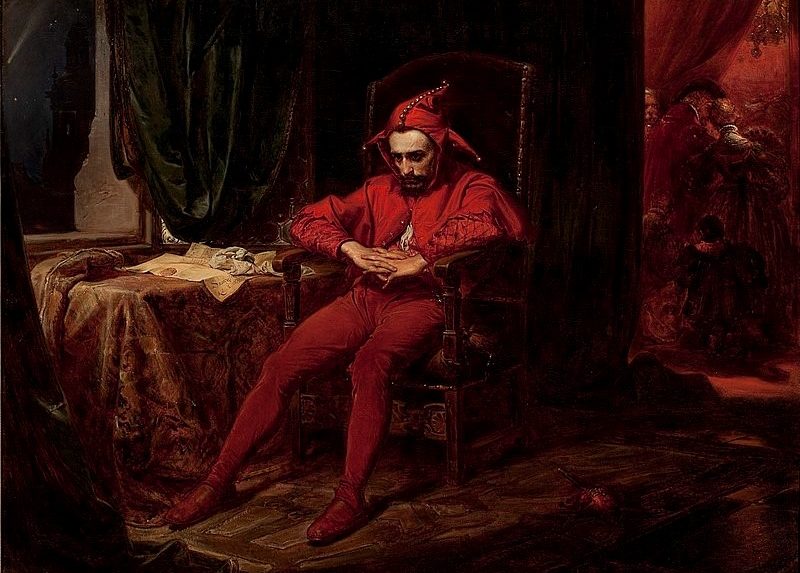

One of Shakespeare’s conceits is the wisdom of clowns. From Feste in Twelfth Night to the Fool in King Lear, they speak truth to power, but tell it slant and do so at their peril.

The stabbing last month of Salman Rushdie, who lived under threat of a decades-long fatwa for his comedic novel, The Satanic Verses, and Will Smith’s Oscars stage assault on Chris Rock remind us that satire is risky business: One person’s hilarity is another’s sacrilege. Satirists, comics, and fools are ideological pathfinders, risking their reputations, and sometimes their health and security, to chart terrain for the rest of us. Comedians are America’s modular, detachable consciences, at times challenging the status quo, at times serving it.

In his critique of pre-Enlightenment culture, Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin argued that long before America’s Bill of Rights enshrined free speech, “comic rites and cults, the clowns and fools, giants, dwarfs, and jugglers, the vast and manifold literature of parody” formed a sanctioned resistance to the “official and serious tone of medieval ecclesiastical and feudal culture.”

Fools were stabilizing forces in downtrodden societies, enabling peasant classes to lampoon the rich and vent their discontent with poverty, disease, violence, and a totalitarian church and state — within the bounds of stages and jokes.

Americans, too, have relied on comedians for subversive apprehensions of our national circumstance. Thomas Paine’s wry voice of American common sense planted seeds of our first revolution. American humor also served a unifying function after the Civil War and the end of chattel slavery, and again in the face of expanding American imperialism in Mark Twain’s satire.

Nineteenth-century America’s jester was the blackface minstrel, his artform employing comic skits and dancing, and freighted with tragic irony. Most minstrels were white men — often Irish and Italian immigrants — who caricatured the physicality of African slaves and freedmen, who had themselves developed show dance forms like the cakewalk to parody the mannerisms of white people. Like Bakhtin’s fools, minstrels performed a kind of acceptable populist subversion that gave rise to blackface literature like, for instance, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s landmark Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and a century later, dissident narratives such as Norman Mailer’s The White Negro, which called for (white) people to abandon postwar conformity for a more rebellious outlook, which Mailer associated with Black people.

Despite being compromised by the racist tropes of its era, minstrelsy amplified a bevy of art forms including jazz, tap dance, and the blues, which were also deemed subversive due, in part, to their origins in Black culture. Minstrel shows also featured authentic African American talents including Scott Joplin, who was known as the King of Ragtime; Gertrude “Ma” Rainey; and Charley Case, who is sometimes credited with inventing stand-up comedy.

