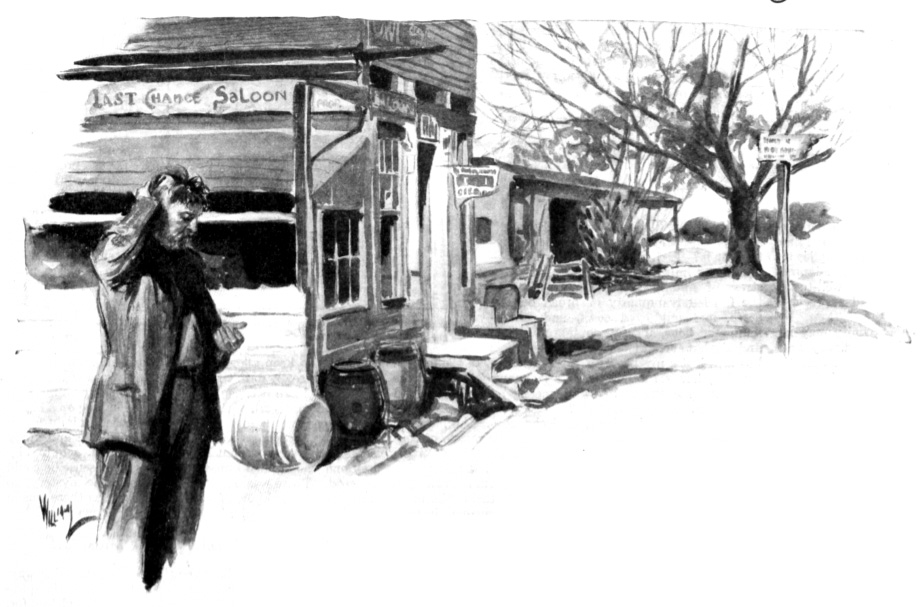

A mile farther on he aroused at the crossroads. Before him stood a saloon. He came to a stop and stared at it, licking his lips. He sank his hand into his pants pocket and pulled out a solitary dime. “God!” he muttered. “God!” Then, with dragging, reluctant feet, he went on along the road.

He came to a big farm. He knew it must be big because of the bigness of the house and the size and number of the barns and outbuildings. On the porch, in shirtsleeves, smoking a cigar, keen-eyed and middle-aged, was the farmer.

“What’s the chance for a job?” Ross Shanklin asked.

The keen eyes scarcely glanced at him.

“A dollar a day and grub,” was the answer.

Ross Shanklin swallowed and braced himself.

“I’ll pick grapes all right, or anything. But what’s the chance for a steady job? You’ve got a big ranch here. I know hosses. I was born on one. I can drive team, ride, plow, break, do anything that anybody ever done with hosses.”

“You don’t look it,” was the judgment.

“I know I don’t. Give me a chance — that’s all. I’ll prove it.”

The farmer considered, casting an anxious glance at the cloudbank into which the sun had sunk.

“I’m short a teamster and I’ll give you the chance to make good. Go and get supper with the hands.”

Ross Shanklin’s voice was very husky and he spoke with an effort:

“All right. I’ll make good. Where can I get a drink of water and wash up?”

Featured image illustrated by C.D. Williams

“The Agony Column, Part III” by Earl Derr Biggers

In the third and final part of this classic crime serial, Earl Derr Biggers concludes the winding mystery of a newspaper column and the curious stranger who haunts it. Biggers is most famous for his recurring fictional sleuth Charlie Chan as well as his popular novel Seven Keys to Baldplate, which was adapted into a Broadway stage play and later into multiple films.

Published on July 22, 1916

The fifth letter from the young man of the Agony Column arrived at the Carlton Hotel, as the reader may recall, on Monday morning, August the third. And it represented to the girl from Texas the climax of the excitement she had experienced in the matter of the murder in Ade1phi Terrace. The news that her pleasant young friend — whom she did not know — had been arrested as a suspect in the case, inevitable as it had seemed for days, came none the less as an unhappy shock. She wondered whether there was anything she could do to help. She even considered going to Scotland Yard and, on the ground that her father was a Congressman from Texas, demanding the immediate release of her strawberry man. Sensibly, however, she decided that Congressmen from Texas meant little in the life of the London police. Besides, she might have difficulty in explaining to that same Congressman how she happened to know all about a crime that was as yet unmentioned in the newspapers.

So she reread the latter portion of the fifth letter, which pictured her hero marched off ingloriously to Scotland Yard and, with a worried little sigh, went below to join her father.

In the course of the morning she made several mysterious inquiries of her parent regarding nice points of international law as it concerned murder, and it is probable that he would have been struck by the odd nature of these questions had he not been unduly excited about another matter.

“I tell you, we’ve got to get home!” he announced gloomily. “The German troops are ready at Aix-la-Chapelle for an assault on Liege. Yes, sir — they’re going to strike through Belgium! Know what that means? England in the war! Labor troubles; suffragette troubles; civil war in Ireland — these things will melt away as quickly as that snow we had last winter in Texas. They’ll go in. It would be national suicide if they didn’t.”

His daughter stared at him. She was unaware that it was the bootblack at the Carlton he was now quoting. She began to think he knew more about foreign affairs than she had given him credit for.

“Yes, sir,” he went on; “we’ve got to travel — fast. This won’t be a healthy neighborhood for noncombatants when the ruction starts. I’m going if I have to buy a liner!”

“Nonsense!” said the girl. “This is the chance of a lifetime. I won’t be cheated out of it by a silly old dad. Why, here we are, face to face with history!”

“American history is good enough for me,” he spread-eagled. “What are you looking at?”

“Provincial to the death!” she said thoughtfully. “You old dear — I love you so! Some of our statesmen over home are going to look pretty foolish now in the face of things they can’t understand. I hope you’re not going to be one of them.”

“Twaddle!” he cried. “I’m going to the steamship offices again today and argue as I never argued for a vote.” His daughter saw that he was determined; and, wise from long experience, she did not try to dissuade him. London that hot Monday was a city on the alert, a city of hearts heavy with dread. The rumors in one special edition of the papers were denied in the next and reaffirmed in the next. Men who could look into the future walked the streets with faces far from happy. Unrest ruled the town. And it found its echo in the heart of the girl from Texas as she thought of her young friend of the Agony Column “in durance vile” behind the frowning wall of Scotland Yard.

