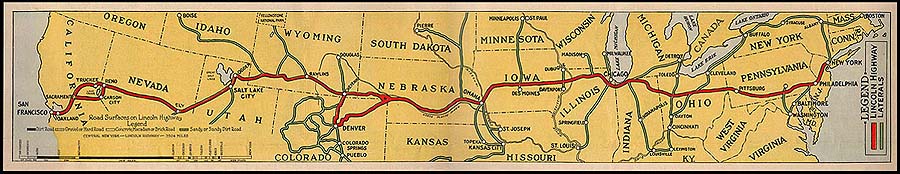

Thirteen years before Route 66 opened, the Lincoln Highway became the nation’s first transcontinental thoroughfare, stretching from New York City to San Francisco.

At the turn of the 20th century, traveling across country by automobile didn’t make much sense. Paved roads didn’t exist beyond city limits and, even then, usually only in the commercial areas of larger cities. There were no gas stations, restaurants, or motels on the roads between communities either. If your vehicle got stuck in the mud or broke down, you had to rely on someone coming along to help. Because of this, most travelers still found it easier to take the train.

Headlight mogul Carl G. Fisher realized that if it were more practical, people would choose driving themselves over a train’s timetable, and that would lead to more automobile sales. In 1912 — the year after he held the first Indy 500 on his brick-paved Indiana Motor Speedway — Fisher began planning what would become America’s first transcontinental highway, a gravel road connecting Times Square in New York City to the upcoming 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. He called it the Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway.

The name didn’t last, but stretches of the Lincoln Highway, redesignated to honor America’s 16th president, still exist today in states like Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Ohio. According to Russell S. Rein, field secretary of the Lincoln Highway Association (LHA), you can use the map on the association’s website to retrace the route and even track whether you’re on its first, second or third alignments. Rein says driving the Lincoln Highway offers a look at how automotive travel evolved over the decades.

The Original Lincoln Highway

Funding and logistics impacted the original 1913 route. Since the U.S. Department of Transportation didn’t exist at that time, Fisher turned to auto manufacturers and affiliated industries, like concrete, for financial contributions. With a limited budget, cutting a new road through the country didn’t make sense, so Fisher and his newly formed LHA connected existing roads through as many major cities as possible to create a transcontinental route.

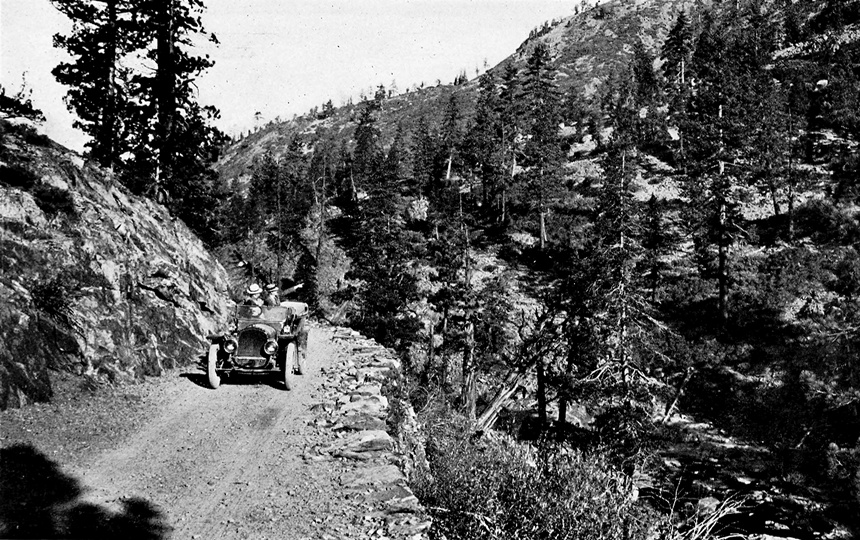

Paint-marked telephone poles let drivers know they were on the new Lincoln Highway, but little else immediately changed. The LHA’s 1916 Official Road Guide called the journey “something of a sporting proposition” and estimated it would take a “pleasure party” about 20-30 days to make the trip from coast to coast. Along the way, they might face rockslides going through mountain passes or get stuck in the mud and have to wait for a horsedrawn wagon to pull them out.

Spencer Simpson, manager of visitor services at the Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor in Pennsylvania, says that before starting their drive, travelers had to properly equip themselves with supplies like a shovel for digging out of mud, a mirror for signaling for help, and tools to make repairs. The Official Road Guide also encouraged them to take camp supplies like a 5-gallon milk can for water and Vaseline for gun maintenance and burns. Despite the risk, the Lincoln Highway revolutionized travel.

Simpson explains that, for people then, the highway could be likened to having your own private jet after flying commercial. They could suddenly travel whenever they wanted and could get to their destination in less time as the highway improved, which was ultimately Fisher’s goal. He didn’t just want a coast-to-coast highway, but an improved one that encouraged people to drive.

To showcase what interstate highways could be, the LHA created “seedling miles” by donating cement to communities and asking them to pave their section. Some went all out, adding features like electric lights and roadside art to their paved example, but even if they didn’t, the difference between paved and unpaved was obvious. Fisher hoped that once drivers experienced concrete roads, they’d fund similar construction in their communities, and soon, the entire highway would be concrete.

