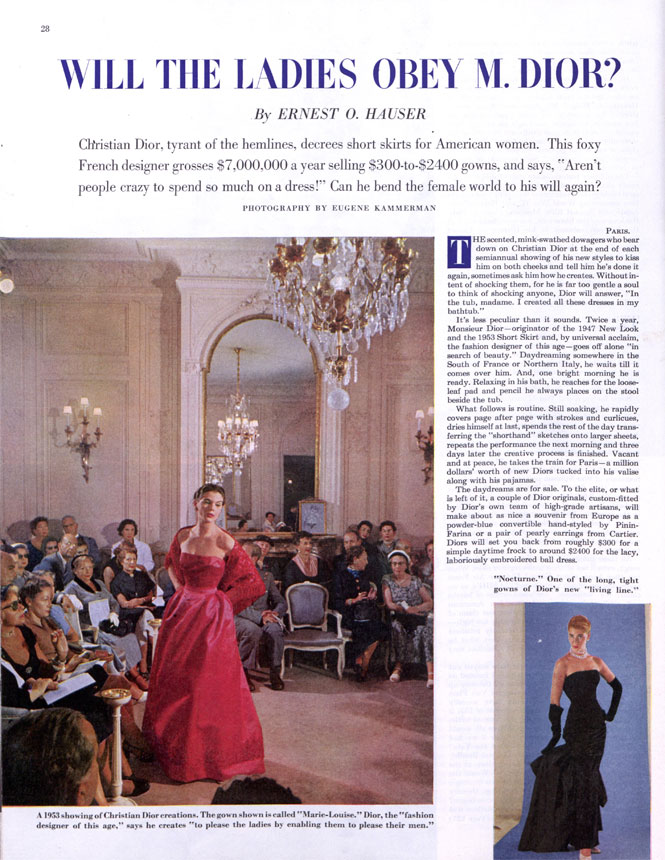

In 1947, as the world was still rallying from the trauma of World War II and adjusting to the new Cold War order, a young designer was causing his own excitement in the fashion world. Presenting his first independent collection, the then relatively anonymous Christian Dior almost single-handedly revolutionized couture and reasserted the prominence of French design.

Coined “The New Look” by Harper’s Bazaar’s American editor, Carmel Snow, Dior’s designs celebrated femininity and lavishness and marked a clear break from the prevalent styles of the time. The collection was characterized by a return to a Victorian feminine ideal of an hourglass silhouette, a molded torso with a cinched waist, an emphasis on hips, and a very full and longer skirt padded with petticoats.

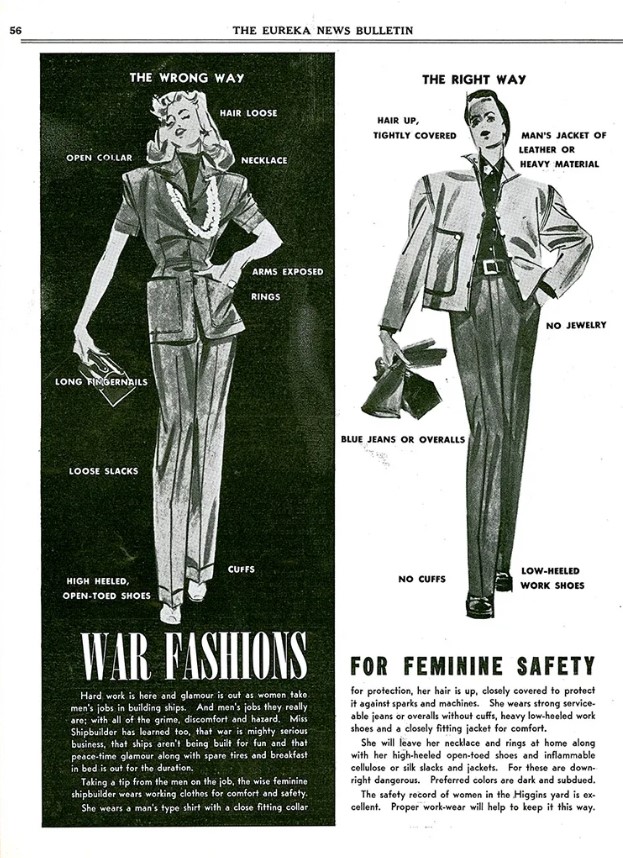

Dior did not just offer a new look, but also, as Snow declared, redefined “the essence of femininity.” The New Look broke away from World War II utilitarian styles that celebrated the mobile, on-the-go woman, and instead reflected the postwar conservative turn that pushed women back into traditional gender roles and espoused renewed ideology of domesticity.