That afternoon her father appeared, with the beaming mien of the victor, and announced that for a stupendous sum he had bought the tickets of a man who was to have sailed on the steamship Saronia three days hence.

“The boat train leaves at ten Thursday morning,” he said. “Take your last look at Europe and be ready.” Three days! His daughter listened with sinking heart. Could she in three days’ time learn the end of that strange mystery, know the final fate of the man who had first addressed her so unconventionally in a public print? Why, at the end of three days he might still be in Scotland Yard, a prisoner! She could not leave if that were true — she simply could not. Almost she was on the point of telling her father the story of the whole affair, confident that she could soothe his anger and enlist his aid. She decided to wait until the next morning; and, if no letter came then —

But on Tuesday morning a letter did come and the beginning of it brought pleasant news. The beginning — yes. But the end! This was the letter:

Dear Anxious Lady: Is it too much for me to assume that you have been just that, knowing as you did that I was locked up for the murder of a captain in the Indian Army, with the evidence all against me and hope a very still small voice indeed?

Well, dear lady, be anxious no longer. I have just lived through the most astounding day of all the astounding days that have been my portion since last Thursday. And now, in the dusk, I sit again in my rooms, a free man, and write to you in what peace and quiet I can command after the startling adventure through which I have recently passed.

Suspicion no longer points to me; constables no longer eye me; Scotland Yard is not even slightly interested in me. For the murderer of Captain Fraser-Freer has been caught at last!

Sunday night I spent ingloriously in a cell in Scotland Yard. I could not sleep. I had so much to think of — you, for example, and at intervals how I might escape from the folds of the net that had closed so tightly about me. My friend at the consulate, Watson, called on me late in the evening; and he was very kind.

But there was a note lacking in his voice, and after he was gone the terrible certainty came into my mind — he believed that I was guilty after all.

The night passed, and a goodly portion of today went by — as the poets say — with lagging feet. I thought of London, yellow in the sun. I thought of the Carlton — I suppose there are no more strawberries by this time. And my waiter — that stiff-backed Prussian — is home in Deutschland now, I presume, marching with his regiment. I thought of you.

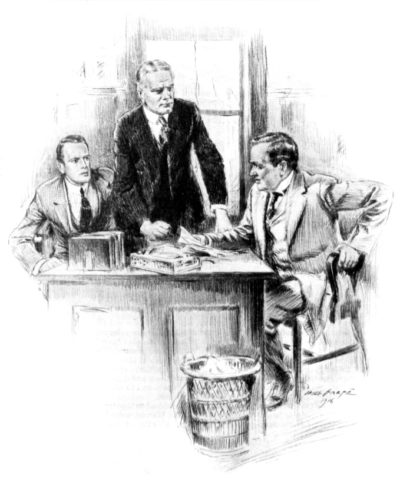

At three o’clock this afternoon they came for me and I was led back to the room belonging to Inspector Bray. When I entered, however, the inspector was not there — only Colonel Hughes, immaculate and self-possessed, as usual, gazing out the window into the cheerless stone court. He turned when I entered. I suppose I must have had a most woebegone appearance, for a look of regret crossed his face.

“My dear fellow,” he cried, “my most humble apologies! I intended to have you released last night. But, believe me, I have been frightfully busy.”

I said nothing. What could I say? The fact that he had been busy struck me as an extremely silly excuse. But the inference that my escape from the toils of the law was imminent set my heart to thumping.

“I fear you can never forgive me for throwing you over as I did yesterday,” he went on. “I can only say that it was absolutely necessary — as you shall shortly understand.”

I thawed a bit. After all, there was an unmistakable sincerity in his voice and manner.

“We are waiting for Inspector Bray,” continued the colonel. “I take it you wish to see this thing through?”

“To the end,” I answered.

“Naturally. The inspector was called away yesterday immediately after our interview with him. He had business on the Continent, I understand. But fortunately I managed to reach him at Dover and he has come back to London. I wanted him, you see, because I have found the murderer of Captain Fraser-Freer.”

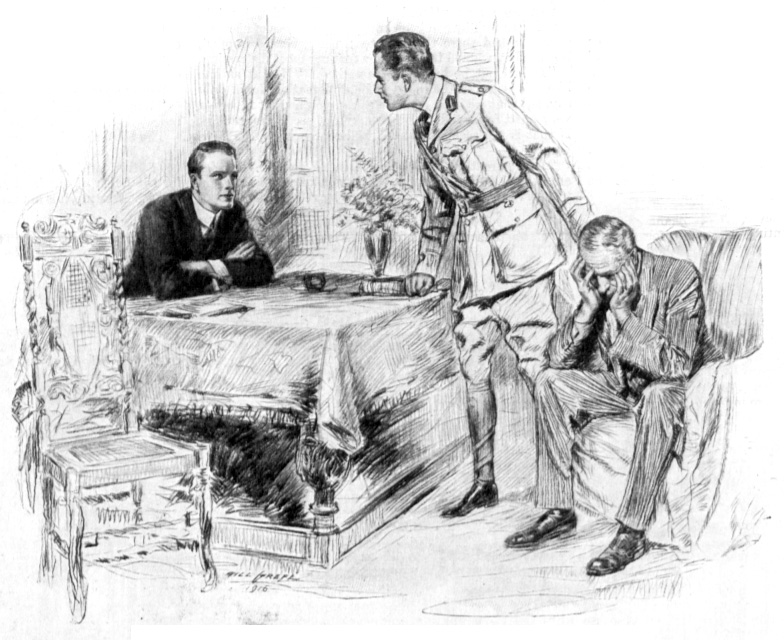

I thrilled to hear that, for from my point of view it was certainly a consummation devoutly to be wished. The colonel did not speak again. In a few minutes the door opened and Bray came in. His clothes looked as though he had slept in them; his little eyes were bloodshot. But in those eyes there was a fire I shall never forget. Hughes bowed.

“Good afternoon, inspector,” he said. “I’m really sorry I had to interrupt you as I did; but I most awfully wanted you to come back. I wanted you to know that you owe me a Homburg hat.” He went closer to the detective. “You know, I have won that wager. I have found the man who murdered Captain Fraser-Freer.”

Curiously enough, Bray said nothing. He sat down at his desk and idly glanced through the pile of mail that lay upon it. Finally he looked up and said in a weary tone:

“You’re very clever, I’m sure, Colonel Hughes.”

