This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On each of the last two Sundays, I’ve dropped the first two episodes — Innings — of my new narrative history limited podcast: The Celestials’ Last Game: Baseball, Bigotry, and the Battle for America (the remaining seven Innings will appear each Sunday through October 27th, right in the midst of the World Series). This podcast was directly inspired by two of my prior Considering History columns: this one from May 2020 on the Celestials baseball team; and this one from April 2022 on early baseball histories. So I’d really love for you all, my treasured Saturday Evening Post readers, to check out the podcast, follow along with the stories of the Celestials, Denis Kearney, and much more over the next seven weeks, and share your thoughts with me while you do!

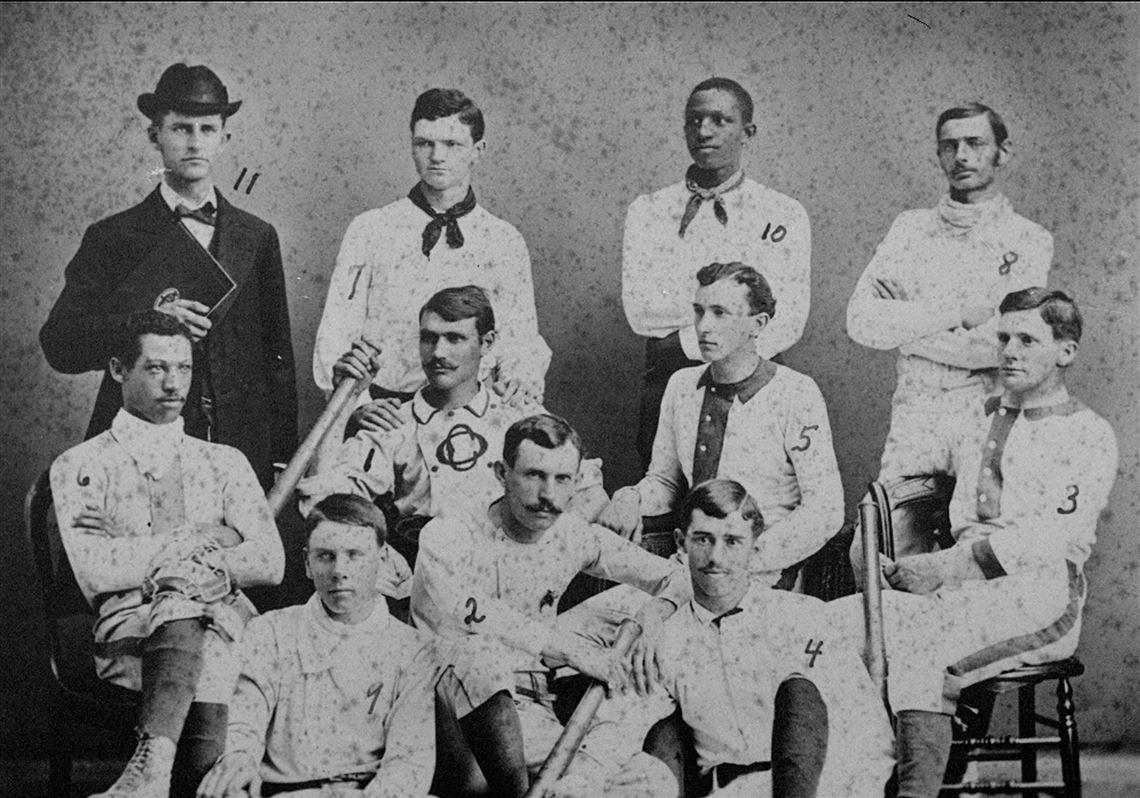

In honor of that new podcast and the tragic yet triumphant sports story at its heart, I wanted to dedicate this column to a few examples of 19th century baseball players who also exemplify that duality. These athletes of color embodied the possibilities of baseball and American professional sports in their early years, yet also experienced the systemic prejudices and limits that sports can challenge and sometimes transcend but can never entirely escape.

In 1884, a pair of African American brothers became the first openly Black athletes to play for a Major League Baseball team (recent sports historians have identified William White’s 1879 season as the first by a Black player, but White passed as white throughout his career and life). Moses Fleetwood Walker (1856-1924) and Weldy Wilberforce Walker (1860-1937) had grown up in Mount Pleasant, Ohio, a haven for escaped and former enslaved people, and attended one of the first integrated high schools, Steubenville High. Both also attended Oberlin College and starred on their baseball team, with Moses in particular gaining enough renown for his hitting as well as his skills at the all-important position of catcher that he transferred to the University of Michigan.

