A stop at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum is like paying a visit to old friends. Hanging on the museum walls are huge framed cartoons of Lucy tormenting Charlie Brown, Beetle Bailey working his way under Sarge’s skin, and Hobbes crouching under Calvin’s school desk, whispering that the sum of 7 + 3 is 73.

In adjacent display cases, you’ll also find a Steve Canyon lunchbox, a Little Orphan Annie board game and decoder ring, and B. Kliban cat hats. Pull out some drawers beneath them to find copies of Mad magazine, a Captain Marvel comic book, and a cartoon correspondence course complete with a “Gag Master Wheel.” In yet another case, editorial cartoons of the 19th-century master Thomas Nast show how he created the elephant as the symbol of the Republican Party.

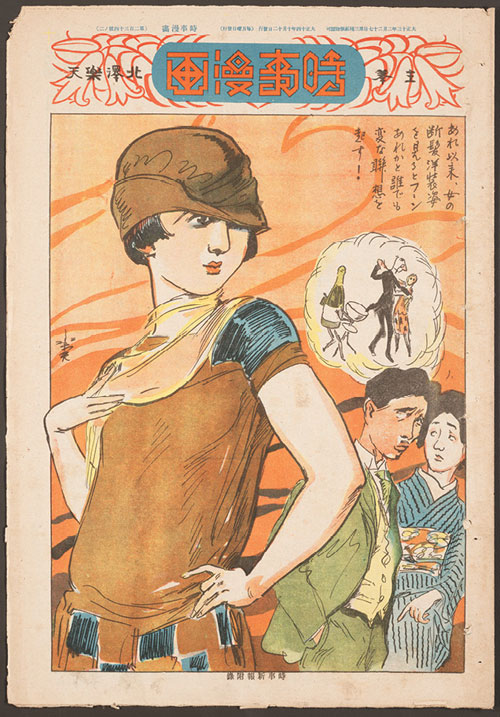

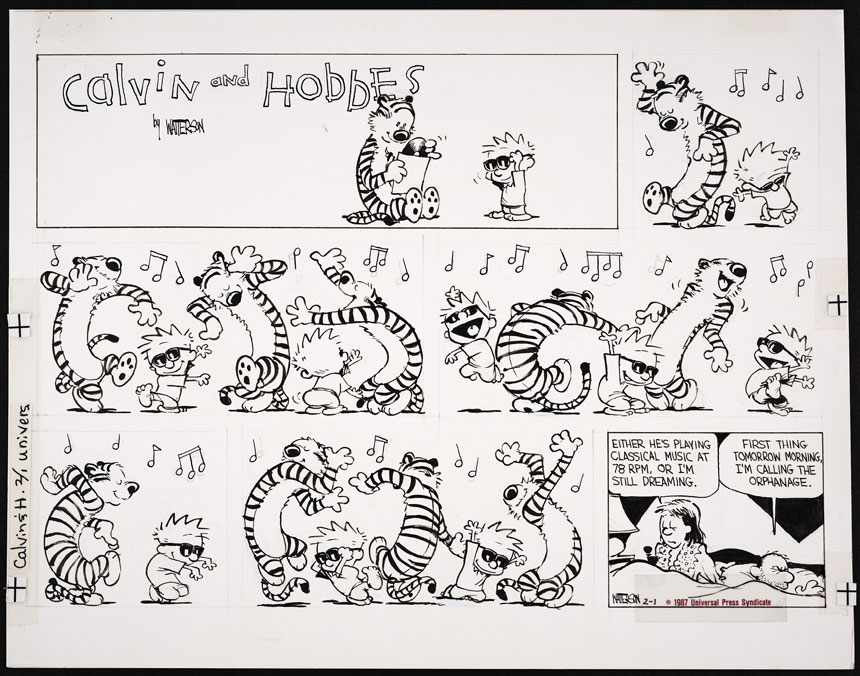

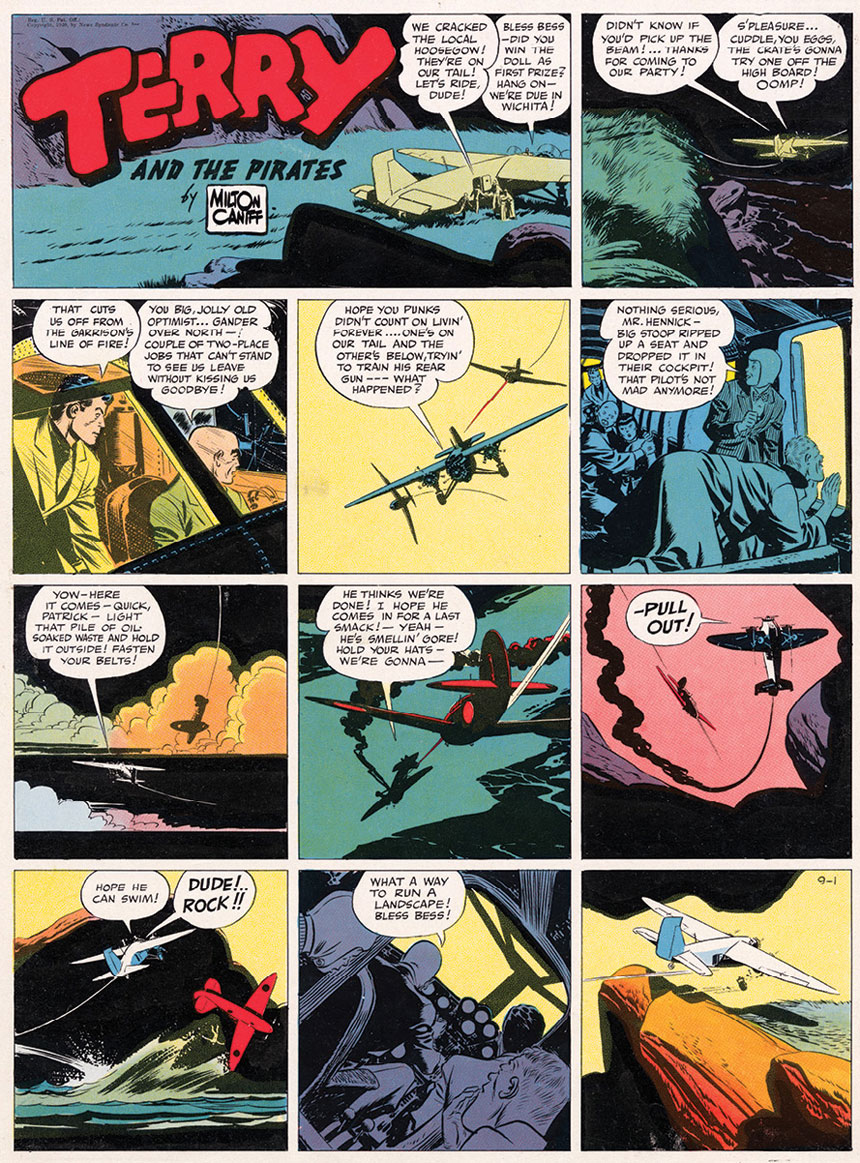

There’s no telling what treasures you’ll uncover at this unique institution located on the campus of The Ohio State University in Columbus. Quite simply, it’s the largest repository of cartoon art in the world, with 300,000 original cartoons, 45,000 books, 67,000 serials and comic books, and a whopping 2.5 million comic strip clippings. Name any cartoonist, even ones that aren’t widely known, and the vast collection will almost surely have representative samples of their artwork. And in some cases, BICLM has the entirety of the artist’s work, including the collections of Milton Caniff (Steve Canyon and Terry and the Pirates), Walt Kelly (Pogo), and Bill Watterson (Calvin and Hobbes). Huge holdings of underground comic books and even Japanese manga are also among BICLM’s treasures.

Named for a beloved local cartoonist at the Columbus Dispatch, BICLM begins with the assumption that cartoons are an art form worthy of serious study. And in fact, scholars from all over the world beat a path to Columbus to browse the collections as they work on books or dissertations. Caitlin McGurk, curator of comics and cartoon art at BICLM and an associate professor at Ohio State, has seen researchers dig deep looking for trends in humor over the decades or to find how women have been treated in the comics or how fashion has changed over time.

“The comic format can convey stories and meanings that transcend language, using images to convey universal messages. Plus, many comics are just plain beautiful art,” McGurk says. And for those who label comics as merely expressions of pop culture, McGurk replies, “Pop culture almost always reflects trends going on in the greater society. So cartoons are a reflection not just of the artist’s thoughts and ideas but also of the society they live in. There’s a world of valuable information we can obtain by studying cartoon art.”

