In the spring and summer of 1787, Philadelphia was abuzz with exciting new ideas and possibilities for the future, as a group of men — including George Washington, James Madison, and Benjamin Franklin — met to shape a new nation at the Constitutional Convention.

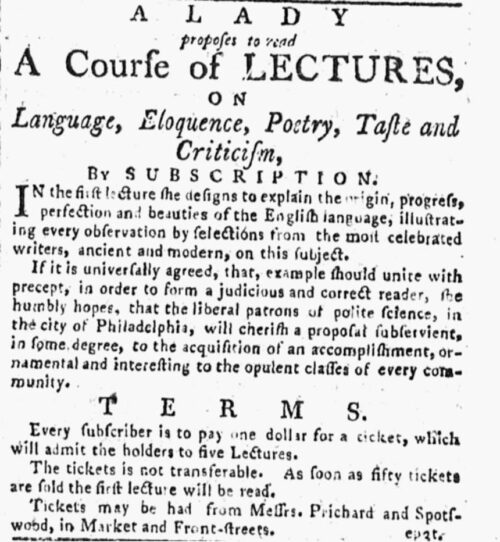

But other new ideas were crackling throughout Philadelphia. On April 2, 1787, an advertisement in the Philadelphia Independent Gazetteer offered something new for audiences. “A Lady Proposes to Read a Course of LECTURES on Language, Eloquence, Poetry, Taste, and Criticism,” the ad began. Subscribers could pay one dollar for a ticket to five lectures. That spring, Eliza Harriot became the first woman in the nation to lecture to public audiences.

As Harriot prepared her lectures, the city filled with new arrivals for the Constitutional Convention. On May 18, Philadelphia doyenne Mary White Morris took a group of female friends and General George Washington to hear Harriot’s lecture on elocution. Morris and her husband had become good friends with the Washingtons during the American Revolution. Now, the two men had both been named delegates for the Constitutional Convention, expected to begin any day, once enough delegates arrived.

The matter of government was not the only thing on peoples’ minds that year. Some Americans were starting to consider ways to improve life for disenfranchised people within the nation. In Philadelphia, the Free African Society had formed in April, devoted to the prospect of supporting people recently freed from enslavement. Dr. Benjamin Rush created the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons, the nation’s first reform effort focused on the incarcerated. And then there was Harriot’s lecture series, which became a prelude to larger discussions about what women should be and do.

Women in Philadelphia had long shaped discussions about the new nation. When the Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in the 1770s, many of those delegates found themselves at the home of Elizabeth Powel and her husband Samuel. Elizabeth Powel’s events were known as intellectual and political spaces. There, guests spoke and debated about political issues, the new nation, and philosophy.

After the War of Independence, the Powel home continued to see guests like John and Abigail Adams, physician Benjamin Rush, George and Martha Washington, and the Marquis de Lafayette. Powel exchanged letters with George Washington regularly. He came to view her as someone whose advice he trusted. In late 1792, Powel counseled the president that he should stay in office for a second term, which he did.

Other well-known women of the time included Anne Willing Bingham (Elizabeth Powel’s niece) and Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson, a poet whose gatherings included other writers and figures like Dr. Rush. Women in late 18th century Philadelphia lived in a place where they had space to think and converse. This was particularly true for women of a certain social class, who had the time to do so, as well as the political and economic connections.

It was in the spaces where society and politics met that the men and women connected on more than just domestic issues. Men conversed with women like Elizabeth Powel and Mary Morris; Washington would, in the years ahead, correspond with Eliza Harriot as well.

While the delegates of the Constitutional Convention pursued one patriotic project, another was also just beginning. On Monday, June 4, 1787, the same day the Constitutional Convention delegates were debating the size of the executive branch, half a mile away a man named John Poor established the Young Ladies’ Academy of Philadelphia.

This would be an institution for young ladies of privilege, a space to cultivate women like Elizabeth Powel. Dr. Benjamin Rush (who, among his many other activities, was also a signer of the Declaration of Independence), made that connection explicit on July 28, 1787. That day, he dedicated a speech at the Young Ladies’ Academy to Elizabeth Powel. It was a speech that would have a long life, partially titled “Thoughts upon Female Education:”

A philosopher once said, “let me make all the ballads of a country and I care not who makes its laws.” He might with more propriety have said, let the ladies of a country be educated properly, and they will not only make and administer its laws, but form its manners and character. It would require a lively imagination to describe, or even to comprehend, the happiness of a country where knowledge and virtue were generally diffused among the female sex.

In 1792, the state of Pennsylvania granted the Young Ladies’ Academy a charter. This gave it government recognition, a seal of approval something like state accreditation today. It did not come with funding, even though the state gave money to the boys’ schools it chartered. While other girls’ schools would open in Philadelphia in the years that followed, Pennsylvania did not grant charters to any additional girls’ schools until 1829.

The inaugural class of 100 students at the Young Ladies’ Academy came from all over the young country, as well as from Nova Scotia and the West Indies. Classes included reading, writing, grammar, and math, but also history, rhetoric, and geography. Dr. Rush taught the first chemistry course in the nation for women, with seven lectures on general chemistry principles and five more on how to apply those in the home. Education at the Young Ladies’ Academy was both aspirational and practical.

While the Young Ladies’ Academy of Philadelphia did not educate all women, those who studied there received a new type of education that many saw as important. Schools for young women opened across the United States between the 1790s and the 1820s. While not all had access to such schools, their existence shows that some Americans were becoming deeply invested in the idea of educating young women.

On December 18, 1794, student Ann Harker delivered the salutary oration at the Young Ladies’ Academy’s commencement exercises. Speaking in part on the subject of women’s education, she argued, “In this age of reason, then, we are not to be surprised, if women have taken advantage of that small degree of liberty which they still possess, and converted their talents to the public utility.”

Her classmate Ann Negus delivered the valedictory address that day, striking a similar note. Negus saw a connection between patriotism and the education she received. Speaking to the board, classmates, families, and First Lady Martha Washington, Negus argued that educating young women was good for women and their nation. “The real patriot shows regard for his country [by executing] those measures which he conceives really conducive to the welfare of mankind….This seminary, in particular, has furnished society with some of its brightest ornaments.” The act of creating a school for young ladies, she emphasized, was patriotic itself, and fitting in such a changing age.

The events of the Constitutional Convention and the creation of the United States Constitution tend to take center stage in the story of 1787. Yet even as the 55 men came and went during their five months of deliberation, theirs were not the only voices shaping the nation. Eliza Harriot’s lectures found a home in Philadelphia because it was a community where women’s voices and ideas mattered. The opening of the Young Ladies’ Academy became successful because of the community around it. The summer of 1787 fostered not only the ideas of a new nation, but new ideas of what women’s lives could become in that nation.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

These women were/are remarkable for what they set into motion in getting our new nation off to the best start possible. Working together with the men of power for the mutual goal of the common good for the people.