In the years following Norman Rockwell’s success at The Saturday Evening Post, American illustration changed dramatically. Pictures that Rockwell created with oil paint on canvas were gradually replaced by “photo illustrations.” Today, illustrators are able to make pictures with computers to put in magazines that arrive on the internet rather than in the mailbox. Digital images now pop up off the page in holograms, and artists sell NFTs (non-fungible tokens), electronic art that requires enough electricity to run a refrigerator for a year.

But the heart of illustration will always be its creativity, not its gadgetry. Just ask award-winning artist Gary Kelley.

Kelley is one of the most successful Illustrators of his generation. He is no software engineer working in Silicon Valley; instead, he has enjoyed a long and prestigious career working from a town in Iowa not far from where he was born. He still uses traditional media such as pastels and oil paint, but his ideas are new.

As a boy, Kelley was inspired to draw by reading Tonto comic books about the Lone Ranger’s faithful companion. He recalls that he learned even more about drawing from art books owned by a favorite uncle. He also studied the illustrations that arrived in The Saturday Evening Post every week, recalling that those illustrators “were my first heroes.” Kelley earned a BA in art from the University of Northern Iowa, where he focused on painting and design. He began his career as a graphic designer and art director but soon found his way to illustration.

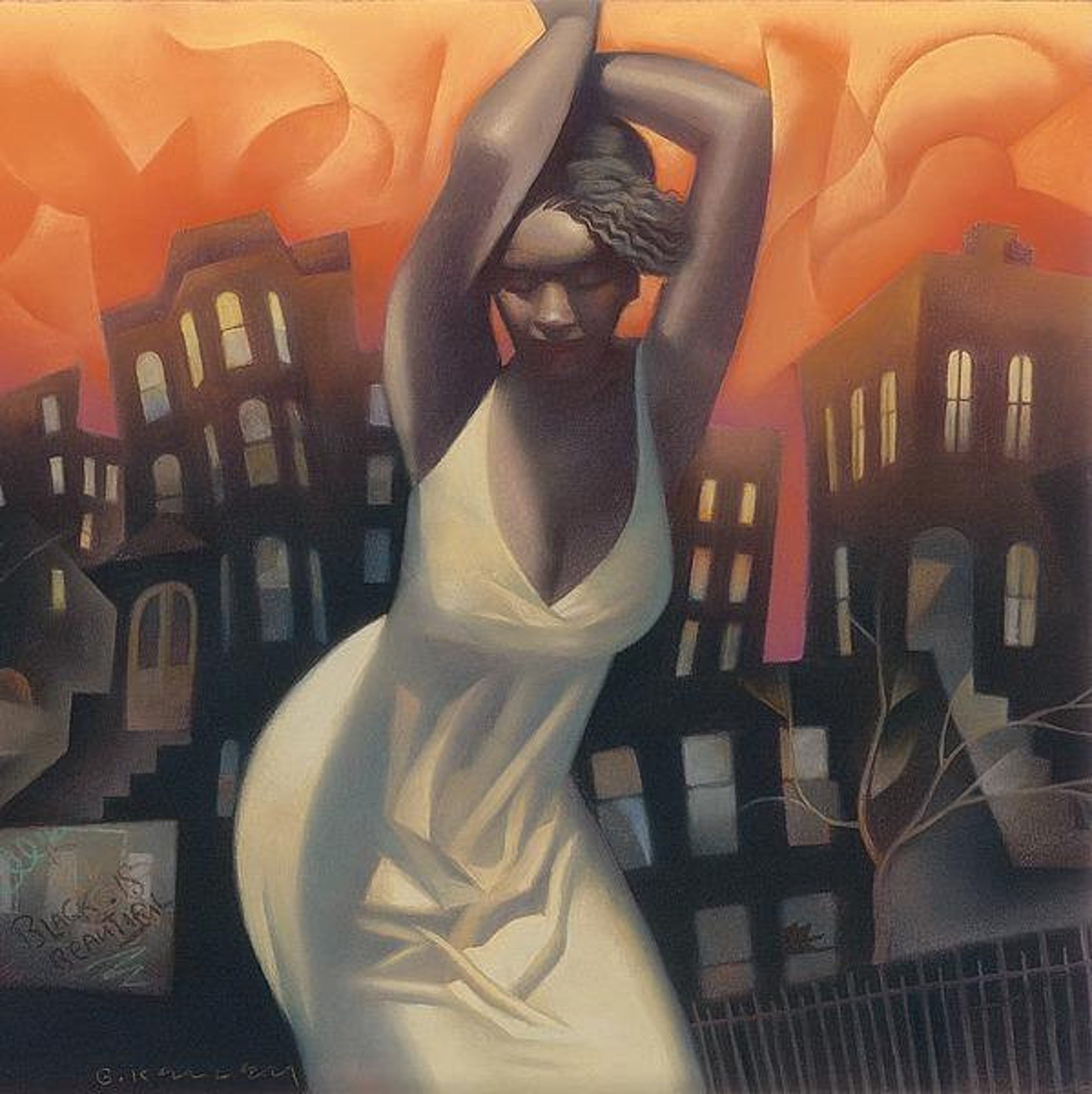

Illustrating for advertisements paid the best, but was not always the most fun. Kelley was more inspired by the drama and the storytelling aspects of art. For him, that’s what made illustration fun and interesting.