McGurk says scholars who have visited recently have looked at how race has been visually depicted over the decades and at how music was represented in early comics. But not long ago, she also saw a father introducing his young son to the enormously popular Calvin and Hobbes, which ended its 10-year-run in syndication in 1995.

That’s because scholars aren’t the only ones who can request to see the vast materials owned by BICLM. Anyone, even those with a casual interest, can stop by BICLM’s reading room and ask for samples of anything in the library’s cavernous archives. Visitors use an online database to fill out a request and then have it brought out for their perusal. The materials can’t leave the room, and you may be requested to wear gloves, but if you have an urge to see treasured comics of your childhood — everything from Spider-Man to the Legion of Super Heroes — BICLM is happy to indulge your journey down Memory Lane.

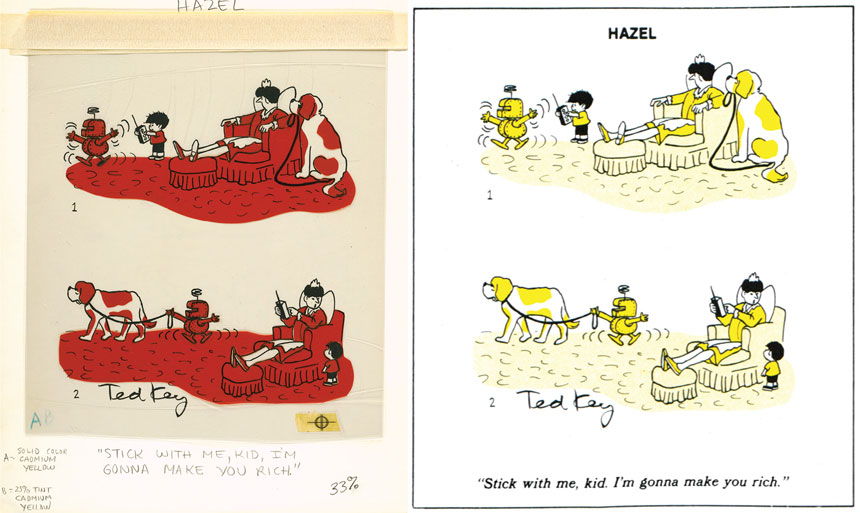

In many cases, it will be the cartoonist’s actual artwork that you can examine, as opposed to a comic book or photo-copy of the original art. Ask to see the artwork of Ted Key, creator of the cartoon strip Hazel, about a bossy household maid, which ran in The Saturday Evening Post for many years; you can examine eight different drawings done by Key of the irrepressible maid that have been marked up by the editor in preparation for publication, complete with tinted plastic overlays. Key also wrote a two-page letter to the curator at BICLM discussing what he hopes students of cartooning can learn from his artwork. There’s even more to be seen of the work of Brad Anderson, creator of Marmaduke, a cartoon about a lovable Great Dane. Anderson’s family donated his complete collection to BICLM after his death in 2015, making it possible to watch the evolution of Marmaduke as his original scowl was transformed into a smile.

In addition to selections from its permanent collection on rotating display in the museum, two other sizable galleries are devoted to temporary themed exhibits. Two recent exhibits included “Art of the News: Comics Journalism” and “Man Saves Comics!,” which tells the amazing story of San Francisco cartoon historian Bill Blackbeard, who in 1967 started collecting hundreds of thousands of original cartoon strips when libraries started microfilming them and discarding the originals. He donated his collection to BICLM in 1998; it arrived in Columbus in six semi trailers filled with 75 tons of material.

