Those who are familiar with the term Yule log might think of the scrumptious log-shaped cake served at Christmas time. Also known as Bûche de Noël, owing to its French origin, this kind of log is a rolled sponge cake filled with buttercream and covered in chocolate icing textured to look like tree bark.

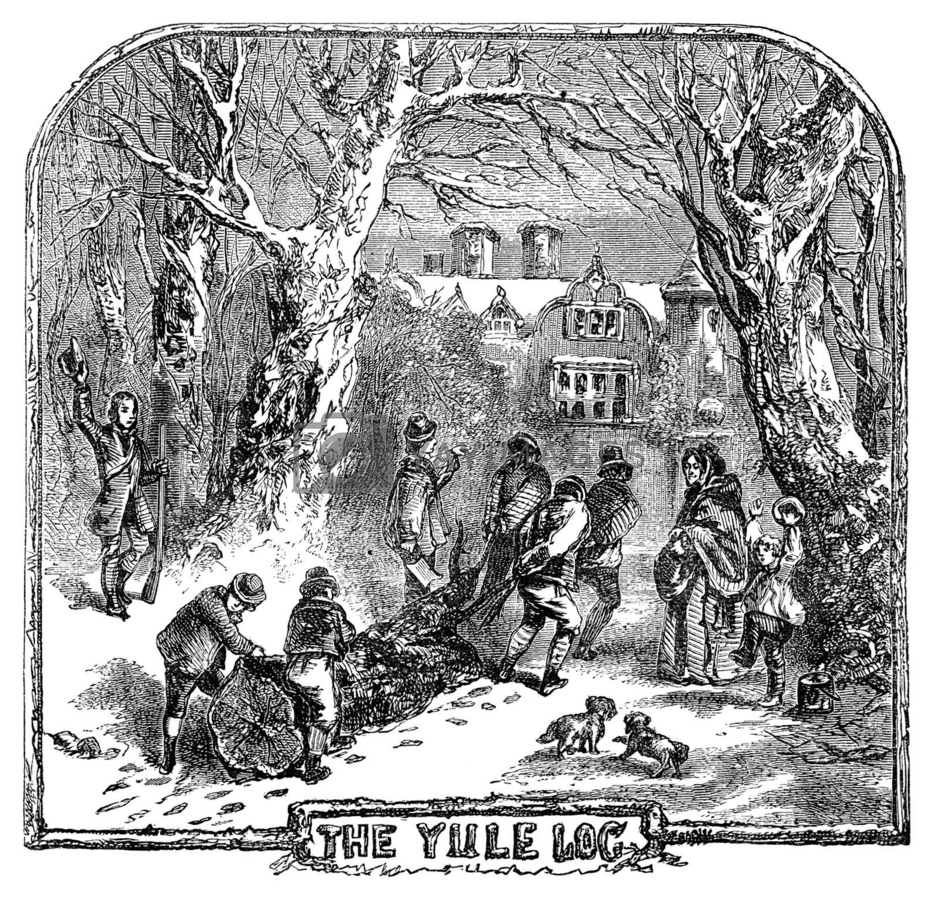

In the distant past, however, folks happily burned Yule logs until ashes and charcoal were all that remained, because the Yule log was an actual log. The custom of burning a real Yule log has largely fizzled out in most parts of the world. But for centuries, ancient Nordic, Germanic, Celtic, and other peoples welcomed back the lengthening days on the winter solstice by partying around a fire where a Yule log burned.

Yule logs of centuries ago in northern Europe were so big that sometimes only one end would fit into the fireplace, with the rest of the log running the length of the house. These tree trunks were meant to burn all day, and in certain cultures for twelve straight days. People typically felled an oak tree, as its dense, hard wood doesn’t burn very fast. And you wanted the Yule log to last a long time, because you had to save a piece for next year. Or else.

If you didn’t save a piece of the log for the following year, you might have twelve months of bad luck — your house might get hit by lightning and catch fire, or some other misfortune would befall you. A blackened hunk of the log was placed under the bed or squirreled away in the rafters as a kind of fire insurance. (This could certainly backfire if the charred piece of Yule log was not fully extinguished before it was stashed.) A year later, it would be retrieved and used to light the new Yule log.

While a birch log is picturesque, it doesn’t stack up against many other hardwoods in terms of the heat it will give off and how long it will burn. In the U.S. and Canada, the heat value of wood and other fuels is measured in British thermal units or BTUs. One BTU is the energy required to heat one pound of water by one degree Fahrenheit. Ironically, the British tossed the BTU in the dust-bin 25 years ago and switched to Joules, the unit the rest of the world uses.

Firewood BTU-value charts seldom agree exactly. This is to be expected, as the heat value of a given species varies based on the conditions in which it grew. For example, a slow-growing sugar maple is denser, and has more heat value, than one on better soil that grows fast. Wind-exposed trees produce more energy-rich wood than the same trees in sheltered sites.

Fuel wood is measured in cords: A full cord is 128 cubic feet — four feet high by eight feet long and four feet deep; and a face cord is sixteen inches wide by four feet high and eight feet long. There are three face cords in a full cord.

In general, hardwoods make better fuel. But this is a misnomer, as some have softer wood than softwoods or conifers. Quaking aspen, technically a hardwood, has around 12 million BTUs (mBTUs) per full dry cord, lower than white pine, a softwood rated at 16 mBTUs. Among species with the most heat value are live-oak (36.6), Osage orange (32.9), and sugar maple (27.5). Premium fuelwood species differ according to geography. Osage orange does not grow in the Northeast, and live-oak is not found up north. In many western states such as Idaho, as well as up in Alaska, softwood species are commonly burned because often, little else is available for firewood.

Aside from BTU value, moisture is a key factor when heating with wood. If wood is green (recently cut), a lot of its heat value goes into boiling off the water it contains. Green wood also leads to heavy creosote buildup in chimneys, creating a fire hazard. Those Yule logs of yore were green, which helped them last longer, and heat wasn’t the point anyway.

In the Balkans and parts of southern Europe, and among a few modern-day pagans here at home, a genuine Yule log tradition still burns on.

Though you can find many online sites with perpetually burning Yule logs this holiday season, the original was a TV program started in 1967 that has been going ever since. Considering its 57-year burn time, we could probably solve the world’s energy problems if we could plant more of whatever kind of tree that wood came from. Of course, 1967 was during the Cold War when a lot of covert studies were done, so it might be from a classified project.

WPIX The original Yule log (Uploaded to YouTube by Burrns Luciano)

If you’re going to bake your own Bûche de Noël this year, try not to burn it. But if you plan to light an old-fashioned Yule log in an open hearth, you likely will pick a high-BTU hardwood species for a long burn. Given the information above, I’m sure Yule choose wisely.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you Paul, for this fascinating, yuletide story here. It’s astonishing to say the least, and I’ll never look at the fireplace the same way ever again. Yet another example of the ’60s showing what a long reach they have into the present and beyond.