This year, 250 years after the start of the American Revolution, commemorations of the War of Independence will ramp up in earnest. Most historians trace the Revolutionary War’s origins to the April 1775 battles of Lexington and Concord, and so their anniversaries — along with other 1775 events such as the Battle of Bunker Hill and the invasion of Canada — will no doubt prompt a great deal of public remembrance and conversation.

Such historic anniversaries are an important way to not just commemorate the past but truly engage with what they can tell us about our community and our present conflicts. But that process requires us to go beyond well-known events and individuals, and to engage with the stories of our history for every American community. Commemorating two other 2025 anniversaries alongside the Revolutionary ones can help us do just that.

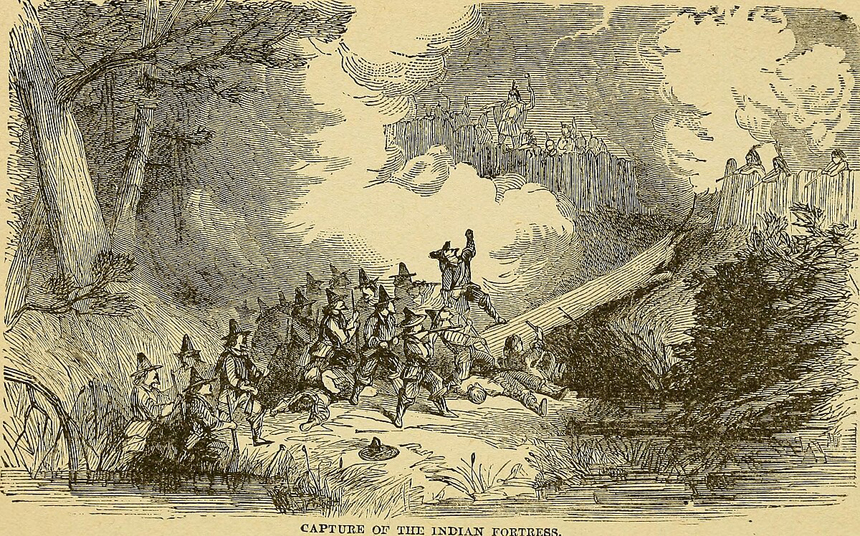

2025 marks the 350th anniversary of the first battles of King Philip’s War, the brutal late 17th century conflict between the English and Wampanoag that would rage across much of New England for nearly three years. Angered by more than 50 years of English violations of treaties and increasing incursions on their homelands, and led by a charismatic Pokanoket Wampanoag chief named Metacom (known to the English as Philip) who was determined to resist further displacement, the Wampanoag launched a series of raids on English settlements in the summer and early fall of 1675. In response, a number of English colonies formed the New England Confederation, which declared war on the Wampanoag on September 9. The war truly began with the December 19 Great Swamp Massacre, in which Confederation troops and Native allies burned a number of Narragansett Wampanoag towns, killing more than 600 and exiling the rest into a nearby swamp.

The anniversary of this brutal war allows us to reflect on the colonial violence out of which so much of early America was formed, and with what such wars meant for indigenous communities in particular. But it’s also important to see the Wampanoag as an American community, just as much as the English; in his powerful 1836 speech “Eulogy on King Philip,” the Native American minister and activist William Apess makes precisely that case for the Wampanoag chief. Apess begins by linking Philip to “the immortal Washington” as a revered ancestor, adding:

…even such is the immortal Philip honored, as held in memory by the degraded but yet grateful descendants who appreciate his character; so will every patriot, especially in this enlightened age, respect the rude yet all accomplished son of the forest, that died a martyr to his cause, though unsuccessful, yet as glorious as the American Revolution. Where, then, shall we place the hero of the wilderness?