“Oh — I wouldn’t say that,” replied Hughes. “Luck was with me — from the first. I am really very glad to have been of service in the matter, for I am convinced that if I had not taken part in the search it would have gone hard with some innocent man.”

Bray’s big, pudgy hands still played idly with the mail on his desk. Hughes went on: “Perhaps, as a clever detective, you will be interested in the series of events which enabled me to win that Homburg hat? You have heard, no doubt, that the man I have caught is Von der Herts — ten years ago the best secret service man in the employ of the Berlin Government, but for the past few years mysteriously missing from our line of vision. We have been wondering about him — at the War Office.” The colonel dropped into a chair, facing Bray. “You know Von der Herts, of course?” he remarked casually. “Of course,” said Bray, still in that dead, tired voice. “He is the head of that crowd in England,” went on Hughes.

“Rather a feather in my cap to get him — but I mustn’t boast. Poor Fraser-Freer would have got him if I hadn’t — only Von der Herta had the luck to get the captain first.”

Bray raised his eyes. “You said you were going to tell me — “ he began. “And so I am,” said Hughes. “Captain Fraser-Freer got into rather a mess in India and failed of promotion. It was suspected that he was discontented, soured on the Service; and the Countess Sophie de Graf was set to beguile him with her charms, to kill his loyalty and win him over to her crowd.

“It was thought she had succeeded — the Wilhelmstrasse thought so — we at the War Office thought so, as long as he stayed in India.

“But when the captain and the woman came on to London we discovered that we had done him a great injustice. He let us know, when the first chance offered, that he was trying to redeem himself, to round up a dangerous band of spies by pretending to be one of them. He said that it was his mission in London to meet Von der Herts, the messages. From that column the man from Rangoon learned that he was to wear a white aster in his buttonhole, a scarab pin in his tie, a Homburg hat on his head, and meet Von der Herts at Ye Old Gambrinus Restaurant, in Regent Street, last Thursday night at ten o’clock. As we know, he made all arrangements to comply with those directions. He made other arrangements as well. Since it was out of the question for him to come to Scotland Yard, by skillful maneuvering he managed to interview an inspector of police at the Hotel Cecil. It was agreed that on Thursday night Von der Herts would be placed under arrest the moment he made himself known to the captain.”

Hughes paused. Bray still idled with his pile of letters, while the colonel regarded him gravely.

“Poor Fraser-Freer!” Hughes went on. “Unfortunately for him, Von der Herts knew almost as soon as did the inspector that a plan was afoot to trap him. There was but one course open to him: He located the captain’s lodgings, went there at seven that night, and killed a loyal and brave Englishman where he stood.”

A tense silence filled the room. I sat on the edge of my chair, wondering just where all this unwinding of the tangle was leading us.

“I had little, indeed, to work on,” went on Hughes. “But I had this advantage: The spy thought the police, and the police alone, were seeking the murderer. He was at no pains to throw me off his track, because he did not suspect that I was on it. For weeks my men had been watching the countess. I had them continue to do so. I figured that sooner or later Von der Herts would get in touch with her. I was right. And when at last I saw with my own eyes the man who must, beyond all question, be Von der Herta, I was astounded, my dear inspector. I was overwhelmed.”

“Yes?” said Bray.

“I set to work then in earnest to connect him with that night in Adelphi Terrace. All the finger marks in the captain’s study were for some reason destroyed, but I found others outside, in the dust on that seldom-used gate which leads from the garden. Without his knowing, I secured from the man I suspected the imprint of his right thumb. A comparison was startling. Next I went down into Fleet Street and luckily managed to get hold of the typewritten copy sent to the Mail bearing those four messages. I noticed that in these the letter a was out of alignment. I maneuvered to get a letter written on a typewriter belonging to my man. The a was out of alignment. Then Archibald Enwright, a renegade and waster well known to us as serving other countries, came to England. My man and he met — at Ye Old Gambrinus, in Regent Street. And finally, on a visit to the lodgings of this man who, I was now certain, was Von der Herts, under the mattress of his bed I found this knife.”

And Colonel Hughes threw down upon the inspector’s desk the knife from India that I had last seen in the study of Captain Fraser-Freer.

“All these points of evidence were in my hands yesterday morning in this room,” Hughes went on. “Still, the answer they gave me was so unbelievable, so astounding, I was not satisfied; I wanted even stronger proof. That is why I directed suspicion to my American friend here. I was waiting. I knew that at last Von der Herts realized the danger he was in. I felt that if opportunity were offered he would attempt to escape from England; and then our proofs of his guilt would be unanswerable, despite his cleverness. True enough, in the afternoon he secured the release of the countess, and together they started for the Continent. I was lucky enough to get him at Dover — and glad to let the lady go on.”

And now, for the first time, the startling truth struck me full in the face as Hughes smiled down at his victim.

“Inspector Bray,” he said, “or Von der Herts, as you choose, I arrest you on two counts: First, as the head of the Wilhelmstrasse spy system in England; second, as the murderer of Captain Fraser-Freer. And, if you will allow me, I wish to compliment you on your efficiency.”

Bray did not reply for a moment. I sat numb in my chair. Finally the inspector looked up. He actually tried to smile.

“You win the hat,” he said, “but you must go to Homburg for it. I will gladly pay all expenses.”

“Thank you,” answered Hughes. “I hope to visit your country before long; but I shall not be occupied with hats. Again I congratulate you. You were a bit careless, but your position justified that. As head of the department at Scotland Yard given over to the hunt for spies, precaution doubtless struck you as unnecessary. How unlucky for poor Fraser-Freer that it was to you he went to arrange for your own arrest! I got that information from a clerk at the Cecil. You were quite right, from your point of view, to kill him. And, as I say, you could afford to be rather reckless. You had arranged that when the news of his murder came to Scotland Yard you yourself would be on hand to conduct the search for the guilty man. A happy situation, was it not?”

“It seemed so at the time,” admitted Bray; and at last I thought I detected a note of bitterness in his voice.

“I’m very sorry — really,” said Hughes. “Today, or tomorrow at the latest, England will enter the war. You know what that means, Von der Herts. The Tower of London — and a firing squad!”

Deliberately he walked away from the inspector, and stood facing the window. Von der Herts was fingering idly that Indian knife which lay on his desk. With a quick, hunted look about the room, he raised his hand; and before I could leap forward to stop him he had plunged the knife into his heart.