The LHA had a slogan for the plan: “Great oaks from little acorns grow; long roads of concrete from seedling miles will spring.”

The Main Street of America

Even without the concrete, drivers embraced the Lincoln Highway, and it quickly earned its nickname Main Street of America for two reasons. First, the highway went through many towns on their main road. But the Lincoln Highway also served as the nation’s literal Main Street, connecting towns and cities in the same way a community’s main road connected essentials like the store and doctor’s office.

While many took the Lincoln Highway to get from one coast to the other or to visit one of the newly formed national parks, they were just as likely to pack a picnic and go for a Sunday drive. Dwight D. Eisenhower didn’t fall into any of these categories. In 1919, the future president, then a lieutenant colonel, crossed the nation on the Lincoln Highway as part of a military convoy. Rein says the Army wanted to demonstrate how improved roads could help move men and equipment more efficiently.

“I’m sure that inspired Eisenhower to have an interstate system when he was president,” he continues.

Before Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act 1956, paving the way for our modern interstates, an association of state highway and transportation departments adopted a numbered highway system to replace named ones in 1926, but the numbered highways didn’t always correspond to existing named highways As a result, the Lincoln Highway became US 30 through the Midwest and US 40, US 50 and other numbered highways elsewhere.

So drivers could still follow the Lincoln Highway, its highway association created 3,000 concrete markers and asked local Boy Scout Troops to place them. However, because the original Lincoln Highway didn’t perfectly align with the new numbered highways, large sections needed to be rerouted.

Rein believes that replacing the Lincoln Highway with numbered highways and rerouting portions of it led to the the highway’s decline. Simpson blames larger, faster-moving highways such as the Pennsylvania Turnpike, opened in 1940, or Interstate 80, opened in 1956. Either way, by the end of the 1920s, the Lincoln Highway had begun seeing less traffic.

The Lincoln Highway’s Legacy

As the Lincoln Highway faded into the background of numbered highways, Route 66 rose to prominence and has remained there for the last 100 years. (The so-called Mother Road celebrates its centennial in 2026.) Simpson credits the early 1960s TV show Route 66 and the iconic Chuck Berry song, “(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66,” with its popularity. Rein agrees, adding that Route 66 is also a little easier to navigate today.

That doesn’t mean it isn’t worth the effort to experience the Lincoln Highway. Sarah Focke, a member of the LHA board of directors representing Nebraska, encourages people to get off the interstate and explore the Lincoln Highway.

“It’s a two-lane road that takes you through rural America,” she says. “You’re going through a small town every seven to ten miles, past cafes and post offices and historic buildings.”

She points to Lincoln Highway-era sights visitors can see while taking the route through Nebraska as examples: a seedling mile in Grand Island, a gift shop with a fort-like facade in North Platte, a giant covered wagon pulled by statuesque oxen in Kearney, and a brick-paved road that is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in Elkhorn.

Motorists today can also see the painted telephone poles and concrete markers drivers once followed across the nation on the Lincoln Highway. According to Rein, driving the highway is driving through time, and he encourages everyone to experience it.

“It’s a way to see the U.S.,” he explains. “It’s how auto travel developed. It goes through little towns, big cities like Philadelphia and Cheyenne. It drives past unique sights like the coffee pot in Pennsylvania. There’s all sorts of great stuff.”

Time is taking its toll, though. Many of the restaurants, motels, and attractions along the Lincoln Highway have fallen into disrepair and been torn down. Others, like the S.S. Grand View Point Ship Hotel in Bedford, Pennsylvania, have fallen victim to fire and other disasters.

“Why do I want to convince our visitors to see the Lincoln Highway?” he asks, referring to the people who visit the Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor’s museum in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. “Because tomorrow might be too late.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I still like traveling the old roads. Hwy 30 in central PA from Bedford to Jennerstown is fantastic scenery. Out west stopping at the Corn Palace or Wall drugs is a welcome break. 66 thru Texas and NM has been paved over but the Petrified Forest is a great side show as well as driving thru Gallup. I do wish that Fort Apache was still there on the AZ border.

I take long vacations in my motorhome and take the back roads every chance I get. A great senic view is old 290 east of Fort Stockton TX off of I-10 . Enjoy these while they haven’t installed a thousand traffic lights yet.

When I worked in Iselin NJ the business was on the Lincoln Highway

I have followed Route 66 on a motorcycle using various resources and following the few historical signs which exist state to state. Unfortunately not every state marks their portion of Route 66 very well and you may well drive to a dead end in sections.

My guess is the Lincoln Highway is much the same. I have picked up US 30 going east in far eastern WY and ridden to central Iowa and would like to again tackle riding the entire route. But unlike Route 66, it is quite difficult finding resources to follow along with a map to follow which road when.

Personally, I think its sad Route 66 and the Lincoln Highway are not recognized on maps and/or been decertified and replaced by the ugly interstates which cross our beautiful nation. I don’t want to take the fastest route. I like to be able to go at a slower pace, stop and look around every now and then finding something new to experience along the way. Sadlly, the younger generations care nothing to learn about or remember the history these highways hold.