On the Great Wheel of Popular Culture, something that had the spotlight in the past often comes back around again in a big way. We’re currently in a season of massive success for Wicked, a musical film based on a Broadway musical that was based on a novel which was inspired by a musical film that was based on the second version of a musical stage play that came from a novel. No matter how you slice it, Oz owes its fictional existence to L. Frank Baum. Here are five facts about Baum, his wonderful wizard, and everything that came after.

1. The Origins of Oz

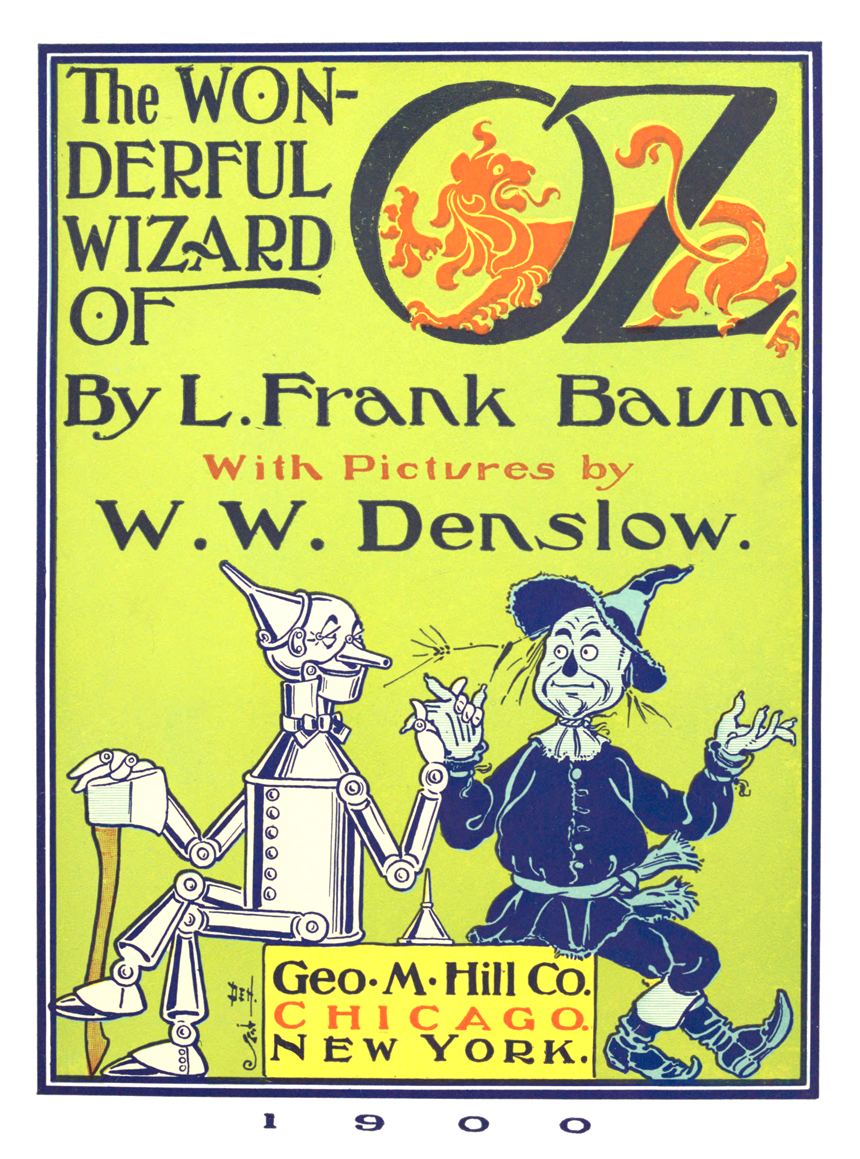

Lyman Frank Baum was born in New York In 1856. He grew up on the family estate, as his father was successful in multiple ventures like real estate and oil. Baum himself had health struggles in his youth. When Baum showed an interest in writing, his dad bought him his own printing press. His younger brother, Clay, helped him produce a small magazine called The Rose Lawn Home Journal, which was named after the family estate. When he was 17, he started a stamp collecting magazine. By 1880, after experience with rearing chickens, he founded The Poultry Record as a monthly trade journal. He also got involved in theater, working on productions and writing plays; he even composed songs for The Maid of Arran. After unsuccessfully running a store and then a newspaper in Dakota Territory, he, his wife, and four sons relocated to Chicago where he worked in publishing and sales. His 1897 children’s book, Mother Goose in Prose, did well enough that he could write full-time. He followed it up with the poetry book Father Goose, His Book, and it outsold all other children’s books in 1899. That book was illustrated by W.W. Denslow, and Baum invited Denslow to provide art for his next book, 1900’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Baum’s primary creative drive for the book was the notion of a modern fairy tale. The Scarecrow was inspired by Baum’s own childhood nightmares of being chased by a straw man, and the Tin Woodsman was based on a window display figure that Baum had actually built himself. Dorothy drew her name from his niece, who had died at the age of five months. He dedicated the book to his wife, Maud, who had been devastated by the infant’s passing. Baum also drew inspiration from his mother-in-law, Matilda Joslyn Gage, a towering figure in American social movements that included suffrage, abolitionism, and Native American rights; her own research on witch hunting and the phenomenon’s deleterious effect on women in society inspired Baum’s notion to create two sets of witches in opposition.