Colonel Hughes turned round at my cry, but even at what met his eyes now that Englishman was imperturbable.

“Too bad!” he said. “Really too bad! The man had courage and, beyond all doubt, brains. But — this is most considerate of him. He has saved me such a lot of trouble.”

The colonel effected my release at once; and he and I walked down Whitehall together in the bright sun that seemed so good to me after the bleak walls of the Yard. Again he apologized for turning suspicion my way the previous day; but I assured him I held no grudge for that.

“One or two things I do not understand,” I said. “That letter I brought from Interlaken

“Simple enough,” he replied. “Enwright — who, by the way, is now in the Tower — wanted to communicate with Fraser-Freer, who he supposed was a loyal member of the band. Letters sent by post seemed dangerous. With your kind assistance he informed the captain of his whereabouts and the date of his imminent arrival in London. Fraser-Freer, not wanting you entangled in his plans, eliminated you by denying the existence of this cousin — the truth, of course.”

“Why,” I asked, “did the countess call on me to demand that I alter my testimony?”

“Bray sent her. He had rifled Fraser-Freer’s desk and he held that letter from Enwright. He was most anxious to fix the guilt upon the young lieutenant’s head. You and your testimony as to the hour of the crime stood in the way. He sought to intimidate you with threats — ”

“But — ”

“I know — you are wondering why the countess confessed to me next day. I had the woman in rather a funk. In the meshes of my rapid-fire questioning she became hopelessly involved. This was because she was suddenly terrified; she realized I must have been watching her for weeks, and that perhaps Von der Herta was not so immune from suspicion as he supposed. At the proper moment I suggested that I might have to take her to Inspector Bray. This gave her an idea. She made her fake confession to reach his side; once there, she warned him of his danger and they fled together.”

We walked along a moment in silence. All about us the lurid special editions of the afternoon were flaunting their predictions of the horror to come. The face of the colonel was grave.

“How long had Von der Herts held his position at the Yard’?” I asked.

“For nearly five years,” Hughes answered. “It seems incredible,” I murmured.

“So it does,” he answered; “but it is only the first of many incredible things that this war will reveal. Two months from now we shall all have forgotten it in the face of new revelations far more unbelievable.” He sighed. “If these men about us realized the terrible ordeal that lies ahead! Misgoverned; unprepared — I shudder at the thought of the sacrifices we must make, many of them in vain. But I suppose that somehow, someday, we shall muddle through.”

He bade me good-by in Trafalgar Square, saying that he must at once seek out the father and brother of the late captain, and tell them the news — that their kinsman was really loyal to his country.

“It will come to them as a ray of light in the dark–Lmy news,” he said. “And now, thank you once again.”

We parted and I came back here to my lodgings. The mystery is finally solved, though in such a way it is difficult to believe that it was anything but a nightmare at any time. But solved none the less; and I should be at peace, except for one great black fact that haunts me, will not let me rest. I must tell you, dear lady — And yet I fear it means the end of everything. If only I can make you understand!

I have walked my floor, deep in thought, in puzzlement, in indecision. Now I have made up my mind.. There is no other way — I must tell you the truth.

Despite.the fact that Bray was Von der Herts; despite the fact that he killed himself at the discovery — despite this and that, and everything Bray did not kill Captain Fraser-Freer!,

On last Thursday evening, at a little after seven o’clock, I myself climbed the stairs, entered the captain’s rooms, picked up that knife from his desk, and stabbed him just above the heart!

What provocation I was under, what stern necessity moved me — all this you must wait until tomorrow to know. I shall spend another anxious day preparing my defense, hoping that through some miracle of mercy you may forgive me — understand that there was nothing else I could do.

Do not judge, dear lady, until you know everything — until all my evidence is in your lovely hands.

YOURS, IN ALL HUMILITY

The first few paragraphs of this the sixth and next to the last letter from the Agony Column man had brought a smile of relief to the face of the girl who read. She was decidedly glad to learn that her friend no longer languished back of those gray walls on Victoria Embankment. With excitement that increased as she went along, she followed Colonel Hughes as — in the letter — he moved nearer and nearer his denouement, until finally his finger pointed to Inspector Bray sitting guilty in his chair. This was an eminently satisfactory solution, and it served the inspector right for locking up her friend. Then, with the suddenness of a bomb from a Zeppelin, came, at the end, her strawberry man’s confession of guilt. He was the murderer, after all! He admitted it! She could scarcely believe her eyes.

Yet there it was, in ink as violet as those eyes, on the note paper that had become so familiar to her during the thrilling week just past. She read it a second time, and yet a third. Her amazement gave way to anger; her cheeks flamed. Still — he had asked her not to judge until all his evidence was in. This was a reasonable request surely, and she could not in fairness refuse to grant it.

So began an anxious day, not only for the girl from Texas but for all London as well. Her father was bursting with new diplomatic secrets recently extracted from his bootblack adviser. Later, in Washington, he was destined to be a marked man because of his grasp of the situation abroad. No one suspected the bootblack, the power behind the throne; but the gentleman from Texas was destined to think of that able diplomat many times, and to wish that he still had him at his feet to advise him.

“War by midnight sure!” he proclaimed on the morning of this fateful Tuesday. “I tell you, Marian, we’re lucky to have our tickets on the Saronia. Five thousand dollars wouldn’t buy them from me today! I’ll be a happy man when we go aboard that liner day after tomorrow.”

Day after tomorrow! The girl wondered. At any rate, she would have that last letter then — the letter that was to contain whatever defense her young friend could offer to explain his dastardly act. She waited eagerly for that final epistle.

The day dragged on, bringing at its close England’s entrance into the war; and the Carlton bootblack was a prophet not without honor in a certain Texas heart. And on the following morning there arrived a letter which was torn open by eager, trembling fingers. The letter spoke:

Dear Lady Judge: This is by far the hardest to write of all the letters you have had from me. For twenty-four hours I have been planning it. Last night I walked on the Embankment while the hansoms jogged by and the lights of the tramcars danced on Westminster Bridge just as the fireflies used to in the garden back of our house in Kansas. While I walked I planned. Today, shut up in my rooms, I was also planning. And yet now, when I sit down to write, I am still confused; still at a loss where to begin and what to say, once I have begun.

At the close of my last letter I confessed to you that it was I who murdered Captain Fraser-Freer. That is the truth. Soften the blow as I may, it all comes down to that. The bitter truth!

