“Is Roosevelt a Menace to Business?”

The question was very much on the minds of Post readers in 1907 as the country headed into a serious recession. The New York Stock Exchange had fallen to almost half of its previous year’s peak. Unemployment had nearly tripled. Many banks had failed and there had been a near record number of bankruptcies.

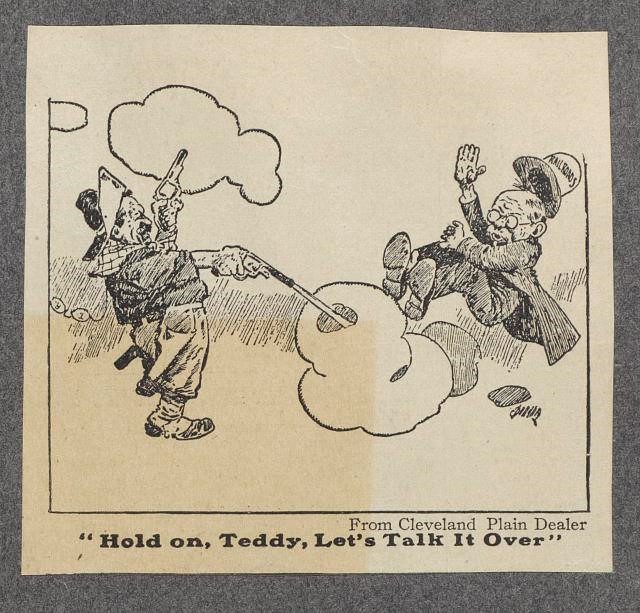

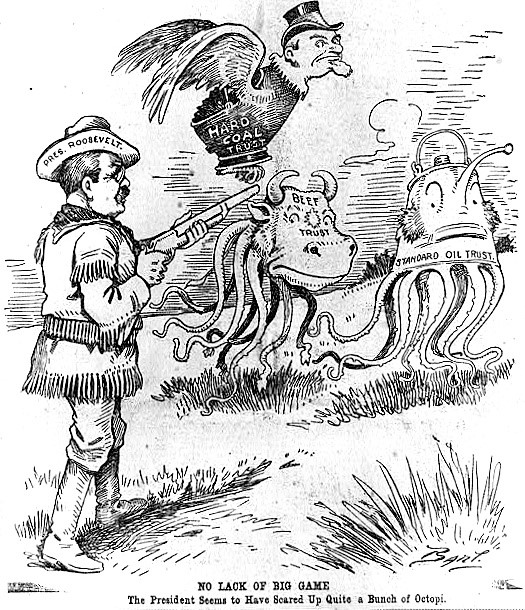

Many businessmen blamed the panic on President Theodore Roosevelt, who believed the public interest was of greater importance than the wealthiest businesses. In his first State of the Union address in 1901, he called on Congress to rein in the country’s powerful monopolies. He subsequently broke up the Standard Oil trust and the Northern Securities Co. railroad conglomerate.

In August of 1907, he promised that his administration would not waver in their prosecution of “malefactors of great wealth” who opposed reform so they could “enjoy unmolested the fruits of their own evil-doing.”

In those days, Post editors greatly admired both the achievements of American businessmen and the progressive reforms of the Roosevelt administration. Now, with Wall Street and Roosevelt in conflict, the Post asked readers to weigh in on how the president was affecting business.

Several of the responses, which began appearing in November, blamed the current recession on Roosevelt.

“Roosevelt has lost no opportunity to denounce what he terms the ‘criminal rich’… This of itself has caused a tremendous shrinkage in values of securities.”

“The President is not a business man. He refused to heed repeated warnings of those competent to advise… He has gone about a vast work with an axe when a scalpel was needed.

“Mr. Roosevelt has talked too much and he has threatened too much. The constant fulminations of Mr. Roosevelt have taught the people to question the honesty of our most upright citizens.”

“[Roosevelt’s] impulsive actions have been the direct cause of the present panic and of the general depression and hard times which will follow.”

“One thing is sure: Roosevelt has created a panic when no panic was due.”

In fact, the panic that threatened Wall Street hadn’t originated with President Roosevelt or from any actions by Congress. It started with Frederick “Fritz” Augustus Heinze, copper magnate and president of the Mercantile National Bank, trying to corner the market in copper.

After partnering with Charles W. Morse, who owned several banks, Heinze bought up shares of copper stocks until he felt he held enough to control the copper market.

