April 3, 2024, marks the centennial of iconic actor Marlon Brando, whom the American Film Institute ranked among the top five greatest movie stars of the 20th century. But according to Burt Kearns, author of Marlon Brando: Hollywood Rebel, Brando’s influence is still keenly felt today.

Kearns is usually drawn to cultural figures who fly under the radar (his last book was Lawrence Tierney: Hollywood’s Real Life Tough Guy). That’s not Brando, about whom much has been written. But Kearns is also drawn to cultural outliers, and Brando profoundly changed the art of acting (even if he was dismissive in interviews about his own profession).

The challenge, Kearns told The Saturday Evening Post, was to find a fresh angle on this much chronicled artist enshrined in myth and legend. Marlon Brando: Hollywood Rebel is not another biography, but more an examination of Brando’s enduring influence 100 years after his birth and 20 years after his death.

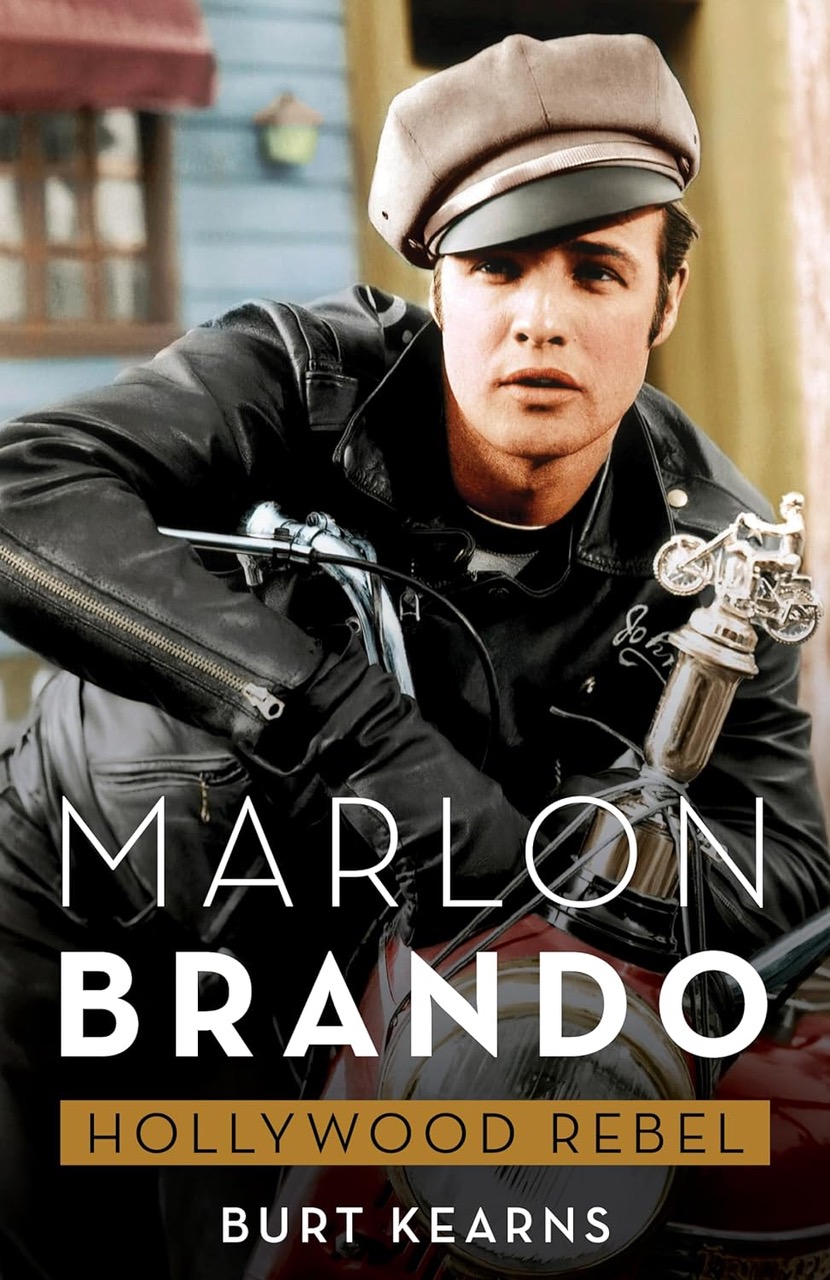

A starting point is one of Brando’s most iconic roles, that of motorcycle gang leader Johnny Strabler in The Wild One (1953). “This was a film that inspired a youth revolution,” Kearns says in a phone interview. “There were no biker flicks at the time. There wasn’t a youth market. Brando wanted to make movies that addressed issues that were plaguing America and society at the beginning of the 1950s, anything from returning World War II veterans and their trauma at not being able to fit it in to society (The Men) to juvenile delinquency.”

Donald Liebenson: What was your personal connection to Marlon Brando?