Not a week ago — last Thursday night at seven — I climbed our dark stairs and plunged a knife into the heart of that defenseless gentleman. If only I could point out to you that he had offended me in some way; if I could prove to you that his death was necessary to me, as it really was to Inspector Bray — then there might be some hope of your ultimate pardon. But, alas! he had been most kind to me — kinder than I have allowed you to guess from my letters. There was no actual need to do away with him. Where shall I look for a defense?

At the moment the only defense I can think of is simply this — the captain knows I killed him!

Even as I write this, I hear his footsteps above me, as I heard them when I sat here composing my first letter to you. He is dressing for dinner. We are to dine together at Romano’s.

And there, my lady, you have finally the answer to the mystery that has — I hope — puzzled you. I killed my friend the captain in my second letter to you, and all the odd developments that followed lived only in my imagination as I sat here beside the green-shaded lamp in my study, plotting how I should write seven letters to you that would, as the novel advertisements say, grip your attention to the very end. Oh, I am guilty — there is no denying that! And, though I do not wish to ape old Adam and imply that I was tempted by a lovely woman, a strict regard for the truth forces me to add that there is also guilt upon your head. How so? Go back to that message you inserted in the Daily Mail: “The grapefruit lady’s great fondness for mystery and romance — ”

You did not know it, of course; but in those words you passed me a challenge I could not resist; for making plots is the business of life — more, the breath of life — to the. I have made many; and perhaps you have followed some of them, on Broadway. Perhaps you have seen a play of mine announced for early production in London. There was mention of it in the program at the Palace. That was the business which kept me in England. The project has been abandoned now and I am free to go back home.

Thus you see that when you granted me the privilege of those seven letters you played into my hands. So, said I, she longs for mystery and romance. Then, by the Lord Harry, she shall have them!

And it was the tramp of Captain Fraser-Freer’s boots above my head that showed me the way. A fine, stalwart, cordial fellow — the captain — who has been very kind to me since I presented my letter of introduction from his cousin, Archibald Enwright. Poor Archie! A meek, correct little soul, who would be horrified beyond expression if he knew that of him I had made a spy and a frequenter of Limehouse!

The dim beginnings of the plot were in my mind when I wrote that first letter, suggesting that all was not regular in the matter of Archie’s note of introduction. Before I wrote my second, I knew that nothing but the death of Fraser-Freer would do me. I recalled that Indian knife I had seen upon his desk, and from that moment he was doomed. At that time I had no idea how I should solve the mystery. But I had read and wondered at those four strange messages in the Mail, and I resolved that they must figure in the scheme of things.

The fourth letter presented difficulties until I returned from dinner that night and saw a taxi waiting before our quiet house. Hence the visit of the woman with the lilac perfume. I am afraid the Wilhelmstrasse would have little use for a lady spy who advertised herself in so foolish a manner. Time for writing the fifth letter arrived. I felt that I should now be placed under arrest. I had a faint little hope that you would be sorry about that. Oh, I’m a brute, I know! Early in the game I had told the captain of the cruel way in which I had disposed of him. He was much amused; but he insisted, absolutely, that he must be vindicated before the close of the series, and I was with him there. He had been so bully about it all! A chance remark of his gave me my solution. He said he had it on good authority that the chief of the Czar’s bureau for capturing spies in Russia was himself a spy. And so — why not a spy in Scotland Yard? I assure you, I am most contrite as I set all this down here. You must remember that when I began my story there was no idea of war. Now all Europe is aflame; and in the face of the great conflict, the awful suffering to come, I and my little plot begin to look — well, I fancy you know just how we look.

Forgive me. I am afraid I can never find the words to tell you how important it seemed to interest you in my letters — to make you feel that I am an entertaining person worthy of your notice. That morning when you entered the Carlton breakfast room was really the biggest in my life. I felt as though you had brought with you through that doorway — But I have no right to say it. I have the right to say nothing save that now — it is all left to you. If I have offended, then I shall never hear from you again.The captain will be here in a moment. It is near the hour set and he is never late. He is not to return to India, but expects to be drafted for the Expeditionary Force that will be sent to the Continent. I hope the German Army will be kinder to him than I was!My name is Geoffrey West. I live at 19 Adelphi Terrace — in rooms that look down on the most wonderful garden in London. That, at least, is real. It is very quiet there tonight, with the city and its continuous hum of war and terror seemingly a million miles away.Shall we meet at last? The answer rests entirely with you. But, believe me, I shall be anxiously waiting to know; and if you decide to give me a chance to explain — to denounce myself to you in person — then a happy man say good-by to this garden and these dim, dusty rooms and follow you to the ends of the earth — aye, to Texas itself!

Captain Fraser-Freer is coming down the stairs. Is this good-by forever, my lady? With all my soul, I hope not.

YOUR CONTRITE STRAWBERRY MAN.

Words are futile things with which to attempt a description of the feelings of the girl at the Carlton as she read this, the last letter of seven written to her through the medium of her maid, Sadie Haight. Turning the pages of the dictionary casually, one might enlist a few — for example, amazement, anger, unbelief, wonder. Perhaps, to go back to the letter a, even amusement. We may leave her with the solution to the puzzle in her hand, the Saronia little more than a day away, and a weirdly mixed company of emotions struggling in her soul.

And leaving her thus, let us go back to Adelphi Terrace and a young man exceedingly worried.

Once he knew that his letter was delivered, Mr. Geoffrey West took his place most humbly on the anxious seat. There he writhed through the long hours of Wednesday morning. Not to prolong this painful picture, let us hasten to add that at three o’clock that same afternoon came a telegram that was to end suspense. He tore it open and read:

Strawberry Man: I shall never, never forgive you. But we are sailing tomorrow on the Saronia. Were you thinking of going home soon?

MARIAN A. LARNED

Thus it happened that, a few minutes later, to the crowd of troubled Americans in a certain steamship booking office there was added a wild-eyed young man who further upset all who saw him. To weary clerks he proclaimed in fiery tones that he must sail on the Saronia. There seemed to be no way of appeasing him. The offer of a private liner would not have interested him.

He raved and tore his hair. He ranted. All to no avail. There was, in plain American, “nothing doing!”

