This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

The confluence of Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month and Memorial Day offers us an opportunity to commemorate the many Asian Americans who have served with courage and distinction in the U.S. Armed Forces. A couple years back I dedicated a column to one such community, Hawaii’s Varsity Victory Volunteers (VVV), Japanese American college students who after Pearl Harbor pushed for the opportunity to serve both the territory and the nation. When the U.S. War Department reversed its official policy and allowed Japanese Americans to enlist, thanks in no small measure to the VVV’s influence, most of those young men became part of the 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team, an all-Japanese American regiment that would by the war’s end become the most decorated military unit in American history, exemplifying the best of American active patriotism.

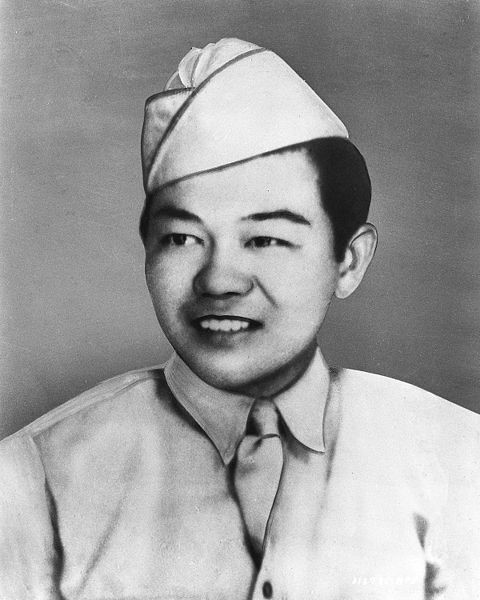

The 442nd’s more than 14,000 awards included numerous Purple Hearts, Bronze and Silver Stars, and Distinguished Service Crosses among many others. But for Memorial Day, a holiday that honors those who have given their lives while serving in the armed forces, it’s particularly apt to remember the regiment’s posthumous Medal of Honor recipient, Sadao Munemori. And he’s just one of many fallen Asian American servicemen to receive the Medal of Honor posthumously.

Munemori (1922-1945) was born in Los Angeles to Japanese immigrant parents, Kametaro and Nawa Munemori, and became an auto mechanic after graduating from Abraham Lincoln Senior High School in 1940. Even though he had already volunteered for the U.S. Army in November 1941, a month before Pearl Harbor, his parents and siblings were among the hundreds of thousands of Japanese Americans incarcerated in the internment camps (they were taken to Manzanar). But Munemori continued to serve, waiting out the change in policy and volunteering for the 442nd as soon as he was able. After completing his combat training, he joined the regiment in Europe, took part in the heroic rescue of the Lost Battalion, and gave his life saving two fellow soldiers during the heavy fighting along Italy’s Gothic Line. For that final act of courageous sacrifice, he was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor in March 1946.

Munemori was the first Japanese American to receive a Medal of Honor, but he was not the only Asian American serviceman to be posthumously honored after World War II. Francis Brown Wai (1917-1944) was the son of Chinese immigrant Kim Wai and native Hawaiian Rosina Wai, and he grew up a talented surfer and athlete on the island. He went on to play four sports at UCLA and planned to work as a banker after graduation, but instead volunteered for the Hawaii National Guard in 1940 (again, well before Pearl Harbor). In an era when few Asian Americans were permitted to hold military leadership roles of any kind, Wai’s training record was so impressive that he was commissioned a second lieutenant in September 1941. He took part in both Operation Reckless, the April 1944 amphibious invasion of New Guinea, and the October 1944 invasion of the Philippines. There, in the brutal battle of Leyte, Wai took charge of a battalion whose officers had all been killed, drew extensive Japanese fire to himself, and allow his comrades to take all of the Japanese positions before he succumbed to his wounds. At the time Wai received a Distinguished Service Cross among other honors, but after a 1990s investigation it was upgraded to a well-deserved Medal of Honor in 2000.

If we extend our timeline to subsequent U.S. military conflicts, we find equally deserving and inspiring Asian/Pacific American posthumous Medal of Honor recipients. One such honoree from the Korean War was Herbert Kailieha Pilila’au (1928-1951), the son of two native Hawaiians who considered conscientiously objecting to the draft due to his Christian faith but chose to serve when drafted in early 1951. His heroic actions during the famous September 1951 battle of Heartbreak Ridge saved the life of his squad leader, Lieutenant Richard Hagar, but cost Pilila’au his own life; when his platoon retook the position, they found forty North Korean casualties around Pilila’au’s body. He became the first native Hawaiian to receive the Medal of Honor when it was awarded posthumously in June 1952.

Two posthumous Asian American Medal honorees from the Vietnam War embody two distinct and equally important sides to U.S. military service in that conflict. Terry Teruo Kawamura (1949-1969) was only 18 when he was drafted into the army in 1968, and was only 19 when he gave his life at Vietnam’s Camp Radcliff, smothering an explosive with his body to protect his fellow soldiers. His posthumous Medal of Honor citation noted the “extraordinary courage and selflessness” of this teenage draftee. Rodney Yano (1943-1969) volunteered for the army in 1961 and served for many years as a helicopter mechanic; it was while performing that role in January 1969 that he volunteered to act as a crew chief for a combat mission in Operation Toan Thang II and sacrificed his life, throwing an enemy grenade off the helicopter. His posthumous Medal of Honor citation highlighted the “indomitable courage” and “conspicuous gallantry” of this mechanic and military lifer.

Finally, I want to conclude by highlighting Vicente Lim (1888-1944), the Filipino American Brigadier General who did not receive a Medal of Honor but who gave his life in World War II, the second war in which he fought with distinction for the United States. Lim was one of many Filipinos who came to the U.S. during the 50-year occupation of the islands, and he challenged and transcended extensive racial prejudice (such as the nickname “Cannibal”) to become the first Filipino American graduate of West Point in 1914.

Like all these posthumous honorees, and like all the Asian/Pacific Americans who have served in our armed forces, Vicente Lim deserves our celebration this Memorial Day and throughout the year.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now