Thundersnow sounds like an awesome name for a rock band from northern Minnesota, or maybe a trans-Arctic snowmobile race, but as the term suggests, it’s a regular snowstorm with a bit of thunder and lightning thrown in as special effects.

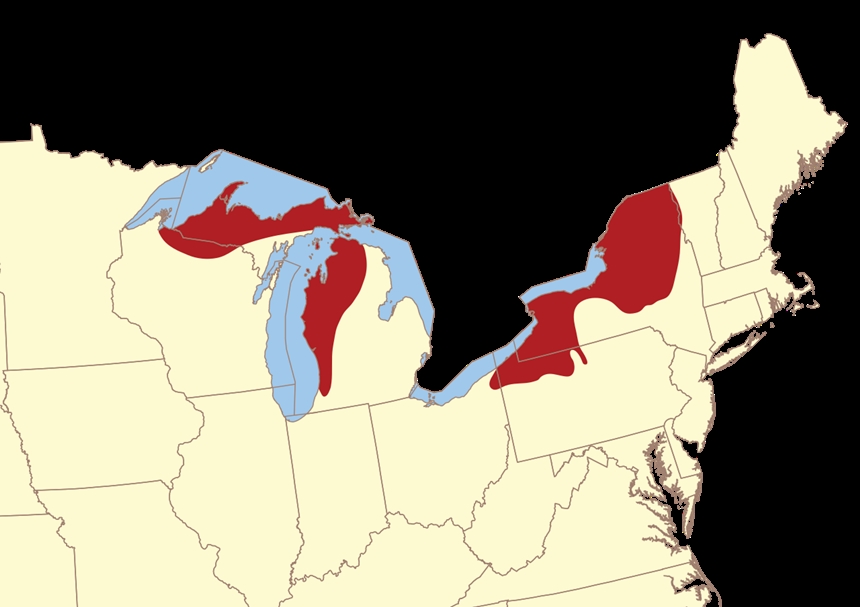

Worldwide, thundersnow events are unusual, but they are fairly common during lake-effect snow storms. This type of snow occurs when frigid air swoops down and passes over the open waters of any of the Great Lakes, the St. Lawrence River, or a marine inlet or bay, dumping huge amounts of snow when the cold air mass hits land. In northeastern North America, this tends to be just east or southeast of large water bodies. Such places are called snow-belt regions.

Although the Buffalo, New York area east of Lake Erie, as well as communities along the eastern end of Lake Ontario from Oswego, New York north to Watertown, NewYork are well-known snow belts, other regions can get hit by lake-effect storms, and thus thundersnow, too.

Depending on the wind, lake effect systems can reach 100 or more miles from a large body of water. The British Isles, northern Japan, and parts of Nova Scotia also get more frequent thundersnow than the rest of the world.

Thundersnow in Kansas (Uploaded to YouTube by CNN)

In the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) tradition, the storytelling season typically comes to an end after the first thunder of the year. I don’t know what kind of a wrench winter thunder might throw into the works, however. For those Haudenosaunee who love storytelling (all, I assume), one good thing is that lake-effect snow can fall at a rate of three inches or more per hour, making a very good acoustic blanket. The sound of thunder during snow storms is muffled, and only carries a short distance – two to three miles at most – unlike thunder during a rain storm, which may be audible for up to ten miles.

Sometimes, a thundersnow storm can produce round, light ice pellets that look much like Styrofoam beads used in packing. They squeak underfoot the way Styrofoam would, and even actually feel like packing beads, except colder. These pellets are known as graupel, a German word meaning “packing beads that are perfect for beer coolers.” Or something like that, I assume. The appearance of graupel is actually a warning sign that lightning strikes may soon occur.

Lightning in wintertime is potentially more dangerous than it is in summer. Because snow dampens the sound of thunder, people may not hear it and take appropriate cover until lightning strikes are very close by. The one saving grace is that not as many people are outside swimming, golfing, and picnicking in the winter. Usually, anyway. Even so, injuries and fatalities from winter lightning do occur from time to time. Perhaps because a sledder’s body is in close contact with the snow, anecdotal evidence suggests that lightning may injure sledders more than others who are outside during winter.

Although lake-effect regions see more than their fair share of thundersnow (and snow, deicing salt, snow, road closures, snow, school closures, snow, etc.), consider this: The World Meteorological Organization reports that Kampala, Uganda has on average 280 thunderstorms per year. This means that residents get a chance to get hit by lightning every 31 hours or so!

And in the winter of 1971-72, Mt. Rainier in Washington State set a world record by getting pummeled with 1,122 inches (93 ½) feet of snow. In light of these facts, I’d say snow-belt residents have nothing to complain about in terms of thundersnow. But then, they don’t tend to be a complaining lot, anyway.

