The standards we use to analyze films for “appropriateness” have evolved in the last century. In the 1900s, there was no such thing as a PG-rated movie or a “Viewer Discretion Advised” warning. In fact, movies weren’t categorized at all. But in the early 1900s, movies started to be monitored with a harsh eye that cut vast sections from films before they made it to the theater, and other films were banned entirely.

Movies spread throughout the U.S. during the turn of the century. While many audiences were enthralled by the new means of entertainment, some critics believed that the popularity of films, especially those featuring law-breaking, was responsible for the growing rates of crime. In particular, the governments of several major cities cast the blame for acts of illegality at the feet of film producers.

Chicago was the first city to take action against the film industry. In 1907, the city enacted a local government code requiring film distributors to submit their movies to a board for review. Many cities around the U.S., including New York City, followed suit over the next couple of years. Since each city had different ideas of what was immoral, many different cuts of the same film could be found in theaters around the country.

Chicago’s own Film Censor Board, run by the Chicago Police Department, was one of the most notorious of the movie monitors. Throughout its tenure in the film oversight business, which began with its formation in 1907, the board made many strange and arbitrary choices and let itself be corrupted at almost every turn. And yet it laid the groundwork for the movie ratings we know today.

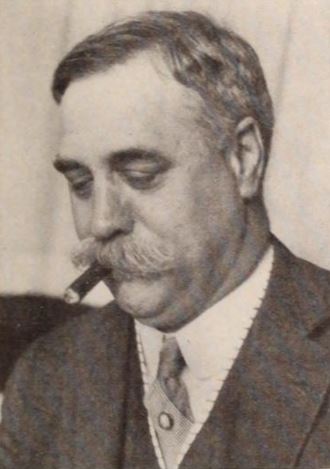

In 1913, Chicago P.D.’s Second Deputy Superintendent Major Metellus Lucullus Cicero Funkhouser began serving as the city’s chief censor. Funkhouser’s team, which included several ex-convicts (who had been hired in the hope that they could return to being productive members of society), combed through hundreds of films between 1913 and 1918, according to the Chicago Tribune. After viewing the films, they wrote reports to tell filmmakers which sections were inappropriate and needed to be removed. The filmmakers then made the required changes or risked having their film banned from Chicago theaters.

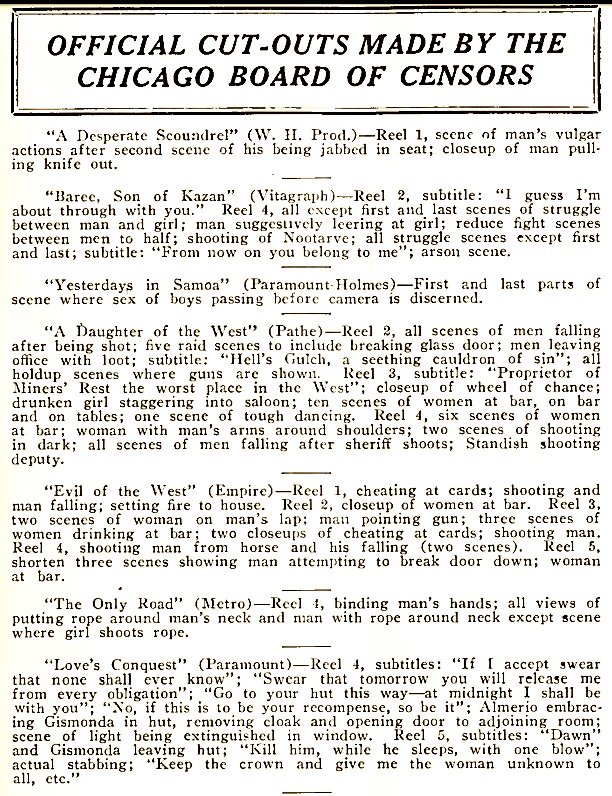

The board used many topics as evidence for banning a film, and Funkhouser quickly gained a reputation for being harsh when it came to content. He even chose to remove dancing from all films. He told the Exhibitors Herald in 1918 that showing dancing was dangerous because it encouraged teenagers to go to dance halls, which were “the source of much crime and immorality.”

While the dancing restriction seems strange today, some of the things the board flagged would still be censored or age-restricted in modern cinema, including sex, nudity, and large amounts of violence.

However, many of the board’s reasons for banning material stand out today. Among their strangest decisions were the restriction of: Awake, America, Awake (protests and political criticism), Marked Cards (a man cheating at cards), Shackled (a woman who was not married), Chains of the Past (a theft), The Ordeal of Rosetta (women in a bar), Selfish Yates (the word “hell”), The House of Hate (fire), Baree, Son of Kazan (a boxing match), and Smashing Through (a bathroom). Films were also banned for depicting characters who were Black, Hispanic, Asian, or Indigenous, and for showing people of different races interacting.

