This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

At a December rally in New Hampshire, former President and current 2024 GOP frontrunner Donald Trump said of immigrants who are “coming into our country from Africa, from Asia, from all over the world” that they are “poisoning the blood of our country…That’s what they’re doing. They’re destroying our country.” Later that night on a post on his Truth Social website he reiterated his belief that “illegal immigration is poisoning the blood of our nation. They’re coming from prisons, from mental institutions—from all over the world.”

As many commentators have noted, Trump’s use of “blood poisoning” echoes a foundational concept in Adolf Hitler’s racist manifesto Mein Kampf (1925). Yet we need not look to Nazi Germany to find examples of such rhetoric in the 1920s, as the Immigration Act of 1924 likewise explicitly supported exclusionary views of both immigrants and American identity. The 100th anniversary of that law also offers us an opportunity to remember two other 1924 documents, inspiring texts that model an alternative, inclusive vision of America.

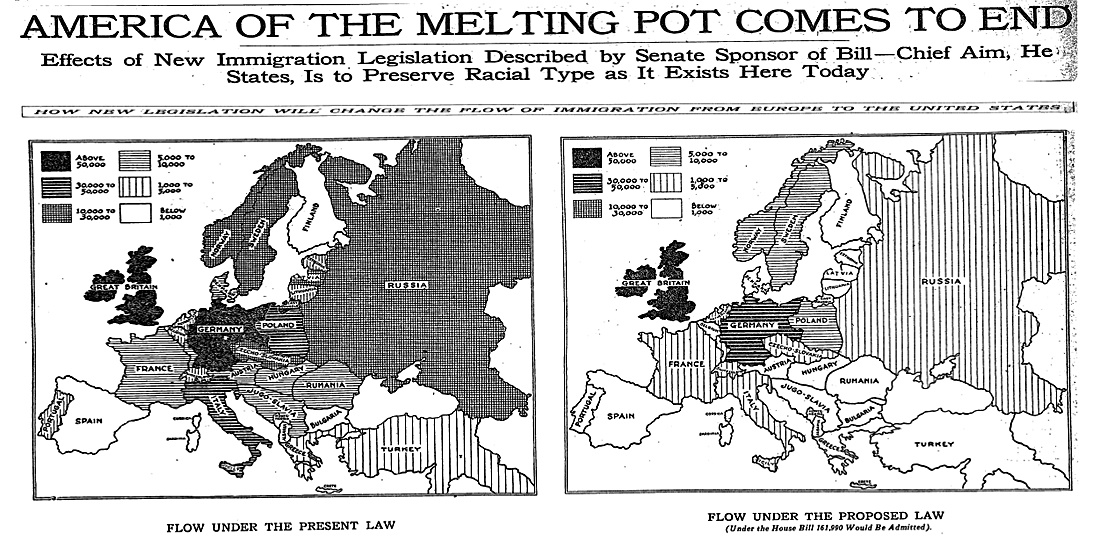

Also known as the Johnson-Reed Act, the Immigration Act of 1924 extended and made permanent the discriminatory quota system that had been temporarily established by the 1921 Emergency Quota Act. Overtly recognized by the State Department as an effort “to preserve the ideal of U.S. homogeneity,” the law’s annual quotas used formulas based on 19th century census data to severely limit the number of immigrants who could arrive from Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, and Africa, with many nations such as Albania, Egypt, Greece, South Africa, and Turkey allowed only 100 legal immigrants per year (in overt and striking contrast to numbers such as Great Britain’s 65,721, Germany’s 25,957, and Ireland’s 17,853).

When it came to immigrants from Asia, the 1924 law was even more exclusionary. Building on prior laws including the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and the Immigration Act of 1917 (which had created the so-called Asiatic Barred Zone), the 1924 law included a provision called the Asian Exclusion Act, which extended such restrictions to immigrants from every Asian nation except the Philippines, which was under U.S. control. The law also made it illegal to admit any immigrant who was not eligible to become a U.S. citizen (a provision that explicitly restricted all Japanese arrivals, for example), reinforcing this exclusionary vision of American citizenship and identity.

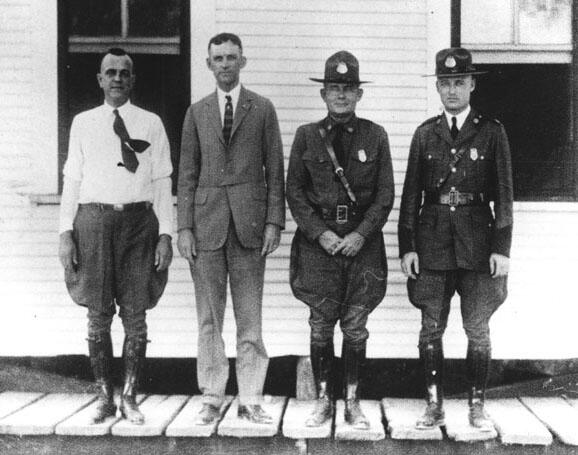

The 1924 law didn’t simply enact such exclusionary policies, however; it also created a system through which they could be more consistently and violently enforced. Although mounted armed men had been riding along the U.S.-Mexico border since the early 20th century, ostensibly looking for Chinese arrivals attempting to circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act, it was the Immigration Act of 1924 that formally authorized the creation of a United States Border Patrol. Established just two days after the act’s passage, this new national entity would serve as a means not simply of enforcing quotas and other immigration restrictions, but also of policing arrivals in a variety of other ways, such as imposing an exorbitant $8 head tax and $10 visa fee for all Mexican immigrants (despite the 1924 law having left Western Hemisphere nations outside of its purview).

