In the 2003 holiday film, Elf, Will Ferrell, as the titular elf, Buddy, finds himself working in a mailroom, proclaiming the pneumatic tube system to be “very sucky.”

Away from the movies, pneumatic tubes represent the bygone analog technologies of yesteryear, and like other devices from that era — think typewriters, fountain pens, and rotary phones — people can be downright sentimental about them. Growing up, I loved the sucking and slaps they made at the drive-through at the bank when my mom would deposit a check. More recently, at our local kids’ museum, I’ve probably had more fun with the small demonstration tube system than most of the actual kids.

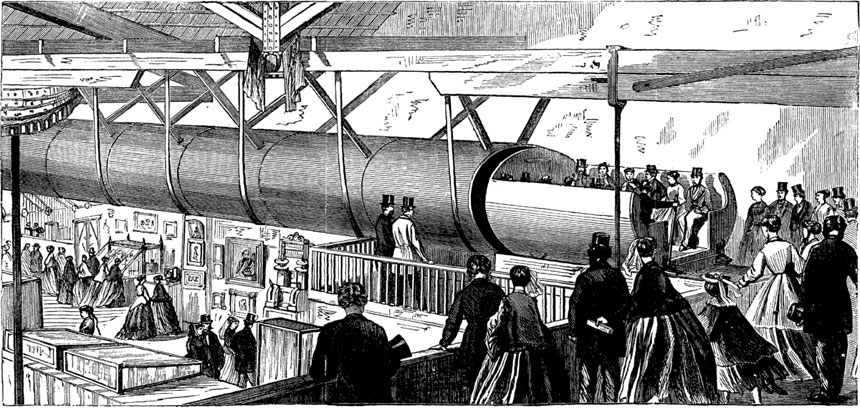

Pneumatic tubes were used to move mail in New York City, London, Germany, and Washington, D.C., and even transport food, cats, and yes, people. Tubes were the future, before they became part of the past. The scale of these systems covered dozens of blocks in sprawling cities. There was even a demonstration line in New York that pneumatically pushed people down about the length of a football field. While the human-carrying version didn’t last beyond the 1870s, pneumatic tubes that spanned cities were a reality by the early 20th century.

But pneumatic tubes haven’t gone away entirely, and are still used in places such as hospitals, where they quickly move supplies and samples from faraway parts of vast buildings to various departments. Sweden uses them to whisk away trash and recycling. And building planners are finding new ways to incorporate them in their plans.

Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago uses pneumatic tubes to deliver IV bags, blood, and medications through four miles of tubes connecting seven buildings (Uploaded to YouTube by CBS Chicago)

But there’s more to the story: Their fun, infrastructural history (and potential) is rooted not just in banks and mailrooms, but also newsrooms.

Pneumatic Tubes and Newsrooms

Pneumatic tubes were once part of the hidden infrastructure of the modern newspaper office, helping to tie these complex production spaces together. For most of the 20th century, newsrooms were essentially news factories, production facilities that pushed out a daily, industrialized product, more akin to milk than cars, perhaps, due to its perishable nature. Efficiency was critical.

While some ways of moving copy around newspaper buildings just involved gravity — i.e. dropping paper down chutes or pipes — pneumatic tubes used preset routes and metal pipes with compressed air or a partial vacuum to push (or suck) paper enclosed in a cylinder through newspaper buildings, both within newsrooms, for editing (from reporters to copy editors, for example), and then to printing facilities for final layout and production. They allowed reporters and editors to remain in place and to continue their jobs instead of having to spend time walking a piece of copy from one room to another, or from one building to another.

In Chicago, for example, the City Press news network, a cooperative news agency that connected the Associated Press, the Chicago American, the Chicago Daily News, the Chicago Sun-Times, and the Chicago Tribune, used a pneumatic tube system that was nearly 15 miles long and carried nearly 269,000 messages a year, ranging from photos to press releases to story drafts, often to copydesks for further processing. These tubes moved copy through crowded, busy newsroom spaces bustling with human labor, and led by editors obsessed with getting the news out at quickly as possible.

Like a body’s circulatory system, tubes carried the daily data of the newspaper’s newsroom throughout the building. In addition to newspaper copy, occasional mice, felt hats, and billiard balls arrived with a whoosh and a bang, according to Eddie Kitch, who wrote about tube antics in a January 1954 Quill article. The system used minimal electricity and space (at least compared to many of the other machines used to manufacture the news, especially later in the 20th century).

From the 1910s through the 1950s, their use was gradually reduced as newsrooms and newspaper buildings were renovated. By the 1960s and 1970s , many of these systems, in Chicago and elsewhere, were phased out as fax machines, voicemail, and early intranet messages (and later email) supplanted them.

Showing Off the Power of “New” Technology

But for a few glorious years, pneumatic tubes were the pride of many a newspaper. They were highlighted in newsroom profiles in journalism trade publications such as Quill and Editor & Publisher as state-of-the-art tools that showed that newspapers were at the forefront of innovation. Publishers were proud to discuss the latest gadgets installed in their new or newly renovated newspaper buildings, and rank-and-file news workers were equally eager to share how they made their working lives easier. A $4 million ($72 million today) renovation of the Pittsburgh Press in 1927 bragged about the inclusion of pneumatic tubes as part of a modern, “straight-line process.”