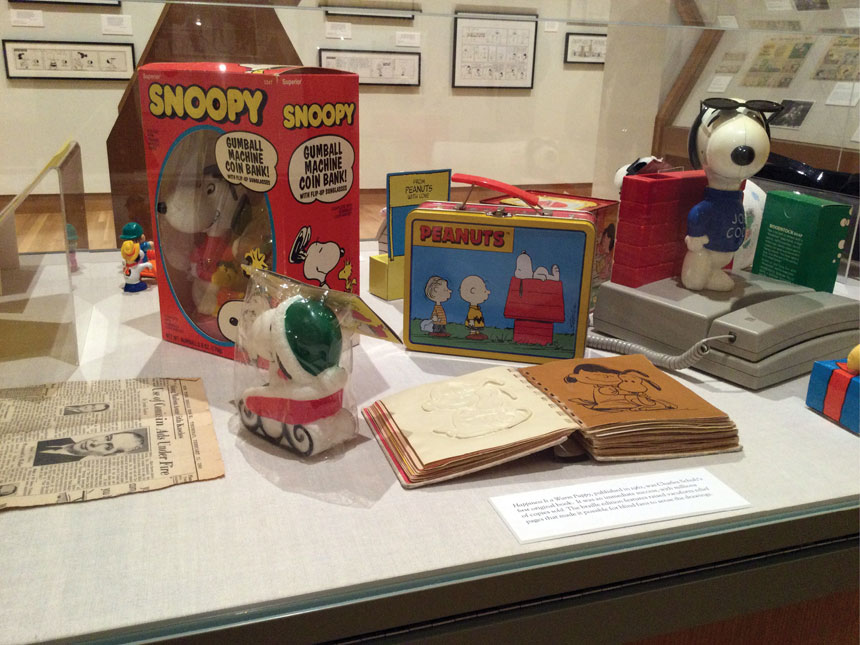

Other past exhibits have included salutes to Charles Schulz, creator of Peanuts, on the centennial of his birth, as well as thematic explorations on subjects like the environment, women’s innovations, and even “Two Centuries of Canine Cartoons.”

Running until November 19, 2023, a rare two-gallery exhibition is devoted to the work of popular graphic novelist Raina Telgemeier, whose novels Smile, Sisters, and Guts have appeared on New York Times bestseller lists. McGurk expects a massive attendance at this retrospective. “People will plan family vacations around it,” she predicts.

BICLM had its beginnings in 1977 when Ohio State alumnus Milton Caniff donated his entire work to his alma mater, including decades of his drawings of Steve Canyon and Terry and the Pirates. Lucy Shelton Caswell was given a six-month appointment by the School of Journalism to organize this vast collection. “Long story short — I stayed a lot longer than six months,” says Caswell, who eventually became curator of the cartoon library, dedicating herself to adding more content beyond Caniff’s donation.

Other cartoonists, like Pogo’s Walt Kelly, started donating their own work, and professional organizations like the National Cartoonists Society contributed their entire archives. Soon, even larger entities started donating their holdings; BICLM absorbed the collection of the International Museum of Cartoon Art, founded by Mort Walker, creator of Beetle Bailey and Hi and Lois. Then Caswell landed the biggest donation of all: Blackbeard’s gargantuan San Francisco Academy of Cartoon Arts (including those six trailers full of cartoon clippings). “To say our growth was exponential is putting it mildly,” Caswell says.

In the beginning years, Caswell sometimes heard detractors decrying the value of cartoon art. She paid them no mind. She knew that just by itself the original donation by Milton Caniff was enormously important. “Caniff was a giant,” she says. “He appeared on the covers of Time and Newsweek, and the strong narratives he created in his comics, not to mention their sheer artistic quality, made his work enormously influential. So I never felt a need to defend the value of cartoon art. To me, it was obvious there was no question it was a field that merited serious study.”

Ohio State offered a substantial boost to BICLM in 2014 when it made available a recently renovated 30,000-square-foot space inside Sullivant Hall, allowing substantially more room than in its previously cramped and hard-to-find location. What’s more, BICLM now is in close proximity to the university’s dance and music departments; the Wexner Center, a cutting-edge contemporary arts venue; and the huge Mershon Auditorium, site of numerous concerts and lectures, making BICLM part of a mecca for the arts on the OSU campus.

Caswell retired at the end of 2010, replaced by Jenny Robb as head curator. Caswell has remained active in the field, however, writing books — including one on Billy Ireland — and guest curating special exhibitions at BICLM, including one on the Civil War in cartoons. She was also the curator for the highly popular show on Peanuts creator Charles Schulz, which closed in 2022.

In her search for materials to include in the exhibits, Caswell tries to find surprising, little-known facts on the subject matter. In the exhibit on Schulz, for example, she focused on the man as a person, one whose friends called him “Sparky.” “Not many people know he was a very serious hockey player,” she says. “In fact, he skated on the day he died.”

And of course Caswell’s legacy lives on in the form of the largest collection of cartoon art in the world. Other places, such as Columbia and Syracuse universities, have comics collections, but no other institution has the breadth and scope of the one Caswell was instrumental in putting together during her 33-year tenure. As Caitlin McGurk put it: “This is the house that Lucy built.”

