This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

This past Sunday evening, five Republican state legislators in West Virginia sent a striking resolution on the 2024 presidential election to the West Virginia House Judiciary Committee. House Concurrent Resolution 203 would not recognize the election of a Democratic candidate for the presidency if the Republican candidates for president or vice president were “assassinated, seriously injured during an assassination attempt, incarcerated, de facto eliminated or barred from the ballot in any states, or is the subject of legal actions that preclude their effective campaigning.” The Resolution would also give the state attorney general and secretary of state the power to refuse to certify the state’s electoral results if they “determined” there to have been “election fraud or interference” anywhere in the U.S.

This action is just the latest of many through which West Virginia, while one of the smallest states in the U.S. in terms of both population and area, has played a significant role in American history, both reflecting and amplifying our defining debates and important issues.

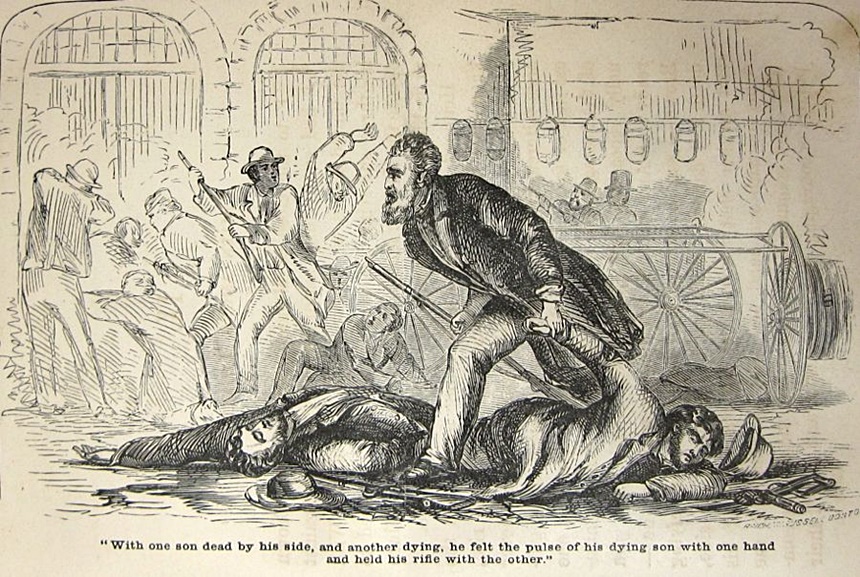

That role began with two crucial moments at the outset of the American Civil War. Even before West Virginia existed as a state, the region saw one of the most inciting actions in the nation’s move toward civil war: abolitionist activist John Brown’s raid on the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry. From October 16-18, 1859, Brown and his party of 22 supporters captured and held the federal arsenal, hoping to arm enslaved people in the area and create a slave revolt across the southern states. While the arsenal was eventually retaken, both the raid and the subsequent trial and execution of Brown galvanized both anti- and pro-slavery forces, contributed directly to Abraham Lincoln’s election as president in 1860, and has thus been defined by historians as an early action in the incipient Civil War.

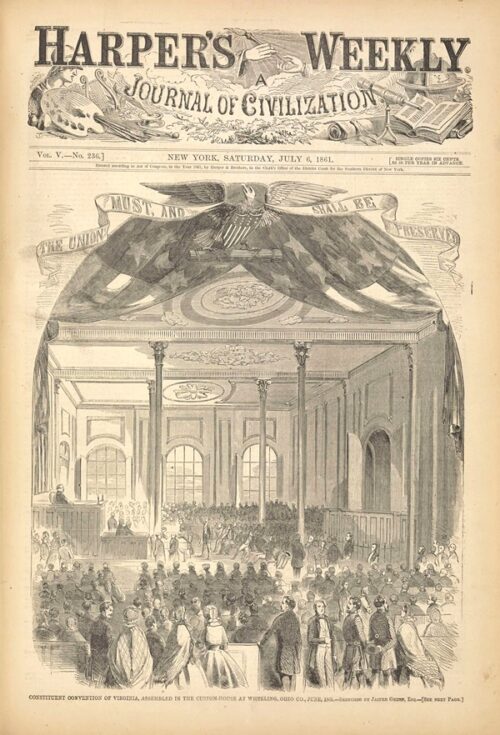

While Brown did not succeed in ending slavery in the area, the creation of West Virginia as a state was directly connected to the region’s opposition to the broader slave system. While delegates to the Richmond (Virginia) convention of April 1861 voted for an Ordinance of Secession to join the emerging Confederate States of America, a significant majority of those delegates from the northwestern part of Virginia opposed secession and the Confederacy. In two consecutive conventions in Wheeling, first in May and then June 1861, representatives from this region voted to oppose secession and to separate from the rest of Virginia if need be. As the early events of the Civil War continued to play out, these representatives held a third convention in Wheeling, this one a Constitutional Convention; between November 1861 and February 1862 that meeting drafted a Constitution for a new state, West Virginia, that was formalized with the Constitution’s ratification in May 1862 and admitted to the Union by President Lincoln in June 1863.

