In the past few months, anxiety around artificial intelligence, especially in the form of large language models such as ChatGPT has reached a fever pitch. One example of AI’s potential impact is in the realm of information, news, and journalism. People are worried about the potentially negative impact of deepfakes and other AI-generated disinformation, with ramifications for the fate of democracy and free societies everywhere.

At the heart of these concerns is the idea that machines — often without moral/ethical guidance and sometimes nudged, or even more explicitly, directed by nefarious human agents — really can’t be trusted with the complex, difficult truths about our reality that often defy easy solutions.

To put it another way: Can we trust algorithms to tell true stories about our world?

Worries about technology and artificial intelligence (sometimes broadly referred to as “automation”) and its impact on storytelling and journalism have been around since the early 20th century, when editors conjured the specter of reporter robots. Actual use of technology in these fields dates back to the 1960s and 1970s, with the first generation of word-processing tools. This included very early efforts at automated writing, such as spell- and grammar-checks, as well as the introduction of software-driven processes for copy editing, layout, and production.

Later, AI — more or less as we understand it today — was discussed by news workers in journalism trade publications in the 1980s and 1990s and through the 2000s. This era saw the full computerization of the newsroom, as well as the introduction of the civilian internet and its adoption by the news and media industries.

When thinking about the legacy of AI anxiety, context is key, and knowing where these fears have come from might help news consumers today and tomorrow make smart choices about when to trust the machines and software that are part of our lives and will be for the foreseeable future.

The Advent of Technology Anxiety in the Newsroom

During the Great Depression, as journalism jobs and newspapers struggled to survive, Marlen Pew, an editor at the newspaper industry trade publication Editor & Publisher, wrote about an “all-steel robot reporter, equipped with a sensitized recording tape, and to be used by the British Broadcasting Corporation to cover political meetings, sports and public dinners” as a harbinger of further automation.

Pew quoted E.I. Collins of the Jersey City (NJ) Journal, who wrote a bit of newsroom poetry to mark the occasion:

“Yes, the robots have taken our places,

And we’re through with the newspaper game –

We’ve taken a spot on the sidelines,

No longer the ‘shadows’ of Fame.

When the President issues a statement

Or the long shot clicks in the game,

A robot ticks off the story —

But somehow it isn’t the same.”

That was in 1934, which goes to show that news workers have been worried about the ways technology would impact their jobs for nearly a century. In fact, apprehension around the introduction of machines that could set type, and later, software that could perform other tasks traditionally done by hand, such as layout, date back to at least the 1920s and 1930s, if not before.

In 1952, during the era of early, massive mainframes, Robert Brown, also of Editor & Publisher, joked about how “it won’t be long before we will have a completely automatic newspaper — one that puts itself out without manpower of any kind.” He pointed out that since the 1930s, automation in the form of the teletypesetter (which sent wire stories to newsrooms) and “pneumatic types and automatic coffee and soft drink dispensers” had already taken away newsroom jobs.

“We’ve already eliminated most of the time-honored workers in the newspaper vineyard… All we need are one or two more automatic devices,” Brown wrote (probably) tongue-in-cheek.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the introduction of computers for basic layout and production tasks presaged the widespread use of word-processing software. These tasks, done via shared computer terminals (and often used by as many as four or more reporters), introduced a new reliance on spell checkers and content management systems that meant that news workers — and more indirectly, their audiences — were getting their news from at least partially automated systems, as Juliette De Maeyer, an expert on the early computerization of the newsroom, has noted.

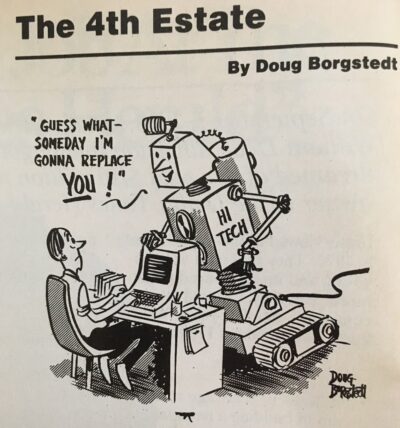

By the 1980s, most reporters had desktops of their own, and not just “dumb” terminals, as had been common in the 1970s. They were expected to use company intranet and message boards, early digital filing and story-archive storage systems, and the aforementioned CMS tools to get their stories written and revised. Even before the internet and more sophisticated AI tools, reporters were already worried about their jobs, as this cartoon by Doug Borgstedt in Editor & Publisher from September 1986 shows.

In the 1990s, the early commercial internet and use of browsers as the go-to places to check facts and find stories spawned a number of anxious think pieces in journalism trade publications. As search engines seemed to replace old-school gumshoe reporting (though in reality this was not often the case), reporters and editors alike worried about the impact on readers, too.

Marilyn Greenwald, a reporter who covered the technology industry, noted in 2004 that the internet — and the automated systems that came with it — meant that readers might not be getting verified facts. Or, at least, that they might enjoy less solid reporting than those from a pre-internet era. The internet provided “such readily available sources [that] are seductive because they can hide the fact that good reporting almost always requires some sweat,” she wrote. “Reporters, editors and news directors have little time to work on longer enterprise stories that cannot be done by one person in one or two days. If information is not readily available on their computer screens, many student and professional reporters simply are not encouraged to seek it out.”

Recent Technology Anxiety in the Newsroom

Since the 2000s, technology and AI have gradually found their way into both how news workers do journalism and how people consume the news.

Automated social-media posting in the late 2000s with Facebook and Twitter, and the use of algorithmic selection of stories, while common today, was less clear, with a mixture of human and machine decisions that were hard to tease out.

The curation of breaking news, for example, from even a mainstream outlet such as NBC News, was done by both software and humans. While this is not quite the same as an LLM writing stories or generating other kinds of narrative “content,” scholars such as C.W. Anderson and Arjen van Dalen predicted that news organizations would increasingly rely on AI not just for sharing of stories, but eventually also their production.

In 2014, the Associated Press began automating financial stories. In 2016, The Washington Post used an early AI tool to create stories about the Olympics and that year’s election. While computers had helped with coverage of elections since the 1950s, this was different. The rest of the 2010s was marked by similar, fairly quiet experimentation, before the issue burst into the public’s consciousness (or at least the consciousness of journalists) in 2023 and especially this year, in the wake of the pandemic.

So why does it matter that machine-generated content has a long history? Or that we, as news consumers, know that AI tools have been in use for at least a decade?

As a media historian who studies long, messy technological transitions, I think that it’s important that people who rely on both human-crafted and curated news, along with the AI kind, expect — and even demand — transparency and the ethical use of AI.

For the sake of accountability, it’s important to know who — or what — writes about our institutions and culture. And for the sake of media literacy, it’s also vital for readers to know how to read the news, and how to verify facts, on their end. Both of these functions get far more difficult when it’s unclear if a machine, or a person, or some combination thereof, is at work.

A good example of a news organization responding to these kinds of concerns is The Guardian, which has set out its internal and external guidance on the use of AI in its newsroom. Other outlets have been less forthright, such as Sports Illustrated, which hired a company that used AI to generate fake bylines, or have had to correct numerous errors generated by AI tools, as with CNET, which was forced to issue updates for 41 of 77 AI-generated stories.

The use of machines in the gathering, editing, and publication of news is nothing new.

But what is new is the degree to which machines themselves are making judgment calls regarding the value of news. That’s why we should be smart news consumers who reward those outlets that practice the ethical use of AI, and, to borrow from the 1930s-era newsroom poem above: still demand that to “get the real punch in the story, A [human] reporter will cover the news!”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now