Caswell is also a vice president and one of three founders of Cartoon Crossroads Columbus, commonly referred to as CXC, a four-day annual comics, art, and animation festival usually held in late September. (Visit cartooncrossroadscolumbus.org for more information.) The city-wide festival takes place not only at BICLM but also at the Columbus Metropolitan Library, Columbus College of Art and Design, and the Columbus Museum of Art. The more than 40 hours of programming includes panel discussions, artist spotlights, and an expo of more than 100 artists displaying and talking about their work, as well as networking and social events. Hundreds of cartoonists and fans come from all over the nation, with thousands more attending virtually.

Past cartoonists and keynote speakers read like a Who’s Who of the cartoon industry, including Garry Trudeau, creator of Doonesbury; Jules Feiffer, for decades a cartoonist with The Village Voice; and Art Spiegelman, creator of the graphic novel Maus. Dozens of other emerging artists have also contributed their talents to the festival.

“CXC is all about building bridges, not only among the cartoonists themselves but also with people who love cartoons who get to meet the creators and learn about the process by which they create their art,” says Jay Kalagayan, executive director of CXC. “People who are thinking of joining the industry are also part of the mix. Put all those people together in one place and they share ideas, they network, and they potentially form friendships for future collaborations. It doesn’t get much better than that.”

Another rare opportunity at CXC is to take a tour through the labyrinthine stacks and storage area at BICLM, which is seldom opened to the public for security reasons. In addition to seeing some rarely viewed cartoon art, you’ll marvel at how the bookshelves squeeze together like an accordion, saving substantial space and keeping most of the artwork out of sight.

Another option is to watch a highly entertaining video on the BICLM website; it not only takes a walk through the stacks but also reveals gems such as an early Charles Schulz cartoon preceding Peanuts. The video also has cartoonists like Garry Trudeau discussing their work. Curators Jenny Robb and Caitlin McGurk also talk about little-known items in the archives, such as letters written to Lynn Johnston, creator of the comic strip For Better or For Worse, when Farley, the family dog, passed away; or another “spicy” letter written by novelist John Steinbeck to Milton Caniff, discussing his feelings for the Dragon Lady in Terry and the Pirates. In the background of this video you may even spot the cartoon character Nancy (actually a man in costume) working in the stacks.

exhibit Celebrating Sparky: Charles M. Schulz and Peanuts. (Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at The Ohio State University)

But of course you can see actual cartoon art either in BICLM’s reading room or in the galleries where signage beside the cartoons offers ample opportunity to learn more about the exhibit. You’ll read how Bill Watterson originally depicted Calvin with his hair covering his eyes, which Watterson quickly changed to Calvin’s signature spiky haircut. You’ll also discover how it was 19th-century political cartoonist Thomas Nast who created our modern depictions of Santa Claus. Even though you may well laugh when you examine something at the world’s largest cartoon library, make no mistake that the fans, scholars, and researchers who visit the library consider it very serious business.

Rich Warren is a freelance journalist whose work has appeared in National Geographic Traveler, AAA World, AAA Explorer, Fodors.com, AARP, and more. To find out more about the BICLM online, visit library.osu.edu/biclm.

This article is featured in the November/December 2023 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Looks like it would be a great place to visit sometime.

Small world. I recently moved to Wisconsin, close to where my grandfather’s brother Clare Briggs was born (Reedsburg) and where my mother and I watched the dedication of the historical marker in 1978. I drove up there in June of this year and was happy to see the improvements. Clare is considered one of the first or earliest comic strip artists. (Oh, Skinnay, A Piker Clerk) Early this year, because I knew I was moving, I shipped a few boxes of my research and some of his original artwork to this museum. I followed the ever-changing address of the museum from New York to Boca Raton, FL to CA to OH. I am happy to say I believe the school is the perfect choice for the placement of this collection. (A librarian’s opinion.) I have several cousins who graduated from this school and live nearby. I am in contact with some of Clare’s descendants. Thank you for writing this article.