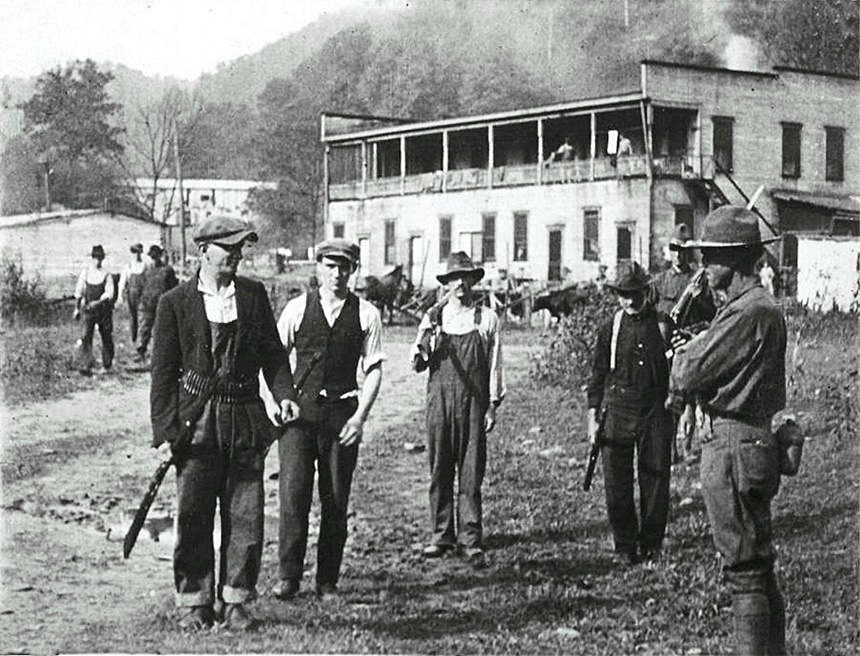

Almost exactly half a century later, West Virginia was the site of another, very different rebellion. The nearly decade-long conflict that came to be known as the West Virginia Coal Wars (or Mine Wars) began with an extended labor action by mine workers, the Cabin Creek and Paint Creek strike of 1912-13. Organized by the labor leader Mary “Mother Jones” Jones and supported by the national United Mine Workers (UMW), the strikers advocated for better pay, safer conditions, and an end to discriminatory practices such as the requirement that they shop only at company-owned stores. When the mining companies refused to negotiate with the striking workers and instead hired armed agents of the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to put down the strike, the workers moved into union-supported “coal camps” and settled in for an extended labor action.

The standoffs continued for years and culminated in one of the largest insurrections and most violent civil conflicts seen in America since the Civil War: the August 1921 “Battle of Blair Mountain.” Over a period of weeks, tens of thousands of striking miners fought a series of armed battles against thousands of lawmen and armed strikebreakers; the mining companies even hired private planes to drop bombs (many of them leftover from World War I) and poison gas on the strikers. When National Guard troops joined the forces opposing the strikers in early September, the conflict came to an end; nearly 1000 miners were indicted for murder and treason against the State of West Virginia, but most were acquitted. In the short term the conflict greatly weakened labor unions in the state, a trend seen across the 1920s in America; but in the long run the Coal Wars raised awareness and contributed to major victories for the United Mine Workers in and after the New Deal era of the 1930s.

Later in the 20th century and into the 21st century, one groundbreaking and influential West Virginia politician came to represent the state’s evolution on debates over civil rights. Robert C. Byrd (1917-2010) served three terms in the House of Representatives from 1953 to 1959 and then served as a Senator from West Virginia from 1959 until death in 2010, making him by far the longest-serving Senator in U.S. history (and the second-longest-serving member of Congress overall).

Byrd began his political career in the early 1940s by organizing a new chapter of the Ku Klux Klan in the town of Sophia, West Virginia, and in 1944 wrote to the segregationist Mississippi Senator Theodore Bilbo “I shall never fight in the armed forces with a negro by my side.” When he first ran for political office shortly thereafter, a successful 1946 campaign for the West Virginia House of Delegates, it was with the encouragement of Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard Samuel Green.

Yet by the end of his life, Byrd would call joining the Klan “the greatest mistake I ever made,” noting in a 2005 interview, “I know now I was wrong. Intolerance had no place in America. I apologized a thousand times and don’t mind apologizing over and over again. I can’t erase what happened.” His evolution on issues of race included both important individual actions, such as his efforts to integrate the U.S. Capitol Police for the first time since the Reconstruction period; and significant symbolic statements, such as his vocal support for the creation of the Martin Luther King Day federal holiday in 1983. As he told his staff at the time, “I’m the only one in the Senate who must vote for this bill.”

In his final decades in the Senate, however, Byrd stood in the way of another emerging civil rights movement, becoming one of the federal government’s most outspoken opponents of gay rights. In the debates over the Defense of Marriage Act, for example, he argued that “the drive for same-sex marriage is, in effect, an effort to make a sneak attack on society by encoding this aberrant behavior in legal form before society itself has decided it should be legal.” The West Virginia Senator became a key vote in support of that discriminatory federal law when it was passed in September 1996, one more way in which this small state has throughout its existence played a major role, for better and for worse, in reflecting and shaping American debates.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now