The views behind these various 1924 policies were expressed clearly in a speech on the Senate floor by one of the law’s chief supporters. Speaking on April 9th, 1924, South Carolina Senator Ellison DuRant Smith argued that “it seems to me the point as to this measure…is that the time has arrived when we should shut the door.” And Smith made clear that such exclusionary immigration restrictions were directly linked to a white supremacist definition of American identity, adding, “Thank God we have in America perhaps the largest percentage of any country in the world of the pure, unadulterated Anglo-Saxon stock…It is for the preservation of that splendid stock that has characterized us that I would make this not an asylum for the oppressed of all countries, but a country to assimilate and perfect that splendid type of manhood that has made America the foremost Nation in her progress and in her power.”

This exclusionary vision of America was widely shared by those in power, as the Immigration Act of 1924 passed the House 308-62 and the Senate 69-9. Of course, it wasn’t the only federal law passed in 1924; another law passed that same year embodied a far more inclusive view of American citizenship and community. As I highlighted in this Considering History column, the groundbreaking and hugely important 1924 Indian Citizenship Act extended American citizenship to “all Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States,” reversing centuries of exclusion and extending fundamental civil rights such as the right to vote to Native Americans. Commemorating this important law on its 100th anniversary also allows us to celebrate the many Native American activists and allies who fought for its passage, from author and musician Zitkala-Ša and performer and lecturer Nipo T. Strongheart to the white clergyman Joseph K. Dixon, who highlighted Native American military service in WWI and asked, “Now, shall we not redeem ourselves by redeeming all the tribes?”

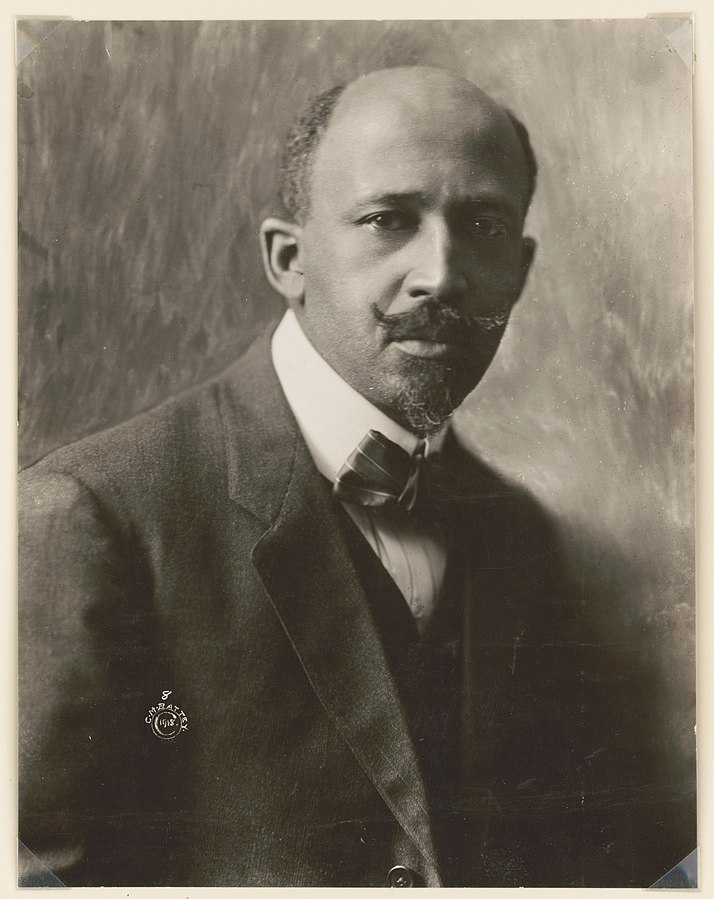

Offering an even more direct challenge to Senator Smith’s white supremacist vision of American identity was a 1924 text by one of our most inspiring figures: W.E.B. Du Bois’ book, The Gift of Black Folk: The Negroes in the Making of America. Du Bois begins by acknowledging that “it is not uncommon for casual thinkers to assume that the United States of America is practically a continuation of English nationality,” but argues that “it is high time that this course of our thinking should be changed. America is conglomerate…It represents peculiarly a coming together of the peoples of the world.” While Du Bois focuses on the contributions of African Americans in particular to American history, his main argument is an even more overarching and inclusive view of the nation itself. As the battle between exclusion and inclusion ramps up once again in 2024 America, we can learn much from the exclusive and inclusive laws and texts from 100 years ago.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I find it peculiar that the Post doesn’t mention the limits of what Rockwell could paint. There is no mention that the Post didn’t allow Blacks to be included in his paintings unless in a subservient position. I believe it only fair to include the above in his biography included in this newsletter. History should not be erased.