Placing Metacom as an American revolutionary ancestor allows us to think differently about the crucial role of Native American communities in the unfolding American Revolutionary events of 1775. For example, breaking with the other members of their Confederacy, Oneida leaders voted to side with the colonists. The Oneida were one of the six nations that made up the Iroquois Confederacy, which had decided to remain neutral in the incipient conflict. Instead, in June 1775 they became the colonists’ first official allies and providing troops, supplies, and other support from 1775 until the war’s end.

Their Mohawk neighbors, on the other hand, had a longstanding trade relationship with the British, and decided that the best path to maintain both that relationship and their own tribal sovereignty was to ally with the British, defending New York from the Continental Army for much of the war.

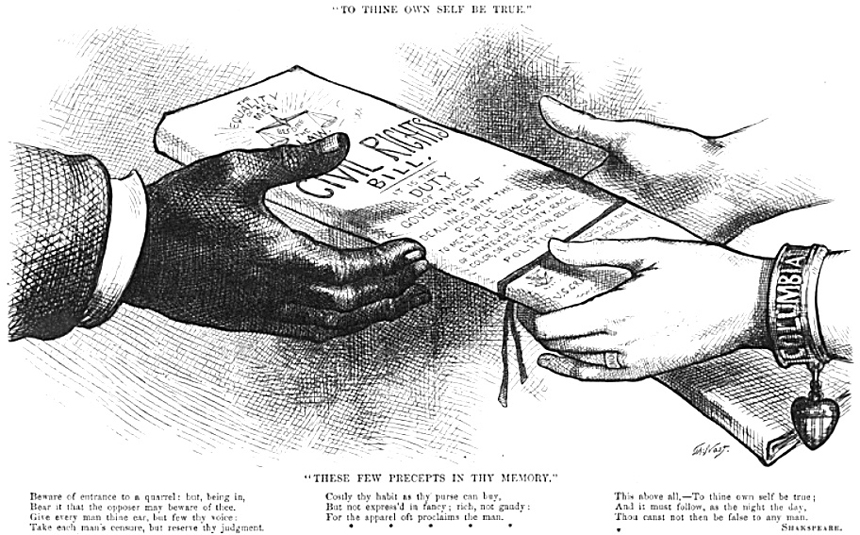

A century after 1775, America was in the midst of another complex revolution: the Reconstruction period in the aftermath of the Civil War. In his groundbreaking 2019 book, historian Eric Foner calls that period The Second Founding, noting how legal and political advances remade the Constitution, extending its rights and protections to all Americans. 1875 marks the 150th anniversary of a groundbreaking federal law that further extended and cemented Constitutional rights for African Americans and all American communities. That law was the Civil Rights Act of 1875, drafted by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, passed through Congress in February, and signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1.

Fully titled “An Act to Protect All Citizens in Their Civil and Legal Rights,” the 1875 law was the nation’s only federal civil rights law until the Great Society laws of the 1960s (also celebrating an important anniversary this year). While the law specifically focused on equal treatment in public accommodations and transportation, along with other rights like jury service, it also reflected a significant overarching idea: that the federal government could and should guarantee equality under the law for all Americans, not only through the Constitution but also through ongoing laws and policies to protect those Constitutional rights.

Illustrating that idea’s importance was a January 1874 speech delivered by South Carolina Congressman Robert Brown Elliott, one of 15 African Americans elected to Congress during Reconstruction. Elliott makes an impassioned case for a federal civil rights law, arguing that “even in the darkness of slavery” African Americans had “kept their allegiance to freedom and Union,” and that the nation owed them these protections and guarantees.

Commemorating the Civil Rights Act of 1875 can help us remember the complex role of Black Americans in the events of 1775. That includes the ways in which the nation’s founders too often excluded enslaved African Americans from their vision of America, exclusions that prompted many enslaved people to side with the British due to promises of emancipation. But it also includes the more than 5,000 African Americans who served in the Continental Army during the Revolution, such as the Black soldiers who took part in the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775. They too should be included in our 2025 commemorations if we’re going to truly reflect on the history of all Americans.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now