Damp but determined, he sought among the crowd for one who had bookings on the Saronia. He could find, at first, no one so lucky; but finally he ran across Tommy Gray. Gray, an old friend, admitted when pressed that he had passage on that most desirable boat. But the offer of all the king’s horses and all the king’s gold left him unmoved. Much, he said, as he would have liked to oblige, he and his wife were determined. They would sail.

It was then that Geoffrey West made a compact with his friend. He secured from him the necessary steamer labels and it was arranged that his baggage was to go aboard the Saronia as the property of Gray.

“But,” protested Gray, “even suppose you do put this through; suppose you do manage to sail without a ticket — where will you sleep? In chains somewhere below, I fancy.”

“No matter!” bubbled West. “I’ll sleep in the dining saloon, in a lifeboat, on the lee scuppers — whatever they are. I’ll sleep in the air, without any visible support! I’ll sleep anywhere — nowhere — but I’ll sail! And as for irons — they don’t make ’em strong enough to hold me.”

At five o’clock on Thursday afternoon the Saronia slipped smoothly away from a Liverpool dock. Twenty-five hundred Americans — about twice the number of people the boat could comfortably carry — stood on her decks and cheered. Some of those in that crowd who had millions of money were booked for the steerage. All. of them were destined to experience during that crossing hunger, annoyance, discomfort. They were to be stepped on, sat on, crowded and jostled. They suspected as much when the boat left the dock. Yet they cheered!

Gayest among them was Geoffrey West, triumphant amid the confusion. He was safely aboard; the boat was on its way! Little did it trouble him that he went as a stowaway, since he had no ticket; nothing but an overwhelming determination to be on the good ship Saronia.

That night, as the Saronia stole along with all deck lights out and every porthole curtained, West saw on the dim deck the slight figure of a girl who meant much to him. She was standing staring out over the black waters; and, with wildly beating heart, he approached her, not knowing what to say, but feeling that a start must be made somehow.

“Please pardon me for addressing you,” he began. “But I want to tell you — ”

She turned, startled; and then smiled an odd little smile, which he could not see in the dark.

“I beg your pardon,” she said. “I haven’t met you, that I recall

“I know,” he answered. “That’s going to be arranged tomorrow. Mrs. Tommy Gray says you crossed with them — ”

“Mere steamer acquaintances,” the girl replied coldly.

Of course! But Mrs. Gray is a darling — she’ll fix that all right. I just want to say, before tomorrow comes — ”

“Wouldn’t it be better to wait?”

“I can’t! I’m on this ship without a ticket. I’ve got to go down in a minute and tell the purser that. Maybe he’ll throw me overboard; maybe he’ll lock me up. I don’t know what they do with people like me. Maybe they’ll make a stoker of me. And then I shall have to stoke, with no chance of seeing you again. So that’s why I want to say now — I’m sorry I have such a keen imagination. It carried me away — really it did! I didn’t mean to deceive you with those letters; but, once I got started You know, don’t you, that I love you with all my heart? From the moment you came into the Carlton that morning I

“Really — Mr. — Mr. — ”

“West — Geoffrey West. I adore you! What can I do to prove it? I’m going to prove it — before this ship docks in the North River. Perhaps I’d better talk to your father, and tell him about the Agony Column and those seven letters — ”

“You’d better not! He’s in a terribly bad humor. The dinner was awful, and the steward said we’d be looking back to it and calling it a banquet before the voyage ends. Then, too, poor dad says he simply cannot sleep in the stateroom they’ve given him — ”

“All the better! I’ll see him at once. If he stands for me now he’ll stand for me any time! And, before I go down and beard a harsh-looking purser in his den, won’t you believe me when I say I’m deeply in love — ”

“In love with mystery and romance! In love with your own remarkable powers of invention! Really, I can’t take you seriously — ”

“Before this voyage is ended you’ll have to. I’ll prove to you that I care. If the purser lets me go free — ”

“You have much to prove,” the girl smiled. “Tomorrow — when Mrs. Tommy Gray introduces us — I may accept you — as a builder of plots. I happen to know you are good. But as — as — It’s too silly! Better go and have it out with that purser.”

Reluctantly he went. In five minutes he was back. The girl was still standing by the rail.

“It’s all right!” West said. “I thought I was doing something original, but there were eleven other people in the same fix. One of them is a billionaire from Wall Street. The purser collected some money from us and told us to sleep on the deck — if we could find room.”

“I’m sorry,” said the girl. “I rather fancied you in the role of stoker.” She glanced about her at the dim deck. “Isn’t this exciting? I’m sure this voyage is going to be filled with mystery and romance.”

“I know it will be full of romance,” West answered. “And the mystery will be — can I convince you — ”

“Hush!” broke in the girl. “Here comes father! I shall be very happy to meet you — tomorrow. Poor dad! He’s looking for a place to sleep.”

Five days later poor dad, having slept each night on deck in his clothes while the ship plowed through a cold drizzle, and having starved in a sadly depleted dining saloon, was a sight to move the heart of a political opponent. Immediately after a dinner that had scarcely satisfied a healthy Texas appetite he lounged gloomily in the deck chair which was now his stateroom. Jauntily Geoffrey West came and sat at his side.

“Mr. Larned,” he said, “I’ve got something for you.”

And, with a kindly smile, he took from his pocket and handed over a large, warm baked potato. The Texan eagerly accepted the gift.

“Where’d you get it?” he demanded, breaking open his treasure.

“That’s a secret,” West answered. “But I can get as many as I want. Mr. Larned, I can say this — you will not go hungry any longer. And there’s something else I ought to speak of. I am sort of aiming to marry your daughter.”

Deep in his potato the Congressman spoke:

“What does she say about it?”

“Oh, she says there isn’t a chance. But”

“Then look out, my boy! She’s made up her mind to have you.”

“I’m glad to hear you say that. I really ought to tell you who I am. Also, I want you to know that, before your daughter and I had met, I wrote her seven letters”

“One minute,” broke in the Texan. “Before you go into all that, won’t you be a good fellow and tell me where you got this potato?”

West nodded.

“Sure!” he said; and, leaning over, he whispered.

For the first time in days a smile appeared on the face of the older man.

“My boy,” he said, “I feel I’m going to like you. Never mind the rest. I heard all about you from your friend Gray; and as for those letters — they were the only thing that made the first part of this trip bearable. Marian gave them to me to read the night we came on board.”

Suddenly from out of the clouds a long lost moon appeared, and bathed that overcrowded ocean liner in a flood of silver. West left the old man to his potato and went to find the daughter.

