This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As I’ve argued before, in this column and elsewhere, Labor Day isn’t just the unofficial end of summer or an occasion for barbecues and ballgames — it’s an opportunity to remember the histories of the labor movement. Those collective memories can’t just be commemorations, however; they also have to engage with the movement’s complexities and contradictions, its flaws and failures as well as its successes and legacies. Certainly organized labor has not been exempt from the influence of white supremacy, for example, as illustrated by its overt and all-too-often central role in discriminatory moments such as the Chinese Exclusion era of the late 19th century.

Challenging those white supremacist narratives doesn’t simply require remembering them, though. It also depends on expanding our vision of the labor movement to include all American communities, throughout all of American history. If we link the histories of slavery and enslaved workers to labor and the labor movement, for example, we can better understand the true interconnectedness of all Americans in the process.

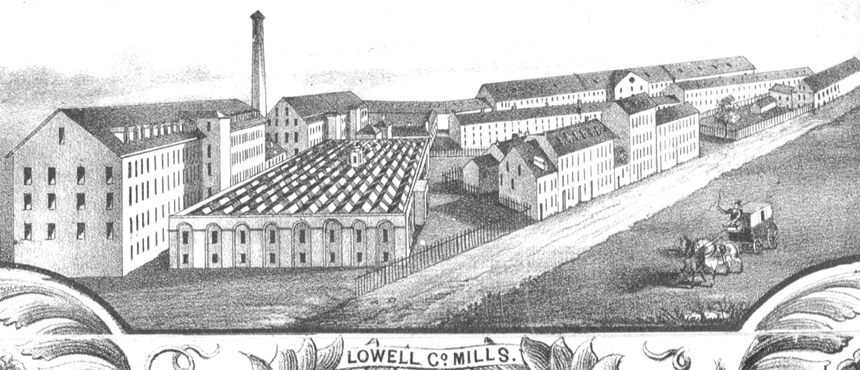

For one thing, viewing enslaved workers as a community of laborers helps us reimagine enslaved resistance and rebellion as an inspiring form of labor activism. The early 19th century is often defined as the origin point for the organized labor movement in America — as the Industrial Revolution commenced and workers began to gather in greater numbers in spaces such as the Lowell Mills, those communities began to find their collective voices and power. As early as 1834 women workers at those mills went on strike, leading to the formation of the influential Lowell Female Labor Reform Association.

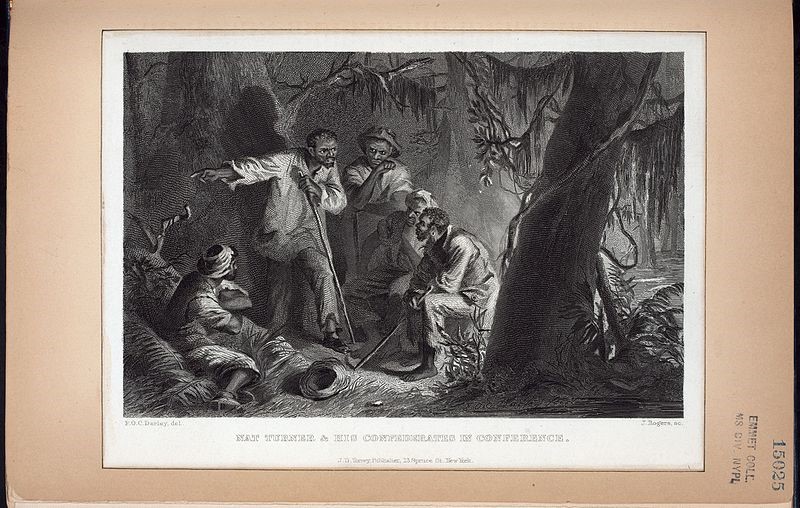

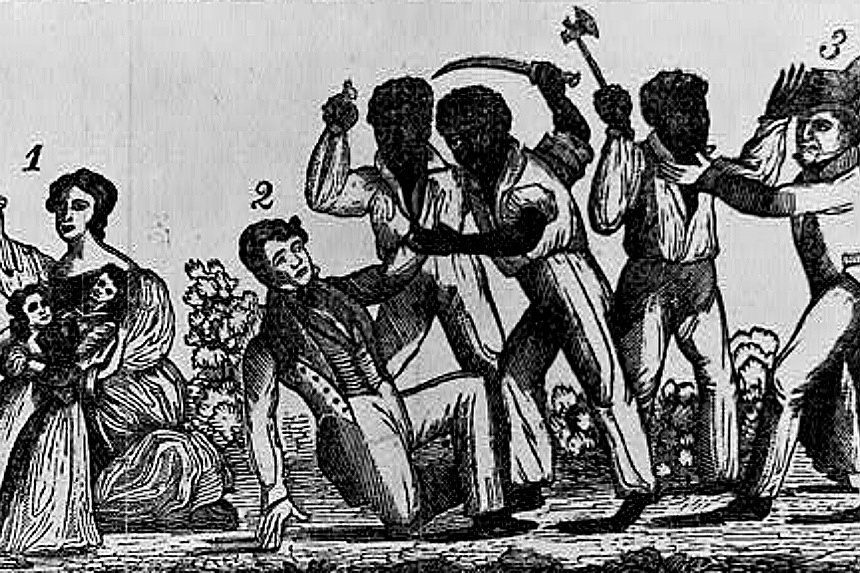

But this time period also witnessed one of the most well-organized and largest slave revolts in American history, the Southampton Insurrection (also known as Nat Turner’s Rebellion). In August 1831 the enslaved preacher and activist Nat Turner organized and led more than 70 men, both enslaved and free, in a collective action for freedom and vengeance that left more than 50 white Virginians dead. While the rebellion’s overt violence of course differentiates it from the Lowell labor action, this too was a movement of workers protesting and resisting inhumane conditions and seeking to exercise their voice and power in the only ways available to them. Although Turner and his movement were, like the Lowell strikers, shut down by their overseers, they too left a lasting influence on future activists, as illustrated by the escaped slave and abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet’s invocation of Turner as “patriotic” in his 1843 National Negro Convention speech calling for all enslaved people to rise up in a collective action of mass resistance.