Abandoning the heroism and feminist spirit of the American “Rosie the Riveter,” Dior’s ideal woman was hyper-feminine and chic. Her clothes were not meant for work or a career, but for luxury and leisure. With models such as the “Bar Suit” and “Chérie,” Dior imagined the ideal woman as a beautiful object to admire.

Dior’s New Look became a fashion and commercial success, making Dior, almost overnight, one of the most prominent designers of the century. Celebrated over the pages of the major women’s magazines, his designs ushered in a new era in fashion.

However, while the New Look certainly had its fans among the echelons of the fashion world, they tended to overestimate its reception among American women.

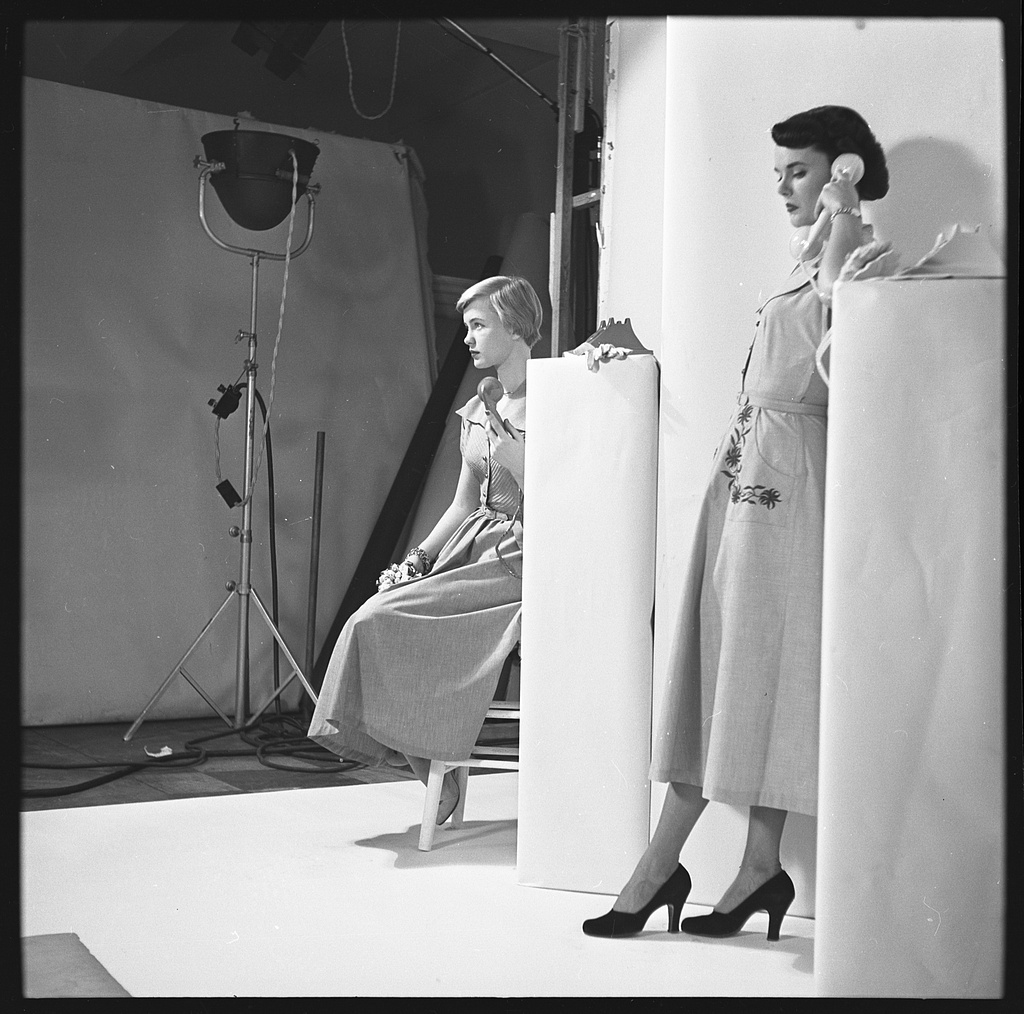

Indeed, for the majority of women who spent the war years dressed in the sportswear styles of the 1930s and early 1940s, the New Look did not offer an appealing alternative. Sportswear fashion was grounded in comfort, versatility, and accessibility. It was comprised of knits, everyday dresses, suits, and separates that epitomized what Lord & Taylor President Dorothy Shaver coined as the “American Look.” And like the New Look, the American Look also celebrated a specific type of femininity, but one that was modern, independent, and liberated.