Case’s father was an African American musician; his mother was Irish American. At a time when much of America fell under Jim Crow anti-miscegenation laws, Case performed unadorned narrations about his mixed heritage family while casually twisting a bit of string around his fingers. He became one of the nation’s highest-paid performers, and yet, off-stage, Case was known for his brooding, morose nature. He shot himself to death in a hotel room in 1916.

Today, America’s comedians have assumed the mantle of public intellectuals. Whether or not one agrees with them, their collective voices are arguably more pervasive and influential than those of traditional intellectuals like Nicholas Kristof or Ayaan Hirsi Ali. And like Bakhtin’s clowns, modern comedians play a dual role in our society — sometimes stabilizing it, and other times challenging cultural norms.

On the day Donald Trump was elected president, Dave Chappelle and Chris Rock appeared on Saturday Night Live to leaven what seemed a hopeless situation for half of the country’s voters. Rock ridiculed liberals’ surprise that Hillary Clinton lost; Chappelle struck a conciliatory note: “I’m wishing Donald Trump luck, and I’m going to give him a chance. And we, the historically disenfranchised, demand that he give us one, too.” (Chappelle later apologized for his naivete.)

And after at least 59 people were killed in Las Vegas in 2017, victims of the country’s deadliest mass shooting by a single gunman, survivors appeared on Ellen DeGeneres’ talk show to make sense of the carnage.

In both instances, American stand-up comics helped smooth out high-stakes incidents. In other situations, comedians tested societal boundaries. DeGeneres herself went against the grain when she came out as a lesbian 25 years ago, depicting the first openly gay character on primetime television. As billionaire British Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling desperately rejected accusations that she was a “TERF,” Chappelle defended her and said he identified with that title. Comedian podcaster Joe Rogan has interviewed some of the nation’s most canceled figures — from a vocal vaccine skeptic to conspiracy theorist Alex Jones — inviting widespread protests and commanding ever larger audiences.

One of the reasons that comedians appeal to us so much, however, is that their intellectualism is played, first and foremost, for laughs. Comedy is performative, and whatever views they express may not be “real,” but all an act. “I talk shit for a living,” Rogan said in a stand-up routine earlier this year. “If you’re taking vaccine advice from me, is that really my fault? If you want my advice, don’t take my advice.”

Comedians’ riffs on sexual assault, gender identity, electoral politics, abortion, or any other off-limit discourses are creating new canons of critical literature, displacing the intellectual takes of popular academics of the past. But unlike treatises of old, when Jon Stewart rants about bat coronaviruses and burn pits, or Bill Burr takes on abortion rights, millions are listening, watching, guffawing, and sometimes, even agreeing.

Ask yourself: When was the last time you wanted to know what Francis Fukuyama, Noam Chomsky, or Cornel West thinks about a given topic? You’re more likely to wonder what HBO’s Real Time host Bill Maher said about it. It’s no accident that America’s most popular cable news program, Fox’s The Five, employs comedian Greg Gutfeld to speak about current events. The second most-watched cable news show is Tucker Carlson Tonight, which bounces between rightward diatribes and satirical snark.

In the age of social media, where a wrongfooted sentence can conflagrate a career built over a lifetime, comedians are our ideological crash-test dummies. They press the limits of permissible speech and thought, they challenge social convention, they test our boundaries, and make us roar when they tell us what we’re really thinking (but dare not say aloud).

The comedic mask allows us the liberty of laughter, without any commitment to deeper subversions. Jokes reveal hypocrisies and incite us to laugh at the nakedness of our emperors — even in front of our emperors. American comedy is a sanctioned release of social and ideological pressure, often in service to more durable authorities.

Comedians are America’s public intellectuals, sure, but they’re also just joking.

Originally published on Zócalo Public Square. Primary Editor: Talib Jabbar | Secondary Editor: Eryn Brown

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I have yet to see anything funny or well thought out by the likes of Colbert, Kimmel, and such. I’d rather watch reruns of Jack Benny and Johnny Carson. Now they were truly funny comedians and did not outwardly exhibit their political leanings for all of America to see. Sadly, we’ll never again have another comedian with such class.