This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Last Wednesday, the Ohio House of Representatives passed one of the nation’s most aggressive and egregious anti-transgender laws to date. Inserted into a broader omnibus bill about mentorship and education, these specific items would require transgender female high school athletes to join male or co-ed teams, and would allow any parent to challenge an athlete’s gender and then require that athlete to be subjected to a medical exam. If the bill passes the state Senate and is signed by Governor Mike DeWine, it will not only make life even more difficult for the handful of trans athletes currently competing in Ohio high school sports, but will subject all teen athletes in the state to constant scrutiny and the threat of invasive exams.

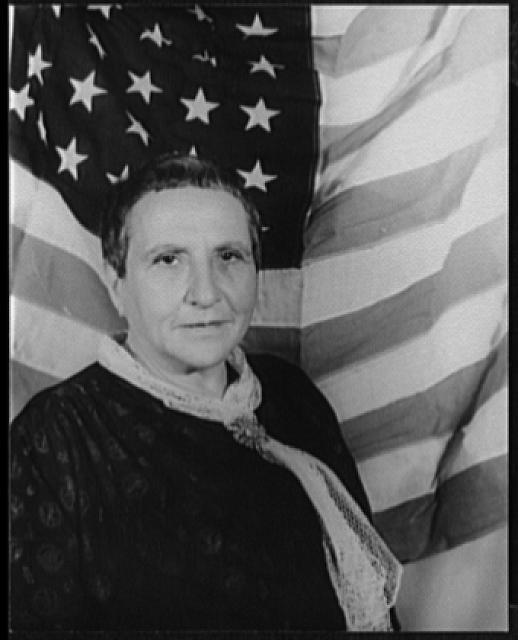

This bill would be extreme and hurtful toward young people and the transgender community at any time, but passing it on June 1st, the first day of Pride month, adds insult to injury. After all, Pride is not just a month for celebration, nor an important occasion to remember foundational histories. It’s a time to better understand, respect, and validate the experiences, identities, and very existence of LBGTQ Americans. One of the most inspiring such Americans, in her life and her literature alike, was the groundbreaking author Gertrude Stein (1874-1946).

From a young age, the precociously intelligent and ambitious Stein was unsatisfied with late 19th century images of gender identities and roles and sought to create a more gender-neutral self separate from those limitations. She described this perspective most fully in her posthumously published autobiographical work The Things As They Are (1950), detailing both the depression caused by her dissatisfaction with cultural views of femininity and her consistent attraction to qualities and experiences typically deemed “masculine.” In our own moment, Stein might have come to define herself as transgender and transition to a male identity; in her own era, with such choices out of the question, she sought out educational and social settings where she could develop and explore this unconventional sense of self.

One of those educational settings was her time at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine (between 1897 and 1901). Stein was encouraged to enroll in medical school by William James, the innovative psychologist and philosopher who had become a mentor to Stein during her time as an undergraduate at Radcliffe College. Both Hopkins specifically and the medical profession as a whole were still overwhelmingly male-dominated in the era, and Stein in particular stood out even more. One male classmate described Stein as “big and floppy and sandaled and not caring a damn.” Rather than seek to fit in, Stein pushed further still; as biographer Linda Wagner-Martin puts it, Stein’s “controversial stance on women’s medicine caused problems with the male faculty.” She also expressed those and other radical views on gender and society in a provocative 1899 speech to Baltimore women entitled “The Value of College Education for Women.”

Although Stein’s controversies at Hopkins caused her to withdraw from medical school before completing her degree, her time in Baltimore offered her a glimpse of social and romantic communities that likewise transgressed beyond the period’s expectations and limitations. Stein became very close to a fellow med student, Mabel Haynes, who was in a lesbian relationship with the young feminist activist and journalist Mary Bookstaver. Stein seems to have fallen in love with both women, better realizing her own sexuality in the process, a romantic triangle and personal experience that she would make the subjects of her first work of fiction, Q.E.D. (1903). Often described as one of the first coming out stories, Q.E.D. portrays young women’s sexualities and relationships with an honesty and intimacy that would be impressive from any writer not yet 30 years of age, and is even more striking when we consider that Stein herself had only just begun working through these themes in her own life.

After leaving Hopkins, Stein traveled to Paris with her brother Leo, a talented young artist and art collector. It was there that she would meet the young woman with whom she would create her own alternative, inclusive social setting and community. Pushed away from her childhood home in San Francisco in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake and fire, the young Jewish American musician and writer Alice B. Toklas (1877-1967) traveled to Paris in September 1907; on her first day in the city she met Gertrude Stein, and the two began a relationship that would endure until Stein’s death. For the next few decades Stein and Toklas turned their Paris home into a salon, welcoming artists, authors, and activists for groundbreaking conversations and community that would, as a biographer of the photographer Carl Van Vechten puts it, “help define modernism in literature and art.”

Stein would also turn her relationship with Toklas into the basis for perhaps her most fully realized book, and one that likewise defined a new modernist literary form. The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933) combines fiction and biography, bringing together Stein’s authorial style and the narrative voice of Toklas (also created by Stein, it seems) to tell the stories of each woman prior to their arrivals in Paris, of their meeting and evolving relationship, and of the home, salons, and community that they built together. Autobiography thus has a great deal of cultural and historical as well as literary value, but most of all it builds on Q.E.D. to portray a same-sex romantic relationship and partnership with honesty and intimacy, depth and power, humor and pathos, and as much humanity as we see of any romance in any Modernist classic.

Neither Q.E.D. nor Autobiography was Stein’s most groundbreaking LGBTQ literary work, however. That honor would have to go to “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene,” a short story first published in the July 1923 issue of Vanity Fair. Subtitled “The Tale of Two Young Ladies Who Were Gay Together and How One Left the Other Behind,” Stein’s story is quite possibly the first published work to use the word “gay” to describe same-sex relationships; the word appears over 100 times in the brief story, a particularly striking and significant example of Stein’s frequent use of extreme repetition in her writing. She detailed her perspective on that element in a 1934 speech at the University of Michigan, noting, “I am inclined to believe that there is no such thing as repetition. The inevitable seeming repetition in human expression is not repetition, but insistence.”

In her life and her literature alike, Stein insisted that same-sex relationships, identities outside of the conventional bounds of gender, and other LGBTQ experiences and communities be treated as thoughtfully as all other human experiences.

Featured image: Gertrude Stein (Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now