As December comes, the dark nights are suddenly becoming a little bit brighter as many decorate their houses for the season, and town centers across America are lighting giant trees covered in dazzling displays. Nothing marks the joy of the holiday season more than a celebration of light and color.

What now seems to us so essential to the holiday spirit began as a commercial ploy in the late nineteenth century when another wonder came into the world: electricity. The American invention of the light bulb did not only forever change the lifestyle of millions of people, but also the nature and meaning of Christmas.

Light displays and Christmas trees are a relatively new addition to the holiday tradition. In the famous 1823 poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” Santa Claus, sleighs, snow, and stockings were all part of the scene, but what was conspicuously missing was a tree. The custom of Christmas trees would arrive to the United States a little later, with the influx of German immigrants who would bring with them the tradition of the Winter Tree — a cut evergreen to be placed inside the home.

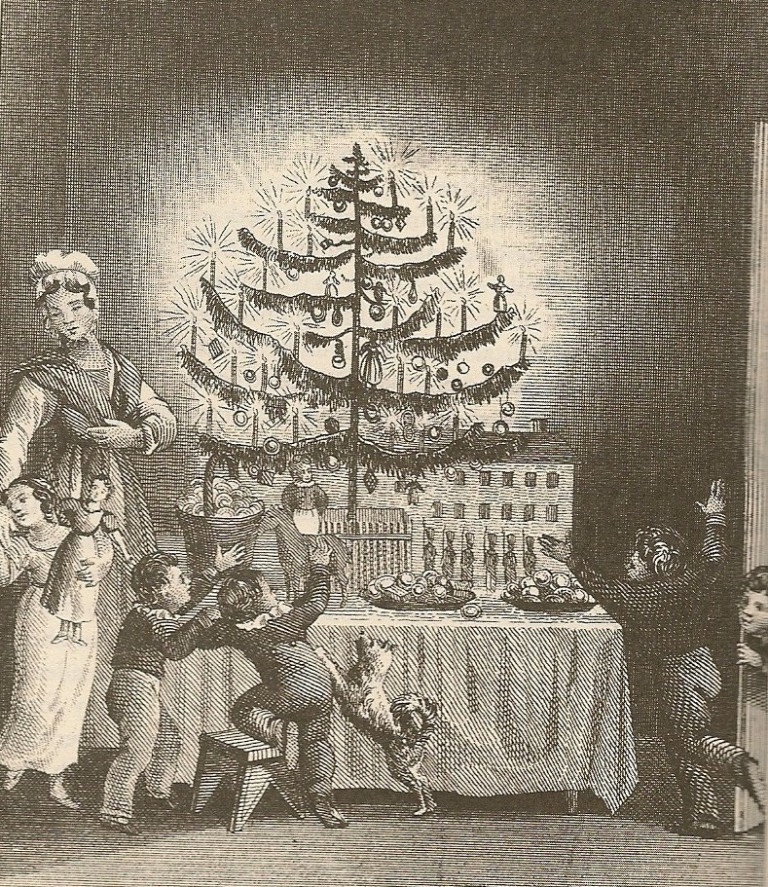

For most of the nineteenth century, the main markers of the holiday were candles and nativity scenes, emphasizing its religious nature. Christmas was not only a Christian celebration but also a familial one, often done in the privacy of homes and churches.

Decorated trees would not take hold in American culture until after the Civil War, and even then, the most common decorations were candles, precariously balanced on the branches and often lit for a short amount of time, and never overnight, to avoid a fire.

The advent of electricity changed all that. In 1880, Thomas Edison debuted the first electric Christmas light display in Menlo Park, New Jersey, showing investors the benefits of his invention. The New York Times commented how the “bleak and uninviting place” was “brilliantly lighted by a double row of electric lamps, which cast a soft and mellow light on all sides.” While the display was not necessarily themed around Christmas, its date (December 20), and the spirit it aroused connected it to the holiday.

Two years later, in 1882, Edison took this marketing strategy to a new level. On December 4, the first rotating Christmas tree covered with tiny colorful lights was displayed at the Upper East Side home of Edward H. Johnson, Edison’s partner and the vice president of Edison Electric Company. Johnson invited the press to see this new modern marvel, using the holiday spirit as a promotion for Edison’s products.

The new invention became a symbol of affluence and luxury, as only the few wealthy homes could afford to have electric-powered lighted trees. More than creating a new holiday tradition, the light-decorated Christmas tree was another way for the Gilded Age elite to harness technology to show their superiority.

However, by 1903, General Electric would sell strings of small colorful lights, making tree lighting available not only to the wealthy but also to the middle class. A string of 24 bulbs would have cost around $12 (about $430 today), and as electricity in homes became more prevalent, more and more could take part in this newly invented tradition. Those with fewer resources could also rent festive lights for the season to participate in the holiday spirit.

While properly decorating a tree still required large investment, the custom fit well into the new association of the holiday with commercialization and spending. Like the popularization of the figure of Santa Claus — who became the secularized version of St. Nicholas — the modern and luxurious association of the electric tree lights helped to secularize the more traditionally religious candles.

Christmas lights not only helped solidify the commercial nature of the holiday, but also facilitated its transformation into a community endeavor. In 1894, President Grover Cleveland would hold the first Christmas tree lighting in the White House, making it the first time when lighting a tree was not connected with commercial advertising.

It would take until 1912 for the first outdoor civic tree lighting ceremony to occur. That year, on Madison Square, a 70-foot-tree covered in 2,300 bulbs was lit in a communal ceremony open and free for all to see. According to the New York Tribune, almost 25,000 people showed up to witness the event. Rich and poor, immigrants and native-born, Jews and Christians — all came together to take part in the celebration.

By the following year, the Salvation Army would take charge of the event, distributing hot sausages and coffee to the crowd. The yearly ceremony would continue until the 1930s, where the tradition would move uptown to the newly erected Rockefeller Center.

The elevation of this non-religious mode of celebration together with the growing custom of community tree lighting made the idea of lights an easy tradition to relate to even for those who did not celebrate Christmas. Non-Germanic ethnic communities as well as Jews and other religions adopted the colorful light displays as a way to celebrate unity, generosity, and even patriotism. Lights belonged to everyone, regardless their creed, race, or socioeconomic status.

With Christmas and Hannukah overlapping this year, it’s a good time to remember this tradition. Whether it is a Christmas tree, a Nordic evergreen, or a Hannukah bush, thanks to Thomas Edison, we can all celebrate the magic of light.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now