All across the country, women revolted against Dior’s new styles, showing unwillingness to give up the freedom and comfort that the war styles provided them. In Texas, women banded together to form “Little Below the Knee” clubs to protest Dior’s designs, declaring “the Alamo fell, but our hemlines will not!” And in Berkeley, California, wives of veteran G.I. students formed WOWS (Women’s Organization to War on Styles), organizing demonstrations while carrying signs declaring “United We Stand, Divided They Fall.”

These women claimed that the New Look was an attack on their freedom and on democracy. The design hampered movement and was difficult to wear, and the use of extra cloth made it more expensive than previous fashions. Some argued that the problem was not so much at the length of the skirts but with their width that made it impractical to the life of the modern woman.

American fashion designers also joined the critics. Sportswear designer Bonnie Cashin, who was in Paris at the time, lamented that the New Look distorted the female form and ignored women’s needs. And Jo Copeland, another American sportswear designer, announced in 1947 she would no longer travel to Paris for inspiration.

Indeed, undeterred by Dior’s ascendence, the American fashion industry was determined to protect its war years’ reputation and to continue designing clothes in the spirit of the American Look. The 1947 collection of Saks Fifth Avenue did not include any models inspired by Dior’s New Look. Questioning Dior’s Success, Sophie Gimble, Saks Fifth Avenue’s house designer, told Time magazine that American women would never go back to wearing uncomfortable styles: “Even if they do like this tight waistline, how many are willing to go through the agony to get it? I put on one of those new corsets and after 15 minutes I had to take it off. I’ve never been so uncomfortable in my life.”

In the face of resistance, even Dior changed course. He accommodated his designs to the American market, reducing the fullness of the skirts and the number of hooks, and in later collections even added pockets. In 1948, he shortened the skirt, and in 1949 he abandoned the corset. By 1950, Dior dropped the New Look in favor of slimmer silhouette and shorter skirts.

Although Paris would regain its fashion leadership after the war — much thanks to Dior — the popularity of sportswear styles among American women proved that the domestic industry was a worthy opponent, and that women themselves are not dupes who will follow any designer’s whim.

In 1955, sportswear would receive its ultimate acceptance into the mainstream when Claire McCardell — the designer most associated with the American Look — was featured on the cover of Time magazine. The same year, McCardell also grabbed the attention of a young journalist named Betty Friedan. Celebrating McCardell as “the Gal Who Defied Dior,” Friedan pointed to liberating and feminist elements behind American sportswear styles.

While today the name Dior is far more familiar than that of McCardell, her legacy of designing comfortable clothes that suit the active lifestyle of women has won the day. Much more than wearing the feminine silhouettes of the New Look, women today are embracing athleisurewear. In fact, McCardell’s most two prominent design inventions — ballet flats and leggings — have become a staple in women’s wardrobes.

Dior’s New Look certainly deserves its place in fashion history. It has charted a path for French fashion and changed couture. But alongside it, we should also remember its alternatives, and the millions of women who chose a different path, adopting styles that conveyed their independence and freedom.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you Bob. I’m glad you liked the article. Maybe in the future I’ll also write about the mini, an interesting story there as well, your mother would have appreciated it.

Really good article on a topic not so much in my wheelhouse otherwise. I never knew the lofty Christian Dior was taken down a few pegs by the American woman who’d gotten used to (and liked) the more utilitarian and practical clothes they’d gotten used to. He was sent back to the drawing board in the late 40’s to make alterations.

My mom had a particular disdain for the miniskirt much later, in the soaring ’60s. Also frosted hair and go-go boots. But when Barbara Cowsill (her age) took to the looks, mom did too. She was at her best when she contradicted herself; no question about it.