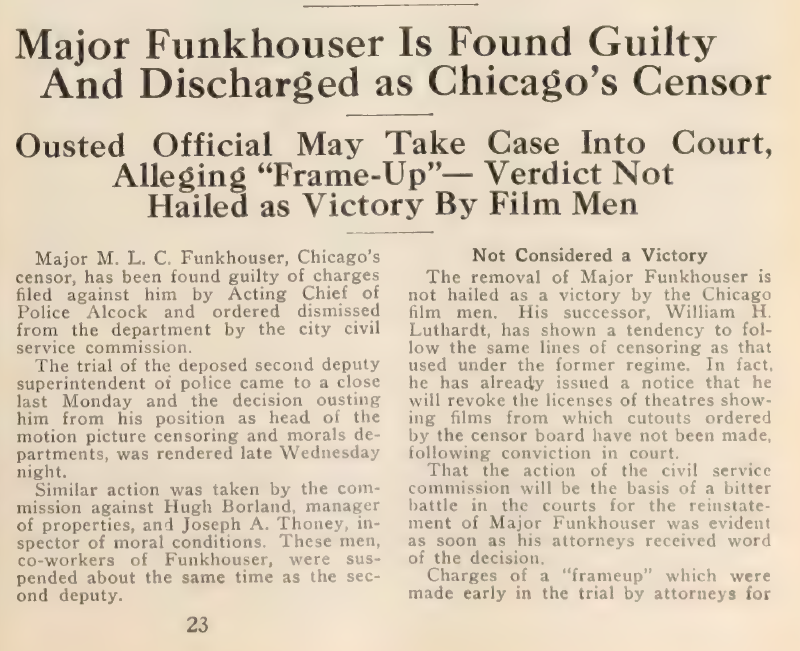

In addition to implementing harsh restrictions, Funkhouser had also hosted parties at the censorship office, in which the scenes that had been banned from movies were strung together and shown as extended “naughty features.” This hypocritical practice caused many citizens to file complaints, which led to an investigation by the Chicago Civil Service Commission, according to the Chicago Tribune. After the investigation had concluded, the CCSC filed 41 civil charges against Funkhouser. Amongst the charges were failure of supervision, mismanagement of funds, and conduct unbecoming a police officer.

However, the charges against Funkhouser didn’t just relate to his work as chief censor. They also covered the vast corruption within the censorship office. In their filing, the CCSC alleged that Funkhouser had knowingly allowed his employees to commit crimes, while also ordering his employees to stalk public figures such as the Chief of Police.

Funkhouser and the rest of the board denied the accusations, alleging that he had been framed. Funkhouser appeared in court on June 24, 1918. Ultimately, Funkhouser was convicted and dismissed from the office of Chief Censor. He died two years later.

After Funkhouser’s dismissal, the censorship board’s role diminished. The position of chief censor was retired permanently, while the board lost its power to national film review organizations, including the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, established in 1922, which was followed by the Production Code Administration (PCA), established in 1934, which was followed by the introduction of the content warning banner “For Mature Audiences Only,” which was first used on the poster for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

The Supreme Court decision Freedman v. Maryland in 1965 defanged movie censorship laws. In 1968, the PCA was formally retired, and the Code and Rating Administration was established. In 1972, the Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. California that obscenity’s definition in film was in part dependent on community standards. Thus, the court ruled that films could avoid sweeping censorship as long as they were appropriately categorized and adhered to the rules of a specific rating. These events led to the modern rating system, with the General (G), Parental Guidance Suggested (PG), Parental Guidance Strongly Suggested (PG-13), Restricted (R), and Adults Only (X) categories. The “No One 17 and Under Admitted” (NC-17) rating replaced the X rating in 1990. Despite the many social and legal changes, Chicago’s film censorship board would not be dissolved until 1984.

None of these vast changes in film history might have happened if it weren’t for the Chicago Police Department and its infamous censorship board.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

And now we have Ron DeSantis and his Florida book bana

Being a resident of downstate Illinois, it doesn’t surprise me to hear of the corruption of Chicago Censorship Board during the early 1900’s. The downstate nickname for Chicago is ” Corruptville.” This is evident by the fact that so many of our past governors and politicians that are in prison or have served time for corruption are from Chicago or that area with a few exceptions.

Some of the sex scenes in today’s movies are too provocative and even border on obscene. Where are today’s censors when needed?

Also, the violence, blood, and guts in many of today’s movies are too gory and sickening. Again, where are the censors when needed?

The bottom line is this: The majority of today’s movies are outright disgusting and unfit for anyone to watch. We are a sick society.

Wow! This IS an eye-opening report on a multitude of levels concerning the intertwinement of early 20th century film censorship and corruption otherwise, having a surprisingly long reach into the later sections of it. Chicago and crime are synonymous with each other (then and now) probably more than almost anywhere, so what finally happened with Major Funkhouser came as no surprise.

I… had no idea that there were various censored/edited versions of the SAME film around the country, per paragraph 3 here. Even being aware of films being edited/censored, this never occurred to me. I figured once the determination had been made, they’d all be uniformly modified in following suit. Evidently not.

Movies of the early 30’s had things snuck into them that wouldn’t be allowed later in the decade. I love these ‘Pre-Code’ films, partly seeing what I can find that was later not allowed. On a side note, the quality of the picture and sound quality during this decade went from just past the Silent Era, to the best it would ever be. We no longer have color on the level of ‘The Wizard of Oz’ from 85 years ago. We DO have ugly “non-color” color now though.

I didn’t know the “For Mature Audiences Only” was first used on ‘Virginia Woolf’. I can certainly understand

why. It wouldn’t be necessary today because it would/could only be made for a narrow sophisticated audience on Starz, FX, etc. The masses are, well you know.

An interesting film fact was when Olivia de Havilland did a warning ad to viewers not to see “Lady In A Cage” (1963) alone. ‘You will be shocked, you will be terrified’ and more. She wasn’t kidding. I saw it for the first time in 2020 on Hulu. It IS a shocker, and then some. Haven’t been able to find it online again though, in several years.