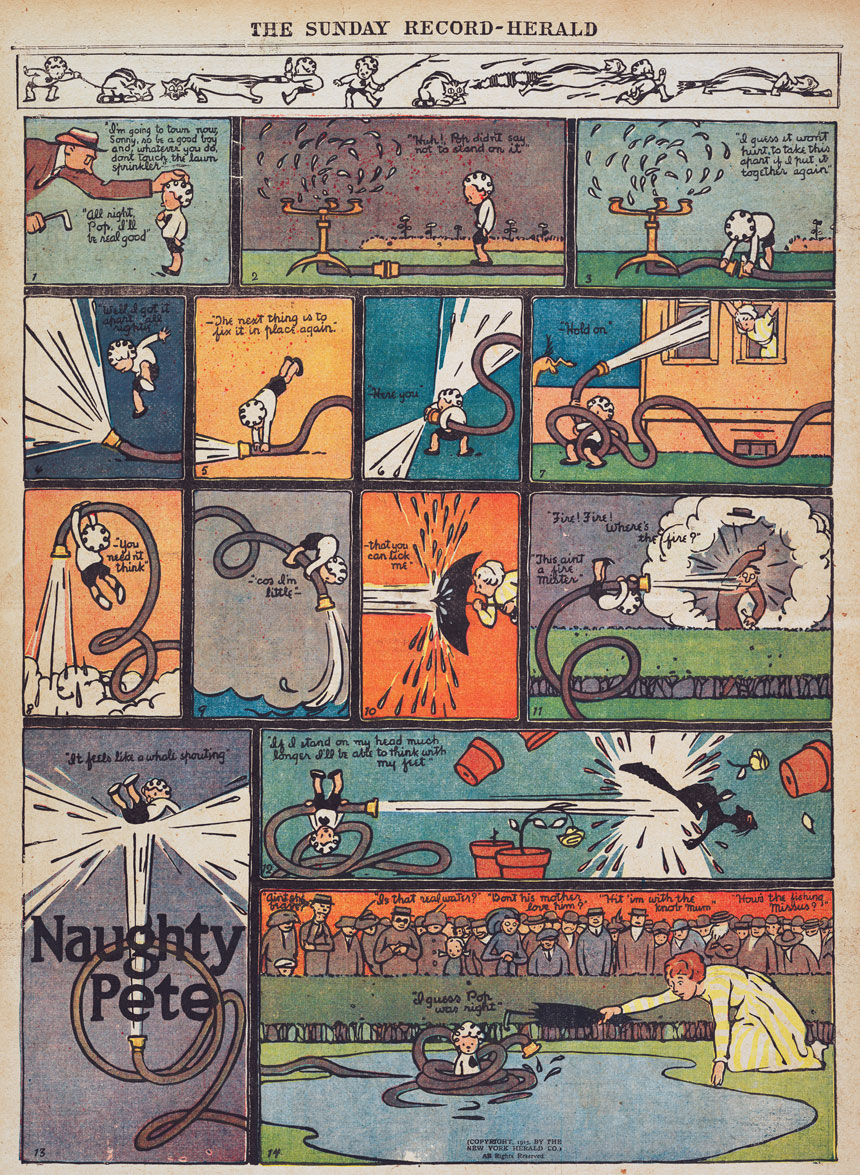

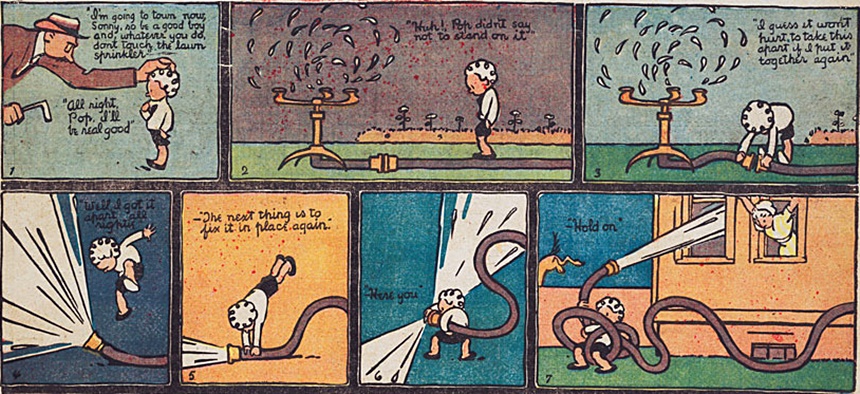

This is an informative article. I never heard of “Naughty Pete” before. I now need to see the other 17 installments!