She was standing in the moonlight by the rail of the forward deck, her eyes staring dreamily ahead toward the great country that had sent her forth light-heartedly for to adventure and to see. She turned as West came up.

“I have just been talking with your father,” he said. “He tells me he thinks you mean to take me, after all.”

She laughed.

“Tomorrow night,” she answered, “will be our last on board. I shall give you my final decision then.”

“But that is twenty-four hours away! Must I wait so long as that?”

“A little suspense won’t hurt you. I can’t forget those long days when I waited for your letters

“I know! But can’t you give me — just a little hint — here — tonight?”

“I am without mercy — absolutely without mercy!”

And then, as West’s fingers closed over her hand, she added softly: “Not even the suspicion of a hint, my dear — except to tell you that — my answer will be — yes.”

Featured image: “Last night I walked on the embankment while the hansoms jogged by and the lights of the tramcars danced on Westminster Bridge.” Illustrated by Will Grefé / SEPS

“The Agony Column, Part II” by Earl Derr Biggers

In part two of this classic crime serial, Earl Derr Biggers continues to weave a story of intrigue and deceit centered around a mysterious newspaper column. Biggers is most famous for his recurring fictional sleuth Charlie Chan as well as his popular novel Seven Keys to Baldplate, which was adapted into a Broadway stage play and later into multiple films.

Published on July 15, 1916

The third letter from her correspondent of the Agony Column increased in the mind of the lovely young woman at the Carlton the excitement and tension the second had created. For a long time, on the Saturday morning of its receipt, she sat in her room puzzling over the mystery of the house in Adelphi Terrace. When first she had heard that Captain Fraser-Freer, of the Indian Army, was dead of a knife wound over the heart, the news had shocked her like that of the loss of some old and dear friend. She had desired passionately the apprehension of his murderer, and had turned over and over in her mind the possibilities of white asters, a scarab pin and a Homburg hat.

Perhaps the girl longed for the arrest of the guilty man thus keenly because this jaunty young friend of hers — a friend whose name she did not know — to whom, indeed, she had never spoken — was so dangerously entangled in the affair. For, from what she knew of Geoffrey West, from her casual glance in the restaurant and, far more, from his letters, she liked him extremely.

And now came his third letter, in which he related the connection of that hat, that pin and those asters with the column in the Mail which had first brought them together. As it happened, she, too, had copies of the paper for the first four days of the week. She went to her sitting room, unearthed these copies, and — gasped! For from the column in Monday’s paper stared up at her the cryptic words to Rangoon concerning asters in a garden at Canterbury. In the other three issues as well, she found the identical messages her strawberry man had quoted. She sat for a long time deep in thought; sat, in fact, until at her door came the enraged knocking of a hungry parent who had been waiting a full hour in the lobby below for her to join him at breakfast.

“Come, come!” boomed her father, entering at her invitation. “Don’t sit here all day mooning. I’m hungry if you’re not.”

With quick apologies she made ready to accompany him downstairs. Firmly, as she planned their campaign for the day, she resolved to put from her mind all thought of Adelphi Terrace. How well she succeeded may be judged from a speech made by her father that night just before dinner:

“Have you lost your tongue, Marian? You’re as uncommunicative as a newly elected officeholder. If you can’t get a little more life into these expeditions of ours we’ll pack up and head for home.”

She smiled, patted his shoulder, and promised to improve. But he appeared to be in a gloomy mood.

“I believe we ought to go, anyhow,” he went on. “In my opinion this war is going to spread like a prairie fire. The Kaiser got back to Berlin yesterday. He’ll sign the mobilization orders today as sure as fate. For the past week, on the Berlin Bourse, Canadian Pacific stock has been dropping. That means they expect England to come in.”

He gazed darkly into the future. It may seem that, for an American statesman, he had an unusual grasp of European politics. This is easily explained by the fact that he had been talking with the bootblack at the Carlton Hotel.

“Yes,” he said with sudden decision, “I’ll go down to the steamship offices early Monday morning — ”

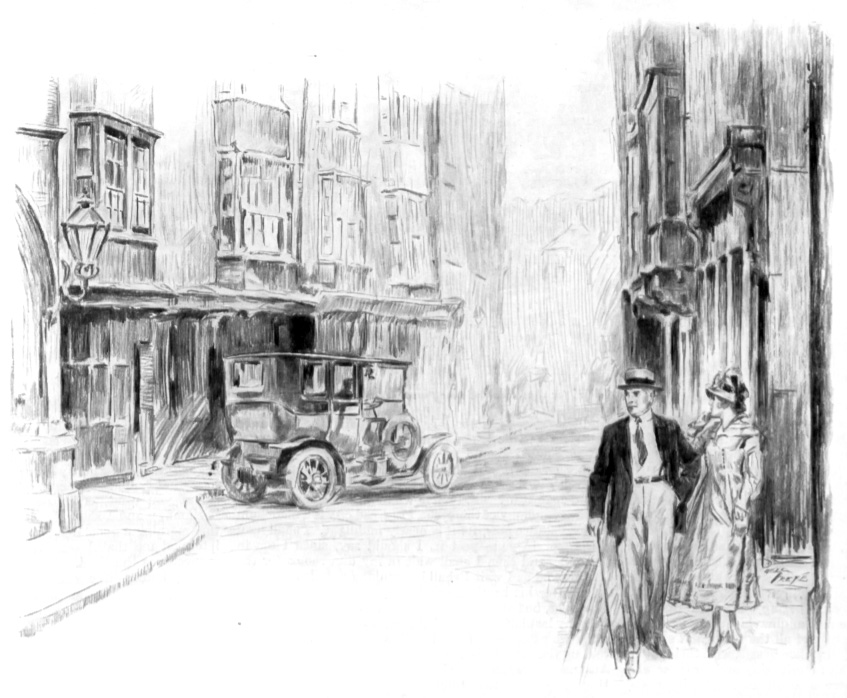

His daughter heard these words with a sinking heart. She had a most unhappy picture of herself boarding a ship and sailing out of Liverpool or Southampton, leaving the mystery that so engrossed her thoughts forever unsolved. Wisely she diverted her father’s thoughts toward the question of food. She had heard, she said, that Simpson’s, in the Strand, was an excellent place to dine. They would go there, and walk. She suggested a short detour that would carry them through Adelphi Terrace. It seemed she had always wanted to see Adelphi Terrace.

