Since the Supreme Court handed down its decision over a decade ago in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, political analysts and voters have complained about the role of money in federal elections, frequently blaming the 2010 ruling. While the decision undeniably impacted the electoral landscape, the SCOTUS opinion in Citizens United is not actually ground zero for campaign finance reform. Rather, a 1976 decision by the Court in Buckley v. Valeo more essentially established the Court’s role in defining the issue for the next half century.

Before delving into the case, however, it’s useful to know the broad legislative history of the law. During the Progressive Era (roughly 1890-1920), fears regarding the influence of big business on elections resulted in the passage of laws in 1907 and 1910 banning corporate contributions to federal elections and forcing national parties and multi-state committees to disclose campaign contributions. Amendments followed in subsequent years that included expenditure caps, contribution limits, and increased disclosure requirements.

The laws, however, generally lacked any real enforcement mechanisms. No government agency assumed responsibility for enforcement, and the legislation contained so many loopholes they were functionally useless. President Lyndon Johnson described it as “[m]ore loophole than law,” which ultimately invited “evasion and circumvention,” two aspects of politics with which LBJ was not unfamiliar.

Controversies often fuel new campaign finance legislation, as Anthony Johnstone observed in 2014. In 1970, President Nixon vetoed the Political Broadcasting Bill, an effort by Congress to rein in media spending by campaigns. This, among other controversies, drew new attention to the need for better regulation. As a result, the House and Senate passed the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA), which Nixon signed into law in 1971.

FECA replaced the previous campaign finance laws passed earlier in the century. Among other measures, the Act created the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to enforce the law and eliminated the contribution and expenditure limits.

Three years later, driven by the Watergate scandal and with 90 percent of the public believing that campaign spending had careened out of control, Congress passed amendments to the 1971 act that added ceilings on campaign expenditures, limited campaign contributions, and established publicly financed presidential elections.

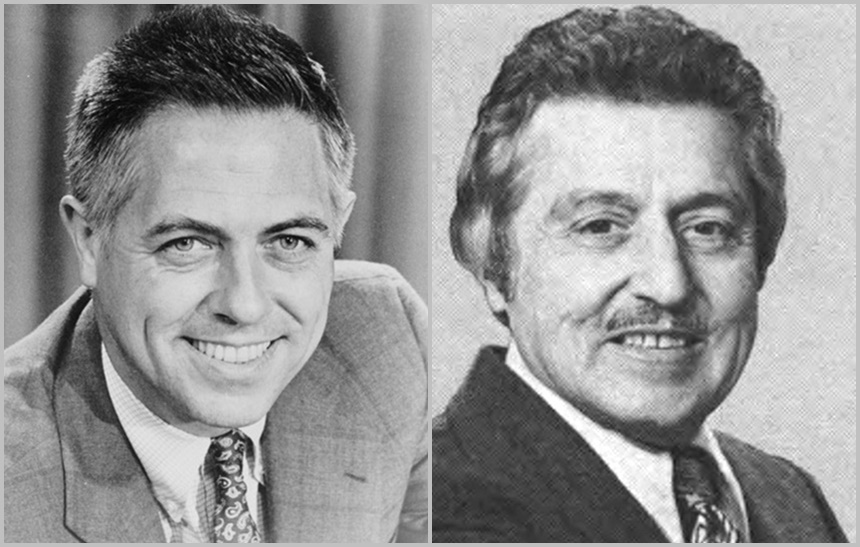

The 1974 law contained a provision allowing for judicial challenge, which FECA’s opponents wasted no time in utilizing. Big cases can create strange bedfellows; plaintiffs consisted of a motley crew of politicians and organizations, including conservative New York Senator James L. Buckley, former senator and liberal presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Libertarian Party, and the Mississippi Republican Party.

In contrast, due to U.S. Attorney General Edward Levi and Solicitor General Robert Bork’s doubts about the law, the Federal Election Commission sought its own defense. In most situations, government lawyers represent government agencies, but due to disagreement in the Solicitor General’s office, the FEC pursued additional representation, resulting in the odd symmetry of both First Deputy Solicitor General Daniel Friedman and Archibald Cox of Watergate fame being joined by fellow veteran SCOTUS lawyers Lloyd Cutler and Ralph Spritzer, arguing to uphold FECA. They defended the law on behalf of liberal senators Hugh Scott and Edward Kennedy and Secretary of the U.S. Senate Francis R. Valeo. The liberal non-profit organization Common Cause also took a lead role in supporting the law.

With the 1976 presidential election on the horizon, the Court was acutely aware of the ruling’s importance. Justice William J. Brennan noted the oddity of separate briefs by Bork and Friedman from the Solicitor General’s office, concluding that Bork’s submission “purported to give both sides, but it clearly leaned to invalidating the legislation,” and that “the favorite target” of his fellow Justices during the case was the “mass of worthless paper filed by [the plaintiff’s] counsel.”

The time crunch, public interest, and the political impact, along with the statue’s complexity and the legal issues at the heart of it made the “case one of the most difficult the Court has ever faced,” wrote Brennan. Chief Justice Warren Burger noted that press interest in the case nearly equaled that of United States v. Nixon.