2. The Play’s the Thing

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz sold out its initial printing of 10,000 copies, a month after its September 1900 release, and another 15,000 copies were gone a month after that. The publisher, George M. Hill Company, had originally backed the book when the Chicago Grand Opera House agreed to create a play that would act as a promotional venture. Baum contributed to the scriptwhich originally opened as a play and was quickly converted into a full-on musical in 1902. The musical, which shortened the title to The Wizard of Oz, was a hit and drove sales of the book. The success of the stage show ignited a creative fire for Oz in Baum, and he would write 13 more books before he passed in 1919 (the final two books, The Magic of Oz and Glinda of Oz, were published in 1919 and 1920, respectively, after his death). By 1938, over a million copies of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz were in print.

3. The Lost Oz Series

The 1910 Wizard of Oz (Uploaded to YouTube by SilenceIntoSound)

The stage version of The Wizard of Oz was actually adapted into a little-remembered short film, which was released in 1910. Produced by Selig Polyscope Company, the 13-minute movie takes incredible liberties with the story (like the earlier stage musical, Toto is swapped out for . . . a cow). Three more films were made that year: Dorothy and the Scarecrow in Oz, The Land of Oz, and John Dough and the Cherub. However, no surviving prints have been located. The 1910 Wizard is available in film archive compilations and the three-disc set of the 1939 film.

4. The Movie We All Remember

Dorothy (Judy Garland) sings “Over the Rainbow” in The Wizard of Oz (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

The beloved 1939 film version of The Wizard of Oz wasn’t immediately and universally acclaimed as an instant classic. Filming was riddled with all sorts of problems, including the illness and withdrawal of original Tin Man, Buddy Ebsen, a rotating series of directors, and on-set injuries to “Wicked Witch of the West” Margaret Hamilton (she sustained burns during the witch’s appearance in a column of smoke).

The film made a small profit when it was released, and received five Academy Award nominations. It won for Best Song (“Over the Rainbow”) and Best Score while also locking up Best Performances by a Juvenile for Judy Garland, who received the now-retired award for Oz and Babes in Arms. It wasn’t until a decade later, upon its 1949 re-release in theatres, that the film generated what was considered a successful box office return. It also received much more notice, causing people to reconsider the greatness of the film.

For Baby Boomers and Generation Xers, the real arrival of Oz came when the film began appearing on broadcast television. Debuting in 1956, it pulled in more than 45 million viewers. Three years later, it began running as an annual event; with only one interruption (the regular holiday showing in 1963 was skipped as the United States mourned the loss of President John F. Kennedy), Oz continued its once-a-year showings until 1991. Today, the film is available on a number of streaming services.

5. Getting Wicked

“Ease on Down the Road” from The Wiz (Uploaded to YouTube by Universal Pictures)

The Oz series has been the subject of numerous adaptations and expansions. A popular anime called The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Ozu no Mahōtsukai) ran in Japan in 1986 and 1987; the 52-episode series adapted four of Baum’s books. Of course, there’s The Wiz, the soul-inspired 1975 winner of seven Tonys, including Best Musical, that became a 1978 film starring Diana Ross and Michael Jackson. Eric Shanower has written several original Oz graphic novels and adapted the first six Baum books for Marvel Comics with artist Scottie Young, the most recent in 2020. Other alternative takes include the SyFy channel mini-series Tin Man from 2007, Disney’s wonderfully insane Return to Oz from 1985, and the use of related characters in ABC’s 2011-2018 series, Once Upon a Time.

Wicked trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Universal Pictures)

However, anyone paying attention knows that this is the season of Wicked, the big-budget two-part movie adaptation of the stage musical, which is based on the novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West by Gregory Maguire. The novel is a revisionist take on the Witch’s life, casting her as the put-upon protagonist. The Stephen Schwartz musical debuted in 2003; it was nominated for ten Tony Awards, winning three (Best Costume Design, Best Scenic Design, and Best Actress for Idina Menzel as the “Wicked Witch” Elphaba). Since its November 22 release, the film has grossed an amazing $366 million worldwide; by the end of Thanksgiving weekend, it was already the largest grossing stage musical-to-screen adaption in the United States, eclipsing Grease. The second film is set to open in November of 2025.

CHRISTMAS BONUS: L. Frank Baum contributed to the myths of Saint Nick with his 1902 book, The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus. It posits a baby Santa is found by the immortal Ak, who would entrust his care to a lioness and wood nymph. Santa eventually invents toys, which angers the demons that make children misbehave; this leads to a war between the immortals and the demons and their monster allies. The Council of Immortals later debate on whether they should add Santa to their ranks. Baum wrote a short story sequel called “A Kidnapped Santa Claus” that involves more demon chicanery. Rankin/Bass adapted it as one of their Animagic holiday specials in 1985.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

As a big “The Wizard of Oz” (1939 film) fan, I really love this feature, and appreciate the research you put into it. There’s a lot more to L. Frank Baum’s ‘Oz family tree’ than most of us realize, by far. It spans the entire 20th century, into the 21st.

I appreciate the 1910 video you included here. Though still an early version of the future film, it still had enough of the recognizable traits in it that would need to ‘bide its time’ until the right people at the right time would create a film with such state-of-the-art color, sound, and special effects, that films of the present cannot touch 85 years later. Indeed, all of these elements are long gone from films, not to mention the zeitgeist of that time, never to return again.

‘Wicked’ is doing extremely well. and that’s fine. I see it as another offshoot to the legendary film, just like ‘The Wiz’ of 46 years ago. I first became aware of it in 2007 when it was on stage at the Pantages from the TV ads. Didn’t care for the music or the concept, but have to admit the concept is clever; there’s a difference. By clarifying that, I’m not a hypocrite.