Burt Kearns: I grew up in the 1960s. Brando was part of the zeitgeist, part of popular culture. But that decade was Brando’s dead zone, according to a lot of people, when it came to film. I was more likely to remember Herman Munster as Hot Rod Herman on The Munsters, or Jethro Bodine dressing up like Brando on The Beverly Hillbillies in the episode “The Clampetts Go Hollywood.” I had the poster of Peter Fonda as Captain America in Easy Rider. I was 16 in 1972 when The Godfather came out. Later that year, Last Tango came out. And that was all about, “Oh boy, sex and nudity, I gotta see that.” Watching it 50 years later, I was devastated by the scene with Brando in the hotel room talking to his dead wife, a scene he improvised.

Scene from Last Tango in Paris (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

DL: You write extensively in the book about The Wild One, and there’s that famous scene where someone asks Johnny what he’s rebelling against, and Johnny responds, “Whataya got?” Brando is the poster child for Method acting. What was the Method a rebellion against?

Scene from The Wild One (Uploaded to YouTube by Marie Ruggirello)

BK: People compare Brando and acting to Bob Dylan and pop music. Before Dylan, you could be a singer and sing someone else’s songs. After Dylan came along, you’re bringing yourself to your music whether you’re Lennon and McCartney or Paul Simon or Joni Mitchell. Brando did the same kind of thing for film acting. People used to make fun of Brando or say he was too lazy to learn his lines because he used cue cards or wore an earpiece. That was a deliberate thing on his part to remain in the moment. People in real life don’t just come up with a pithy line. In the “I coulda been a contender” scene with Rod Steiger in On the Waterfront, he’s got lines on the roof of that cab, and you see him looking up so he can find that response.

Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips

DL: If someone wants to have a Brando 100th birthday binge, what five films would you recommend? Let’s leave out The Godfather because everyone knows that one.

BK: I’ll offer six. I’d start with The Wild One, which launched a youth, rock, civil rights, and fashion revolution.

On the Waterfront is the peak of his Method acting. There are scenes where he doesn’t even seem to be acting, it’s just life.

With Bedtime Story (a rare comedy in the Brando canon), we move forward into the middle of what is known as his lost decade, the ’60s, but which really has some of his greatest work. Bedtime Story was co-written by Paul Henning, who co-created Green Acres, so how can you go wrong with that? It inspired Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, and that film’s director, Frank Oz, later directed The Score with Edward Norton, Robert DeNiro, and Marlon Brando. Brando tortured Frank Oz. He called him Miss Piggy (a reference to his signature Muppet Show character). Oz had to leave the set and let Robert DeNiro direct for him. And I think it’s because of Dirty Rotten Scoundrels.

Next, Reflections in a Golden Eye, directed by John Huston. This is where Brando plays a repressed and closeted homosexual Army major married to Elizabeth Taylor. He’s tremendous in it.

I recommend Burn! from the director of The Battle of Algiers [Gillo Pontecorvo]. Brando portrays a character hired by the British government to stoke a revolution in the Caribbean on behalf of the sugar industry. Brando considered this to be his greatest acting. An alternate version, Queimada, is available on YouTube and is a better cut of the film.

And Last Tango in Paris. He had a director who couldn’t really speak English and who encouraged him to go out there and ad lib and create this character. Brando gave so much of himself that he said he would never again put himself out there on film like that, and he never did.

I do have six honorable mentions: The Men, his first film, A Streetcar Named Desire, Sayonara, Mutiny on the Bounty, The Nightcomers, and The Island of Dr. Moreau, which is insane, but without it, there never would have been a Mini-Me (in the Austin Powers films).

DL: You have a sweet shout-out in your book to comedian Gilbert Gottfried, who took great comic liberties with the claims about a sexual relationship between Brando and Richard Pryor. On his podcast, he once mentioned talking to a college student who said they didn’t know who David Letterman was. Do you think this new generation is aware of Brando?

BK: Young people today have so much more information at their disposal than we did. But they seem to have little sense of history. History to them seems to begin with this century. The thing that turns me on is seeing the roots of things: to know that Elvis didn’t want to be a singer; he wanted to be Marlon Brando. There’s a scene in Priscilla where they go to watch On the Waterfront and he says, “That’s what I want to be.”

I came up in the punk rock scene in New York. I was involved with the guys who started Punk magazine. The very first issue was dedicated to Brando, who they called the original punk. That’s what I would like readers to come away with.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Another great feature, Donald. Marlon’s one of my favorite actors from Hollywood’s Golden Age. Ironically. I just saw ‘The Wild One’ for the first time, just last month. It seemed like it would/should have been from a later section of the 50’s. It may have helped pave the way for ‘Rebel Without A Cause’ and Elvis, but I’m not sure.

A film I saw 2 years ago was ‘Lady In A Cage’ starring Olivia de Havilland and Ann Sothern. It also included an early film appearance by James Caan whose role and acting method certainly seemed to have been inspired by Brando. Ann’s role may have paved the way for Elizabeth Taylor having the guts to let herself go (too) some years later in ‘Virginia Woolf’.

The opening credits in ‘Lady In A Cage’ looked like they were inspired by the “new” graphics of The Saturday Evening Post starting in late 1961, but I’m not sure of that either. I am though, of Marlon Brando being one of the screen’s MOST electrifying mid-century actors and film stars.