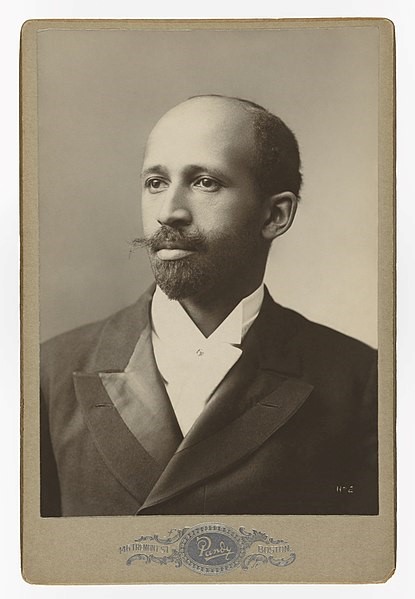

Another example of massive resistance from enslaved Americans was during the Civil War. Historians have increasingly come to argue that the Civil War did indeed feature such labor actions in a central and influential way. It was W.E.B. Du Bois who first advanced this idea, arguing at length in his magisterial book Black Reconstruction in America (1935) for the thesis that enslaved people undertook a “general strike” during the later years of the Civil War, which directly contributed to both that war’s successful conclusion and to their own emancipation:

How the Civil War meant emancipation and how the black worker won the war by a general strike which transferred his labor from the Confederate planter to the Northern invader, in whose army lines workers began to be organized as a new labor force.

Later in the chapter he writes that this “was a strike on a wide basis against the conditions of work. It was a general strike that involved directly in the end perhaps half a million people.”

In his own era, Du Bois was alone in making this case, not least because it sought to re-center narratives of the Civil War’s triumphs and effects from white soldiers, sacrifices, and national unity to enslaved people, labor activism, and emancipation. But over the last few decades, more and more historians and scholars have extended this vision of the war, from the groundbreaking 1992 collection Slaves No More: Three Essays on Emancipation and the Civil War to Chandra Manning’s What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War (2007) to David Williams’ I Freed Myself: African American Self-Emancipation in the Civil War Era (2014). These and many other scholarly works have built on Du Bois not only in reframing the Civil War and emancipation, but also in recognizing that enslaved people were a community of American workers who had a significant say in their own future, before, during, and after the war.

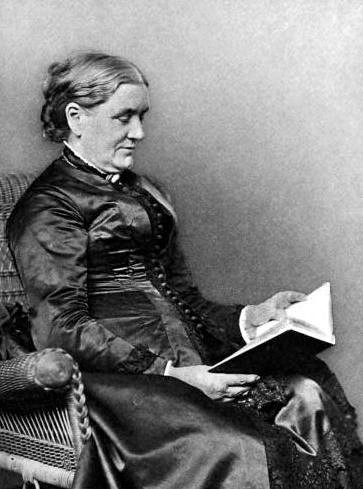

Connecting enslaved people to the labor movement doesn’t just reframe the history of slavery, Civil War, and emancipation. It also forces us to think about the interconnections between communities of American workers. Offering a vital contribution to that reimagining process is a powerful poem written during the Civil War, Lucy Larcom’s “Weaving” (c.1862). Larcom herself was one of those aforementioned Lowell Mill workers and a founding contributor to The Lowell Offering, the short-lived but groundbreaking monthly periodical that featured the voices of those working women. After leaving the mills, Larcom would go on to a long career as a teacher as well as a poet, and in “Weaving” she ties together all those roles, writing about the complex and crucial interconnections of mill workers and enslaved people.

The subject of Larcom’s poem is an unnamed woman worker at the Lowell Mills who “stands before her loom,” looking out onto the Merrimack River and reflecting on her own work and identity. But as she does so, her thoughts wander South to “sunnier streams than thine” where “My sisters toil, with foreheads black;/And water with their blood this root,/Whereof we gather bounteous fruit.” Larcom engages here with a very real historical issue: the cotton used in Lowell and throughout the North was produced by enslaved labor in the South, deeply interconnecting these regions even as the era’s debates and build-up to war seemingly divided them. But through that context Larcom considers the even deeper connections between these American women, links that she wants all Americans to recognize more fully: “weary weaver, not to you/Alone was war’s stern message brought:/‘Woman!’ it knelled from heart to heart,/‘Thy sister’s keeper know thou art!’”

At its core, the labor movement was defined by the idea that Americans are each other’s keepers; that workers look out for each other, not just within particular industries but throughout the nation; and that the well-being of American workers is inseparable from our collective success.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

There is a lot to look at and into here. This feature shows that much of what we thought of as ‘separate’ historical incidents and events were actually tied together, and influenced each other far more than we realized. Lucy Larcom alone is a perfect example. I intend to look into this more, starting with your helpful links here.