“It is the times which are behind me”1

Today there’s nothing unusual about women wearing slacks or voting during elections. All that was forbidden in the 19th century when Dr. Mary Edwards Walker shocked others by refusing to wear corsets, dressing in long pants and demanding women’s right to vote.

The concepts of duty and doing the right thing led Walker to spend her life protesting society’s restrictions on women. Born on November 26, 1832, her parents’ progressive ideas on gender and racial equality inspired Mary to question social injustices and restrictive laws, as told in Sara Latta’s book, I Could Not Do Otherwise: The Remarkable Life of Dr. Mary Edwards Walker.

As a teenager working on the family farm, she refused to wear a corset. “No, sir; my waist has never been confined in one of those steel traps; it is just as natured intended it should be – free and unconfined,” Walker later told an interviewer. After teaching school in Minetto, New York, Walker paid her way through Syracuse Medical College despite the bias against woman doctors.

In contrast to conventional medical schools which recommended primitive “cures” like blood-letting and harmful medicines like mercury, the Syracuse Medical College endorsed a type of training known as “eclecticism,” which used herbals and hydrotherapy. (4) There, Walker met fellow free thinker and medical student Albert Miller and married him on November 16, 1855, but refused to use “obey” in her wedding vows and kept her maiden name.

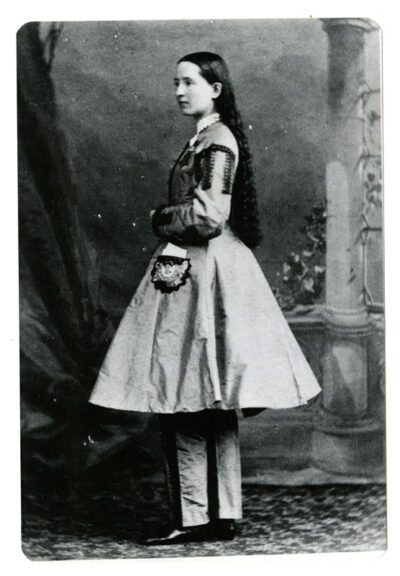

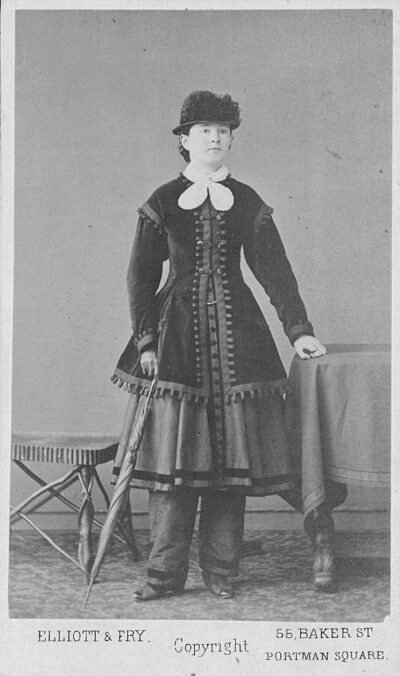

She and Miller started a medical practice in Rome, New York. To fully examine and treat patients meant she had to bend, stoop, or lean over them, but found her long skirts an impediment. To remedy that she shortened her skirts, wore long loose pants beneath them, and joined the feminist dress reform movement begun by Amelia Bloomer. To Walker free-fitting clothes were important to women’s health. She proclaimed, “The snug fit of the waist of the Dress or corsets prevents freedom of motion, of respiration, digestions…circulation of the blood,” according to Latta’s book.

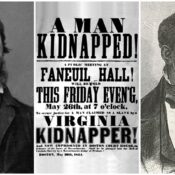

By 1859, after discovering her husband’s infidelity, she filed for divorce and relocated her practice elsewhere in Rome. That same year she began writing on abolition and dress reform for the feminist periodical, The Sibyl: A Review of the Tastes, Errors, and Fashions of Society.

Soon after the start of the Civil War, she tried to join the army as a surgeon. Denied because of her gender, Walker volunteered as a surgeon at a temporary hospital at the U.S. Patent Office. While there, she established the Women’s Relief Organization to aid those visiting wounded husbands and sons. By then she had abandoned bloomers for mid-length skirts worn over trousers and wore her curly hair long to affirm her identity as a woman.

