Have you heard about the “Math Wars?” It’s a term used to describe periodic conflicts about the K-12 mathematics curriculum and methods for teaching math in our classrooms; examples of programs that have come under scrutiny are New Math and the Common Core.

The latest set of skirmishes involves Jo Boaler — a Stanford professor who has spent her career studying more equitable models for math instruction and advocating for curricular reforms known as the California Mathematics Framework — and those who believe Boaler’s research is ill-founded or even misleading. Some of these battles have been intense, with accusations of professional misconduct.

One particular hot-button issue from the Math Wars that affects all of us who care about education more broadly is the connection between math anxiety and timed tests. Boaler has made the claim that “timed tests cause math anxiety.” Her detractors counter that timed tests do not cause math anxiety. Both groups miss the point. To understand why, you need to understand what math anxiety is.

Anxiety of any kind can be detrimental for learning (as I discuss in my book on the science of learning). But math anxiety is a specific condition, an academic-related disorder that, according to the American Psychological Association, “causes distress, disrupts the use of working memory for maintaining task focus, negatively affects achievement scores, and potentially results in dislike and avoidance of all math-related tasks.” Students who struggle with math anxiety face both short-term and long-term obstacles in school if they are not able to resolve it with help from teachers and parents.

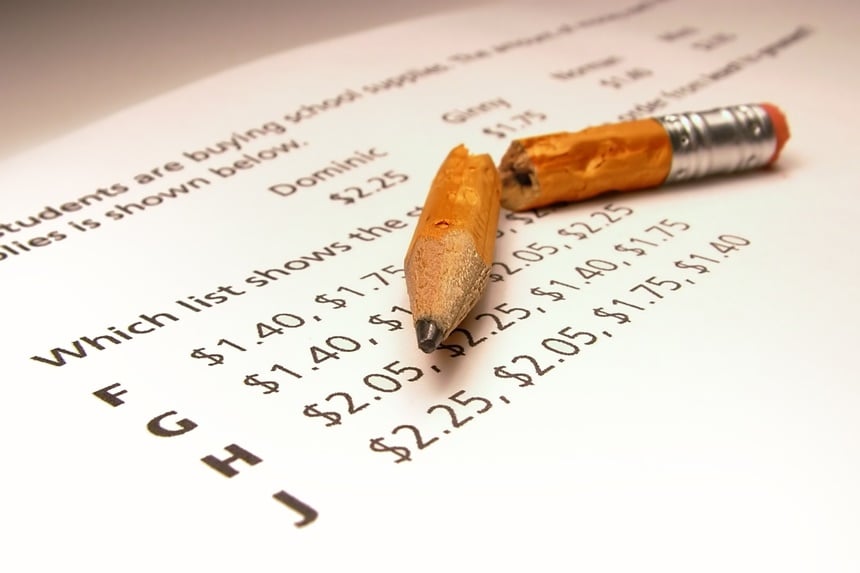

The link between math anxiety and timed testing has been hotly debated by both educators and researchers, primarily because this type of test is used often, especially in elementary schools, to help students develop fluency and automaticity — two key building blocks for success in math. But the experience of being timed, particularly but not exclusively when the tests will receive a grade, is often fraught for many students. Remember those quizzes where you had to solve as many multiplication problems as possible in less than a minute? I sure do.

The reason Boaler and her adversaries miss the point on timed tests is because they are arguing about cause and effect as if that were a simple relationship. You would be hard pressed to find any prudent education researcher (or any social scientist more generally) who would tell you that we can find a single cause for a specific phenomenon. Human beings are deeply complex, and there are too many variables at play when we are trying to study something as multifaceted as math anxiety, so it is nearly impossible to isolate one factor as the sole “cause.”

So, it is fair to question Boaler’s claim about timed tests and math anxiety, but it is also disingenuous to imply, like her detractors, that timed tests have nothing at all to do with math anxiety. In fact, there is important evidence to suggest that timed tests either contribute significantly to or interact powerfully with math anxiety. We are still learning so much about the scope of the problem, but I think we can say two things with confidence: 1) timed tests are not innocent bystanders in our math anxiety dilemma, and 2) people who are shaping our national conversation about teaching mathematics feel the need to claim certainty on this topic in one direction or another.

Why? I think this issue is a proxy for many other debates about teaching. Some, like Boaler, are asking us to radically reimagine traditional practices so that students who have not historically succeeded in some environments can reach new levels of achievement. Others want us to be more cautious so that we do not eliminate useful tools if they only require some additional tuning in order to continue being beneficial. Research is vital for these conversations, but it will never provide us with complete, unambiguous answers.

Like everything else in education, it’s complicated, and when it comes to our work with students, we should always err on the sides of concern and empathy. There are a lot of ways to help children learn math. If timed tests raise a caution flag, maybe we should look to other strategies. At the very least, we shouldn’t be afraid to question the use of particular approaches, despite what the Math Wars might lead us to believe.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

My Intro to Education teacher read the Saber-Tooth Curriculum to our class. It was a topic of discussion throughout the semester. It is the best way to understand that teaching is complicated and no one approach works all the time.

In this case the author seems to understand both sides of the argument laid out in the Saber-Tooth Curriculum (use a new curriculum or stick with the old curriculum), but then the author inserts the stupid ideology about erring on the side of concern and empathy. This leads to no kids learning because you’re afraid you might hurt them.

The timed method works great in certain situations and is a great and beneficial tool for a teacher. If it’s overused, it could lead to problems, but in most instances you are going to get most of the students up to the proficiency needed in a relatively short time. And those students will feel great for their new proficiency. Additional methods could be used for the few students with different needs, but a good method shouldn’t be set aside because it might cause discomfort to some students.

This is an excellent follow-up (of sorts) to your ‘Origin of Grades in American Schools’ feature a few months ago, Joshua. Here, I can believe Ms. Boaler’s well researched findings on math anxiety would result in ‘the system’ wanting to punish her for going against their status quo.

Her research per the paragraph 3 link ‘claim’ make the most sense, but I’ll give her detractor Greg Ashman in ‘counter’ here respect in his effort to counter her, but no sale. The remainder of your article makes the most sense intellectually, psychologically, emotionally and more with how timed math tests can absolutely cause anxiety with math, and with learning period, in other subjects as well.

Timed tests have raised a red caution flag, and other strategies definitely need to be looked at. This could/should include looking at schools in (say) different European countries and see what they’re doing that works and what doesn’t. The American educational system overall, especially K-12, needs to lower the temperature of failure fear drama placed on students, and maybe have them be classrooms instead of boiler rooms.