Legal briefs for both sides exceeded 1,000 pages. One of Brennan’s clerks produced a 31-page bench memo attempting to capture the central issues at play, while Justice Harry Blackmun’s clerk submitted one over 60 pages. Both were longer than many draft opinions.

Oral arguments took place on November 10, 1975. One of the observers in the courtroom was Maurice Ford, who went on to a distinguished career as a Harvard law professor. Ford’s description captures the public interest in the case, as he witnessed “the long line of spectators on the steps of the marble temple” and described figures such as Cox, Kennedy, and Buckley as celebrities, going so far as to document a gaggle of teenage girls flocking to Cox after oral arguments. “I touched him! I’ll never wash my hand again!” one girl screamed — an aspect of the account more unbelievable than any part of the eventual ruling.

Ford noted, “[O]ne of the joys of an outstanding oral argument before the Supreme Court of the United Sates is to witness the carefulness and responsiveness of counsel.” Ford may have been impressed, but Brennan and his fellow Justices were not. Brennan described the general arguments as “ordinary” and not in line with the importance of the issues at hand.

The per curiam (collective, unsigned) decision issued by the Court on January 30, 1976, upheld provisions of the law, including keeping disclosure provisions, contribution limits, and public financing of presidential elections. However, they struck down others, most notably eliminating caps on expenditures by presidential and congressional candidates.

To put it bluntly, the Court equated money with speech, arguing that capping campaign expenditures violated the First Amendment. “Being free to engage in unlimited political expression subject to a ceiling on expenditures is like being free to drive an automobile as far and as often as one desires on a single tank of gasoline,” they wrote.

With the ruling, the size of individual campaign contributions remained capped, but now campaign spending was not. Unable to secure large donations with a single meeting with wealthy individuals, candidates had to constantly fundraise. The Court, legal scholar Jessica Levison argues, turned the law into “an engine for the glorification of money.” Justice Byron White presciently wrote in dissent, “Without limits on total expenditures, campaign costs will inevitably and endlessly escalate.”

Richard L. Hasen, Levinson, and others have argued that the Court’s interpretation privileges liberty over equality and in doing so, delivers neither. Without spending limits, the marketplace of ideas is “flooded with ‘speech’ produced only by the well-funded,” argues Levinson.

For example, within Congress, legislative skills have been swapped for fundraising talent. The most recent example of this might be Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene; the firebrand Republican arrived as a “disruptor,” but through her fundraising acumen has moved squarely into the party’s center. “Greene would have struck the [National Republican Senatorial Committee] as unpalatably extreme a few years ago,” journalist Joe Perticone wrote recently, but “[t]oday, as her fundraising email history suggests, she has a somewhat different profile …”

The numbers don’t lie. The 1976 presidential campaign eclipsed the 1972 campaign’s total of $137 million, costing $160 million. When accounting for political action committees and other fundraising organizations, overall federal election spending reached nearly $6 billion in 2008 and has continued to rise. The same is true of Congress. House candidates spent $44 million on campaigns in 1974; by 1982, they spent $174 million. Senators during the same period went from $28 million to $114 million, a 44 percent increase for the House, and a 70 percent increase for the Senate.

Other knock-on effects of the Buckley decision have impacted Congress. The congressional work week has shrunk since 1976. Representatives from the 1970-1972 two-year house session met 323 days in Congress, and by 2008 it had decreased to 250. By 2012 over 75 percent of Congress spent 40 weekends in their home districts raising money.

Most of these developments unfolded well before the 2010 Citizens United decision, though that’s also had an impact. Citizens United enabled PACs to take unlimited donations from individuals while also allowing corporations and non-profit entities to contribute to PACS and endorse a candidate as long they never directly coordinated with said candidate. Simply tracing the last three presidential elections demonstrates the decision’s multiplying effect. The 2012 exceeded $6 billion, 2016 went over $7 billion, and the 2020 presidential campaign exceeded $14 billion in spending.

One of the more famous scenes from the popular television show, Breaking Bad, involves one character telling the show’s protagonist, “No more half measures,” a reference to vacillation in the name of establishing a middle ground, which in the show had only led to more trouble. The same is true of Buckley. The Court would have been better off either wiping away most attempts at reform or enacting stricter regulations upholding expenditures, thereby favoring political equality.

Controlling expenditures would cap fundraising and enable legislators to focus on legislating. The current system, as both Republicans and Democrats can admit, is best at producing countless text messages and emails to potential donors asking for yet another small dollar donation.

In the end, the ruling in Citizens United served as extension of the more problematic origin story that is Buckley v. Valeo. In the cases heard between Citizens United and Buckley, the Court has stuck to its belief that money equals free speech, but left itself with damaging half measures that continue to plague elections to this day.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

No company, publicly or privately owned should be allowed to contribute any any political campaign or cause. Period. It should be illegal and the company should be fined if caught doing so. Now if owners, CEOs, Managers, Employees want to contribute individually, that should be their right with no recourse of any kind coming from the company ownership and management because of their political leanings and their giving to causes in which they believe in.