And a 1927 profile in Editor & Publisher highlighted pneumatic tubes in a more modest renovation of the newsroom of the Akron Beacon-Journal in Ohio (valued at $1 million, or $18 million today). The article emphasized the value of “communication with editorial and advertising departments” in the center of the newsroom, likely as part of an attempt to streamline the placement of the vital ad copy that provided the majority of the paper’s profits. The movement of ads, along with stories, was one of the main uses of tube systems.

As late as 1957, pneumatic tubes were still seen as innovative, especially for large, increasingly multisite newspapers such as the Chicago Sun-Times. A newspaper might have a primary newsroom, but also a number of other facilities on site, including a printing plant, a business office, and storage (and, in some cases, a motor pool for its delivery trucks).

Showing Off Newsroom Efficiency

In many cases, pneumatic-tube systems were heralded not just as a technology showcase, but as a means toward the ideal of productivity. Stairs were enemies of efficiency; tubes were the solution

Pneumatic tubes that could shave off as few as 45 seconds from the copy-transmission process were highlighted as important developments, according to a December 1930 Editor & Publisher article. At especially massive newspapers, such as the Los Angeles Times, tubes would connect the editor-in-chief and managing editor to the telegraph, news, and city editors, the copy desk, and then on down the chain of command, in newsrooms that had hundreds of desks and offices. Marketing and editorial coverage of such technologies emphasized their physical power – driven by “100 pounds” of air pressure – and their capacity to connect different facets of an increasingly sprawling news ecosystem, according to an August 1935 Editor & Publisher story.

“The time saving is considerable,” editor Eugene Pulliam observed: “The wear and tear on nerves even more so.” Back in Chicago at the City Press network, a 1954 Quill story noted that “The carriers are placed in the tubes and are sucked to their destinations where they land with a bang that long acclimated rewrite men, editors, and copyreaders no longer even hear – loud as it is.” The aural environment of the newsroom would, in time, grow quieter, but these bangs, thumps, and bumps literally conveyed the movement of news around the buildings and centers of news production for more than half a century. Perhaps only teletypes and typewriters were more iconic in terms of their workaday noise and their contribution to the soundscapes of the newsroom.

The Legacy of Pneumatic Tubes at Newspapers

For the majority of the 20th century pneumatic tubes did the job, admirably, fading only with the advent of computerization and then the internet itself.

Pneumatic tubes were an antecedent technology to our still-hybrid analog-digital information society. These tubes handled the copious and unrelenting data traffic generated by the newsrooms of the early- to mid-twentieth century. These spaces were the harbingers of the kinds of information-society companies we take for granted today.

Sometimes “old” technologies work well, complementing rather than being totally supplanted by the new. UK hospitals and Swedish trash companies recognized that sometimes older technologies can be repurposed for our modern needs.

Pneumatic tubes, in their way, remain with us, and will for some time to come.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

These were well in use at NASA’s Mission Control up until the 1990s. We used to send all sorts of things through the P-tubes (as we called them), from flight notes to candy. There were two separate systems installed with the Shuttle program; the legacy system that dated back to the Gemini days and ran all through the building, and the classified P-tube for secret DoD Shuttle missions that only ran around the third floor of the building. The classified P-tube used clear plastic containers like the photo in the story; the legacy system used metal cylinders about a foot long.

Thanks folks! I appreciate these comments — glad you liked it.

I was in the U.S. Navy from 1976 to 1980, stationed at a shore station, not on a ship or sub, fortunately.

We used those tubes to move messages, sometimes

Secret or Top Secret, from the Radio Room to the office floor. And at least once in those 3 1/2 years, somebody used it to transport something Unclassified, like a bag of M&M’s !

I don’t know what the banks around the small rural communities would do with out these, especially those in use with their drive-by windows. I have heard however there is a weight limit of what they can transfer, especially when it comes to coinage. I’ve heard from local bankers that too many coins being transferred by these may either not be able to be pulled up, become stuck along the transfer, or come in so fast and hard that it can result in damage on the receiving end or injury to the teller receiving. Some banks place a weight limit notice on the canal itself where customers are advised to come inside the bank to complete their business.

This is extremely fascinating to me. I never knew they were called pneumatic tubes though, having worked in an office in the 80’s that did use them for inter-office use. They did make this cool ‘jet-age’ vacuum sound as the paperwork disappeared. The fact the tubes were clear made it all the more fun to watch.

The elevated New York subway system illustration of 1867 had to have been very futuristic for those people. Technology was accelerating faster and faster in the late 19th century, pushing the industrial revolution to heretofore ridiculous levels of speed. And the pneumatic tube technology would have gone hand in hand with the vacuum cleaner as we would know it.

And, at that time, the new version of the Post (as a magazine) to showcase all of the wonderful new inventions just coming into being you wanted and needed advertised on those oversized pages, to make YOUR life better and easier! I definitely think the idea can be repurposed for modern times and needs in both Europe AND the U.S.