But he miscalculated: there were more outstanding copper shares than he’d expected. He hurriedly tried to sell off his copper stocks. In the process, he drove down the price, which affected the Mercantile National, which had invested heavily in copper. Depositors rushed to withdraw their money, and the bank failed. A brokerage house run by Heinze’s brother collapsed, as did the banks owned by Morse.

Depositors and investors everywhere began to wonder how safe their money was. Had their capital been put into other wild speculations, like Heinze’s copper-market bid?

Banks fell like dominos, ultimately arriving at the doors of New York’s Knickerbocker Trust Company and the National Bank of America.

Fortunately, financier J.P. Morgan stepped in to prevent further disaster by making life-saving loans to banks and trust companies. He also intervened to save the value of New York’s city bonds.

The panic subsided, but not before many banks had fallen, businesses had gone bankrupt, and workers had lost their jobs.

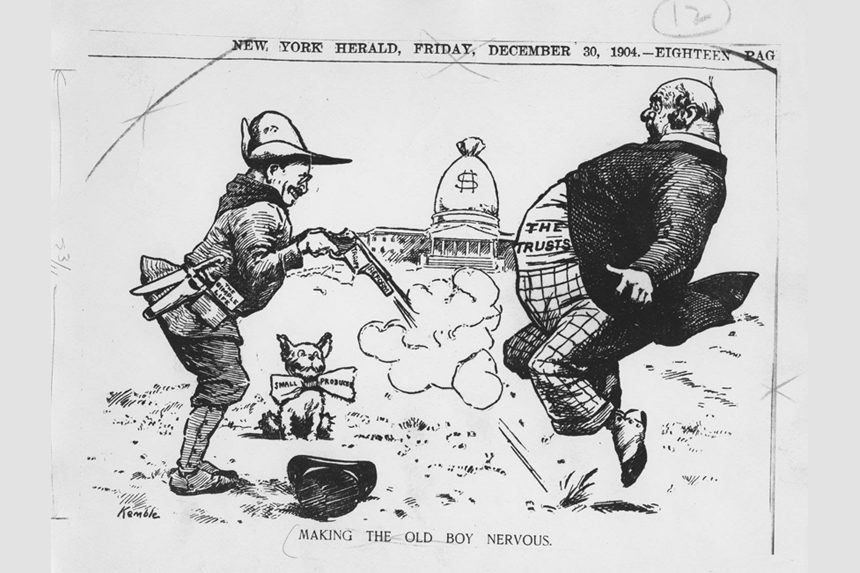

Most of the letters the Post reprinted in its Roosevelt-menace series reflected a new anger against “stock manipulators,” and a general mistrust of Wall Street. For these readers, Roosevelt’s meddling was welcomed.

“If, by the word ‘business,’ The Saturday Evening Post means the continuance of law-breaking, the crushing of weak competitors by big combinations, the use of insurance funds for the private benefit of directors; if it means illegal banking, resulting in loss of confidence in banks all over the country and consequent financial terror —if ‘business’ means these financial methods, then Roosevelt is a wrecker.

“To the small but powerful coterie of financial buccaneers who have been trying to dominate the metropolitan banks and trust companies, and to the captains of industry who have recklessly exploited the industries and transportation systems they control, Roosevelt is and has been an undoubted menace.

“Bankers, as a rule, are not business men. A business education is not derived from a counting-room training. If bankers, as a rule, were business men, they would have kept their dollars in the channels of general business circulation in lieu of chasing them into a ‘jackpot’ in Wall Street in a game in which they did not even draw cards.

“A hundred thousand speculators consider the other 79,900,000 of us as cows, existing solely for the purpose of being milked for their benefit, and when the patient cow kicks, and particularly if the kick happens to take the milker amidships, the moaning is long and loud.”

In 1909, when Roosevelt left office, the men who ran America’s trusts thought they could relax. Their relief was short-lived, though. The man who succeeded Roosevelt — who had been called “the Great Trust Buster” — was William Howard Taft. For a time, Taft was an even greater menace. He broke up more trusts in four years than Roosevelt did in seven-and-a-half.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Certainly a sign of the MAGA insurrectionist leanings of the Post. Because he worked for the public benefit and tamed business monopolies, the fascist Republican Party has publicly repudiated him. Declare the Republicans a terrorist organization and destroy them. Thank God you are so irrelevant that no one reads it.