As they passed through that silent street she sought to guess, from an inspection of the grim, forbidding house fronts, back of which lay the lovely garden, the romantic mystery. But the houses were so very much dike one another. Before one of them, she noted, a taxi waited.

After dinner her father pleaded for a music hall as against what he called “some highfaluting, teacup English play.” He won. Late that night, as they rode back to the Carlton, special editions were being proclaimed in the streets. Germany was mobilizing!

The girl from Texas retired, wondering what epistolary surprise the morning would bring forth. It brought forth this:

Dear Daughter of the Senate:

Or is it Congress? I could not quite decide. But surely in one or the other of those august bodies your father sits when he is not at home in Texas or viewing Europe through his daughter’s eyes. One look at him and I had gathered that.

But Washington is far from London, isn’t it? And it is London that interests us most — though father’s constituents must not know that. It is really a wonderful, an astounding city, once you have got the feel of the tourist out of your soul. I have been reading the most enthralling essays on it, written by a newspaper man who first fell desperately in love with it at seven — an age when the whole glittering town was symbolized for him by the fried fish shop at the corner of the High Street. With him I have been going through its gray and furtive thoroughfares in the dead of night, and sometimes we have kicked an ash barrel and sometimes a romance. Someday I might show that London to you — guarding you, of course, from the ash barrels, if you are that kind. On second thoughts, you aren’t.

But I know that it is of Adelphi Terrace and a late captain in the Indian Army that you want to hear now. Yesterday, after my discovery of those messages in the Mail and the call of Captain Hughes, passed without incident. Last night I mailed you my third letter, and after wandering for a time amid the alternate glare and gloom of the city, I went back to my rooms and smoked on my balcony while about me the inmates of six million homes sweltered in the heat.

Nothing happened. I felt a bit disappointed, a bit cheated, as one might feel on the first night spent at home after many successive visits to exciting plays. Today, the first of August, dawned, and still all was quiet. Indeed, it was not until this evening that further developments in the sudden death of Captain Fraser-Freer arrived to disturb me. These developments are strange ones surely, and I shall hasten to relate them.

I dined tonight at a little place in Soho. My waiter was Italian, and on him I amused myself with the Italian in Ten Lessons of which I am foolishly proud. We talked of Fiesole, where he had lived. Once I rode from Fiesole down the hill to Florence in the moonlight. I remember endless walls on which hung roses, fresh and blooming. I remember a gaunt nunnery and two gray-robed sisters clanging shut the gates. I remember the searchlight from the military encampment, playing constantly over the Arno and the roofs — the eye of Mars that, here in Europe, never closes. And always the flowers nodding above me, stooping now and then to brush my face. I came to think that at the end Paradise, and not a second-rate hotel, was waiting. One may still take that ride, I fancy. Some day — some day —

I dined in Soho. I came back to Adelphi Terrace in the hot, reeking August dusk, reflecting that the mystery in which I was involved was, after a fashion, standing still. In front of our house I noticed a taxi waiting. I thought nothing of it as I entered the murky hallway and climbed the familiar stairs. My door stood open. It was dark in my study, save for the reflection of the lights of London outside. As I crossed the threshold there came to my nostrils the faint, sweet perfume of lilacs. There are no lilacs in our garden, and if there were it is not the season. No, this perfume had been brought there by a woman — a woman who sat at my desk and raised her head as I entered.

“You will pardon this intrusion,” she said in the correct, careful English of one who has learned the speech from a book. “I have come for a brief word with you — then I shall go.”

I could think of nothing to say. I stood gaping like a schoolboy.

“My word,” the woman went on, “is in the nature of advice. We do not always like those who give us advice. None the less, I trust that you will listen.”

I found my tongue then.

“I am listening,” I said stupidly. “But first — light.” And I moved toward the matches on the mantelpiece.

Quickly the woman rose and faced me. I saw then that she wore a veil — not a heavy veil, but a fluffy, attractive thing that was yet sufficient to screen her features from me.

“I beg of you,” she cried, “no light!” And as I paused, undecided, she added, in a tone which suggested lips that pout: “It is such a little thing to ask — surely you will not refuse.”

I suppose I should have insisted. But her voice was charming, her manner perfect, and that odor of lilacs reminiscent of a garden I knew long ago, at home.

“Very well,” said I.

“Oh — I am grateful to you,” she answered. Her tone changed. “I understand that, shortly after seven o’clock last Thursday evening, you heard in the room above you the sounds of a struggle. Such has been your testimony to the police?”

“It has,” said I.

“Are you quite certain as to the hour?” I felt that she was smiling at me. “Might it not have been later — or earlier?”

“I am sure it was just after seven,” I replied. “I’ll tell you why: I had just returned from dinner and while I was unlocking the door Big Ben on the House of Parliament struck — “

She raised her hand.

“No matter,” she said, and there was a touch of irony in her voice. “You are no longer sure of that. Thinking it over, you have come to the conclusion that it may have been barely six-thirty when you heard the noise of a struggle.”

“Indeed?” said I. I tried to sound sarcastic, but I was really too astonished by her tone.

“Yes — indeed!” she replied. “That is what you will tell Inspector Bray when next you see him. ‘It may have been six-thirty,’ you will tell him. ‘I have thought it over and I am not certain.”

“Even for a very charming lady,” I said, “I cannot misrepresent the facts in a matter so important. It was after seven — ”

“I am not asking you to do a favor for a lady,” she replied. “I am asking you to do a favor for yourself. If you refuse the consequences may be most unpleasant.”

“I’m rather at a loss — ” I began.

She was silent for a moment. Then she turned and I felt her looking at me through the veil.

“Who was Archibald Enright?” she demanded. My heart sank. I recognized the weapon in her hands. “The police,” she went on, “do not yet know that the letter of introduction you brought to the captain was signed by a man who addressed Fraser-Freer as Dear Cousin, but who is completely unknown to the family. Once that information reaches Scotland Yard, your chance of escaping arrest is slim.

“They may not be able to fasten this crime upon you, but there will be complications most distasteful. One’s liberty is well worth keeping — and then, too, before the case ends, there will be wide publicity — ”

“Well?” said I.

“That is why you are going to suffer a lapse of memory in the matter of the hour at which you heard that struggle. As you think it over, it is going to occur to you that it may have been six-thirty, not seven. Otherwise — ”

“Go on.”