Another type of mid-winter “thunder” happens when we go into the deep-freeze with little or no snow cover, and the ground quickly freezes. In these conditions, the ground can expand and suddenly shift a bit, especially around buildings and rock formations, creating a very localized mini-earthquake that is accompanied by a pretty unsettling boom. This is called a cryoseism, or frost-quake. I’ve only experienced one in my life, in northern New York State during the winter of 2005-2006, and it scared the heck out of me (on the plus side, I remained heck-free for many years afterward).

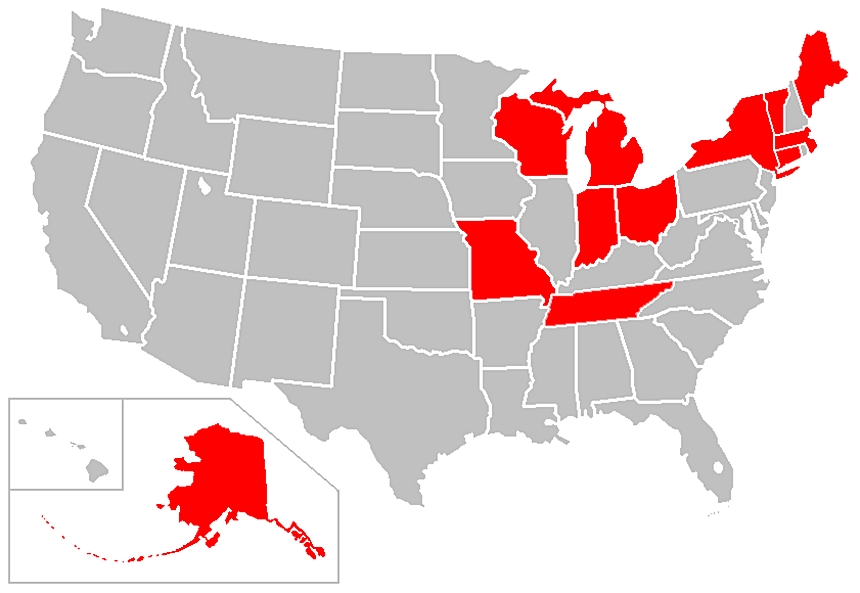

Cryoseisms require soil that is saturated, or nearly so, with moisture prior to freezing, as well as a steep drop in temperature that holds for a couple of snow-free days, which is why they are both unusual and nearly impossible to predict. That said, certain parts of the country seem to get more than their fair share of these ice-quakes. Alaska, Indiana, Ohio, Maine, Michigan, Missouri, New York, Tennessee, Vermont, and Wisconsin report the most cryoseisms. A few people, including one couple from Kansas, have managed to record the boom made by ice-quakes.

Cryoseisms (Uploaded to YouTube by KSNT News)

These days, when I hear something go pop on a cold winter’s night, I assume it’s my knees. But if you live in a part of the country that normally freezes up in winter, keep your ears open for the sound of thundersnow or an ice-quake.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Appreciate the article, links, and the 2 videos. I agree with Beatrice’s comment here about the earthquakes, living in northwest Los Angeles. As long as they’re 4.0 or under, it’s not much to worry about. The fires though are a very different story, statewide.

I experienced thundersnow once in Gallup, New Mexico. I believe it was in 91 or 92. It was definitely something that I had not heard of at that time and I stayed outside for at least 30 minutes waiting for it to happen again. Unfortunately that didn’t happen. I would love to see/hear it somewhere else at some point in my life.

I looked up the actual meaning of graupel & it means “The word graupel is Germanic in origin; it is the diminutive of Graupe, meaning “pearl barley.”

The map of lake effect snow is incomplete. Since childhood, I lived on the east side of Cleveland Ohio on and off for years. We had lake effect snow all the time. Same goes for the NW part of Indiana where the cold NW Canadian air can be warmed and humidified. By and large, once Lake Erie froze, the lake effect snow dropped off. Lake Erie is the shallowest of the Great Lakes.

I now live in Houston Texas where the heat index is 100 degrees for five months. The only time most people are outside is the get to their cars in parking lots.

Gosh I miss the lake effect snow.

That article about cryoseisms and thindersnow is the exact reason that I am glad my parents relocated me from Cincinnati, Ohio at the age of nine.

I’m much more comfortable living in Nothern California fearing only the occasional earthquake.

Love how your article is educational and yet you still add humor. What a dork, but so glad you were heck free for all of that time! I just want to be your friend! Lovely article. Thank you!

70 years ago, as an 8 year old, I watched a thundersnow in Western Massachusetts. The lightning cut through the night, illuminating the whirling blizzard— it was awesome, looking like we were living inside a roughly shaken snowstorm toy!