Over the next year Walker cared for soldiers in Warrenton and Fredericksburg, Virginia and then Chattanooga, Tennessee to care for men wounded at the battle of Chickamauga. There, General Henry Thomas, having heard about her outstanding medical and organizational skills, appointed her to the 52nd Ohio Infantry, making her the first female surgeon to be appointed by the U.S. Army. Walker often crossed into enemy territory to heal wounded soldiers and sick citizens.

On April 10, 1864, just after helping a Confederate surgeon with the amputation of a soldier’s leg, she was arrested on charges of espionage and brought to the notorious Castle Thunder jail in Richmond, Viriginia. Upon her release from prison that August, Walker was weak, near starvation, and suffering from an eye infection. After the end of the war, Walker received a disability pension of $8.50 a month for partial muscular atrophy from her time in prison. On November 11, 1865, President Andrew Jackson awarded her the Congressional Medal of Honor, making her the first woman to receive the prestigious award.

Walker’s eyes were so badly damaged that she no longer practiced medicine and instead focused her energies on dress reform. While arrested in New York, New Orleans, and Kansas City for wearing men’s trousers and overcoats, she continued to press for sensible women’s clothing.

When heckled about her mannish attire, she retorted, “I don’t wear men’s clothes, I wear my own clothes.” In 1870, she worked with the Central Women’s Suffrage Bureau in Washington, D.C. and unsuccessfully supported mass registration for women to vote, according to the book, Mary Edwards Walker: The Only Female Medal of Honor Recipient. A year later she published Hit: Essays on Women’s Rights. Even more sensational was her 1878 book Unmasked or, The Science of Immorality: to Gentlemen, which discussed taboo subjects about human sexuality, including men’s abuse of a woman’s body. “Men treat women as though they had not a single right of existence and but for … sexual gratification, they would not be allowed to live,” she proclaimed in the book’s introduction.

A devoted supporter of the suffrage movement, Walker published “Crowning Constitutional Argument” in 1873 claiming the Constitution gave women the right to vote. In contrast, the feminist leaders of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) insisted upon the need for a separate Constitutional amendment. Their differing views caused them to part ways.

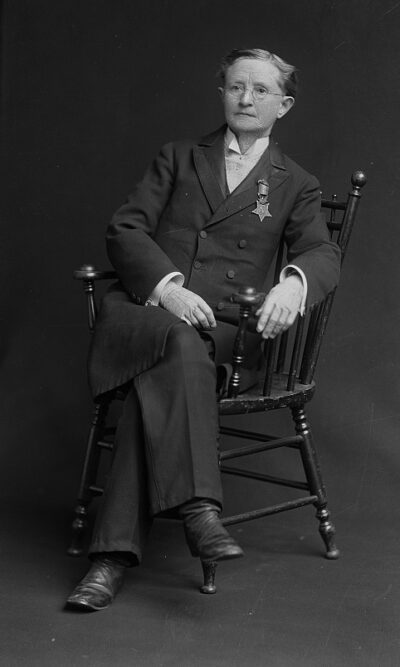

As she aged, Walker’s photos revealed a trim, bespectacled figure, dressed in a man’s shirt, a long waistcoat, trousers, and an occasional top hat, but always with the the bronze Medal of Honor pinned to her lapel. In 1917, after Congress revised standards for the medal for those only in actual combat, Walker’s medal was revoked along with 910 others. Appalled, she petitioned the army generals to reconsider. When they dismissed her plea and demanded she return the medal, she refused.

Instead, Walker continued to wear the medal every day of her life until her death on February 22, 1919, at age 87.

In 1977, Walker’s medal was posthumously reinstated during President Jimmy Carter’s administration through the Army’s Assistant Secretary of Manpower and Reserve Affairs by the Board for Corrections of Military Records.

Other Honors

- During World War II, a Liberty ship, the S.S. Mary Walker, was named for her

- A U.S. Postal Stamp was issued in her honor during the war

- Walker was inducted into the Women’s Hall of Fame in 2000

- Walker was honored with a 2024 American Women Quarter

- Latta, Sara. I Could Not Do Otherwise: The Remarkable Life of Mary Edwards Walker (Zest Boooks, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2022)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now