In 1883, Moses left Michigan and signed with an independent league team, the Toledo Blue Stockings of the Northwestern League. With his contributions at the plate as well as his positive effects on the team’s pitchers — a writer for Sporting Life called Walker and pitcher Hank O’Day “one of the most remarkable batteries in the country” — the Blue Stockings had a successful enough season to transfer to the majors, joining the American Association for the 1884 season. When spots opened up due to injuries, Moses convinced the team to add his brother Weldy for a handful of last-season games as well. Unfortunately, the team was facing significant financial pressures, and both Walker brothers were cut at the season’s end.

Along with those economic realities, racism might have contributed to Moses Walker’s brief major league career. When Toledo played the Chicago White Stockings, for example, Chicago’s future Hall of Fame manager Cap Anson is alleged to have said, “We’ll play this here game, but won’t play never no more with the n****r in.” Moses faced such blatant racism from peers and fans alike, not only through another five seasons until his 1889 retirement, but also after retirement, when he was attacked by four white men in Syracuse. When he killed one of them in self-defense, he was charged with second-degree murder (but fortunately found not guilty).

Moses did not let these struggles and tragedies define his story, and by the turn of the century he and Weldy were successful Ohio businessmen, owning together Steubenville’s Union Hotel and the Opera House movie theatre in Cadiz. In 1902 they also founded and edited for a short time a newspaper, The Equator. In its pages Moses began to explore ideas of both Black nationalism and the possibility of emigration to Africa that he expanded in his 1908 book Our Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present, and Future of the Negro Race in America. But Moses never left the United States, and in any case his legacy as the first Black professional baseball player deserves as much remembrance and recognition as Jackie Robinson’s.

A few years after Walker’s retirement, a Native American baseball player made his own brief but impressive imprint on the evolving major leagues. Louis Sockalexis (1871-1913), nicknamed “the Deerfoot of the Diamond,” was born on the Penobscot Indian Island Reservation in Maine. He achieved athletic acclaim at a very early age, demonstrating his cannon throwing arm for crowds at the nearby Bangor Race Track when he was a teenager. In his early 20s he was playing for an independent league in Maine when members of the Holy Cross baseball team recruited him to join that college; as a student-athlete there he excelled at football and track as well as baseball, and then transferred to Notre Dame where he gained even more recognition.

In 1897, while Sockalexis was at Notre Dame, the team played an exhibition against the major league New York Giants at their home stadium, the Polo Grounds. Despite facing extensive racist taunts and chants throughout the game, Sockalexis homered off of the Giants’ future Hall of Fame pitcher Amos Rusie (against whom Sockalexis would likewise find major league success). Sockalexis would hear such racism from fans at every stage of his playing career, including choreographed “war dances” from hostile spectators. So too would the members of his community who supported him, as was the case at the Polo grounds in 1897, when a delegation of Penobscots who traveled to the game were insulted by a group of racist sportswriters.

Such struggles took an early and inescapable toll on Sockalexis; before he could graduate from Notre Dame, he was expelled for the alcoholism that would eventually consume his life. His baseball talents remained undeniable, and in 1897 he signed a professional contract with the Cleveland Spiders of the American Association major league. Unfortunately, he injured himself badly in a drunken accident mid-season; although he still went on to get nine hits in his next 18 at-bats, and to end that first season hitting .338, his skills were never quite the same after that accident. He played with Cleveland for two additional, less remarkable seasons, and then with a number of minor and independent league teams until his retirement in 1907. He would die of a heart attack while cutting down a Christmas Tree at the tragically young age of 42.

Like the ten Chinese American players on the 1870s Celestials semi-pro baseball team at the heart of my podcast, these athletes of color embodied the best of 19th century baseball and sports in America in an era when they were just beginning and, across semi-pro and independent as well as major leagues, offered possibilities for inclusion. All these inspiring athletes deserve a central place in our collective memories of the best of what we’ve been and still can be.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks so much, Mark! Just wanted to note that this is the only Sat Post column of mine (for now at least) which will deal with these particular subjects, but my podcast drops new Innings each Sunday for the next six weeks (three are out already), here:

https://americanstudier.podbean.com/

Each Inning is about 30 minutes long, so hopefully a way to build on the column with lots more layers! Thanks,

Ben

Fascinating article on the contributions these players made in the early years of baseball. Hard to imagine the struggles each individual went through not only on the baseball field but in everyday life. Was overjoyed to learn that the African American brothers went on to be successful businessmen later in life. Saddened to learn that the Native American dealt with alcoholism which was probably a contributing factor to his heart attack and subsequent death. I look forward to reading this authors installments all the way through October. Great reading!