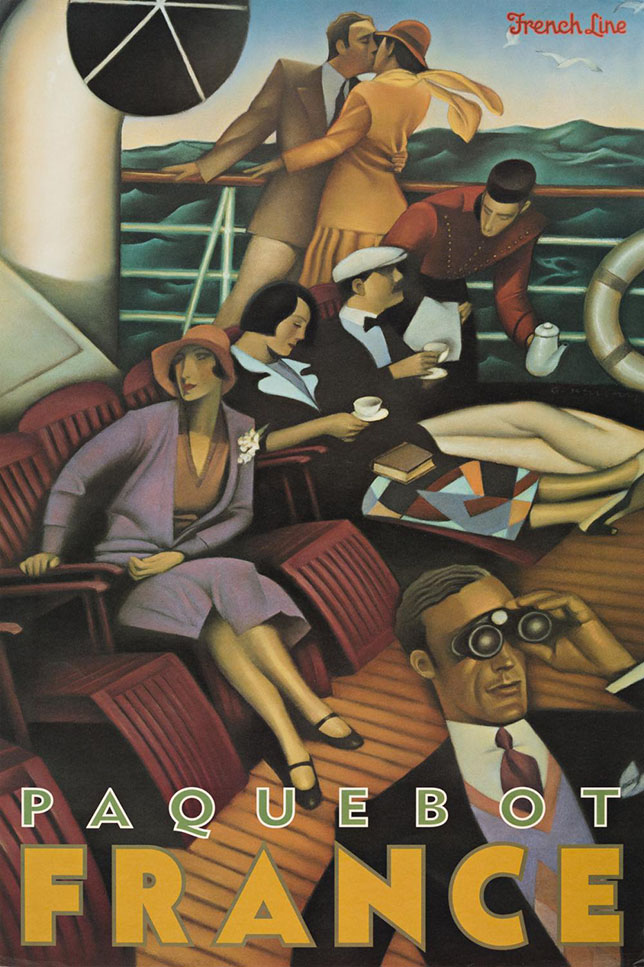

He started by illustrating stories for Better Homes and Gardens magazine and went on to create pictures for major publications such as Time, Rolling Stone, Atlantic Monthly, The New Yorker, Playboy, The Los Angeles Times and The Boston Globe. Many of these publications traditionally hired artists from major urban centers, but if you’re good enough they will seek you out in a small town in Iowa.

Kelley turned out to be quite good indeed. His many awards have included 27 gold and silver medals from the Society of Illustrators in New York. His art has been exhibited in museums internationally, from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington and the Art Institute of Chicago to the Creation Gallery in Tokyo and the Pablo Neruda Cultural Center in Paris. Not surprisingly, the Norman Rockwell Museum in Massachusetts has also displayed his art. He was elected to the Society of illustrators Hall of Fame in 2007.

As the field of illustration changed, Kelley’s projects changed too. With fewer magazine stories to illustrate, he turned to creating a series of murals for the national bookstore chain Barnes & Noble. He also illustrated a number of books, such as Rip Van Winkle, Edgar Allen Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination and Macbeth for Young Readers. More recently he has written and illustrated graphic novels such as Moon of the Snowblind, the story of the 1857 Spirit Lake Massacre, and his forthcoming Bach and the Blues.

But perhaps the most interesting innovation was Kelley’s attempt to illustrate music.

Kelley recalls that he was listening to The Planets, the 1917 orchestral suite by the English composer Gustav Holst, when images began to appear in his mind.

To Kelley, the music seemed like a soundtrack, so he decided to see if he could create pictures that embodied the qualities of the music. He said, “I’m going to see what happens,” which should be the motto of every artist.

He free associated a series of beautiful pictures to be projected on a huge screen above an orchestra while it performed. He found a willing partner in the WCF Symphony Orchestra, and the rest is history.

The Planets Reimagined – The New Live – Gary Kelley Interview (uploaded to YouTube by Boulder Phil Videos)

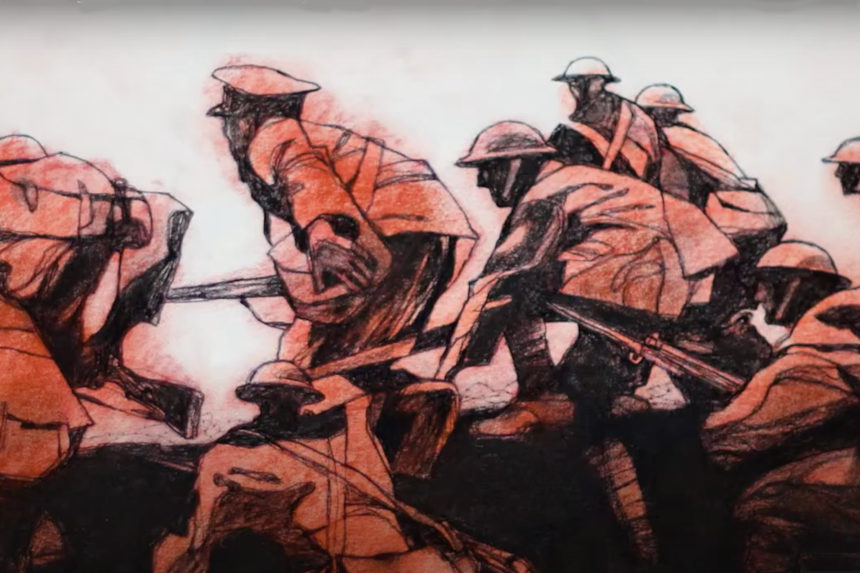

Because Mars was the Roman god of war, he created blazing images of war to accompany Holst’s section on Mars. The camera and the pictures moved, but the pictures were not animated.

The illustrated music proved to be popular, The Planets were followed by Antonin Dvořák’s New World Symphony, Gustav Mahler’s Nachtmusik, Tchaikovsky’s the Nutcracker Suite, and even music by Duke Ellington. Kelley’s musical tastes are diverse.

The lesson here is that when a creative artist wants to get innovative, they don’t have to use computers or relocate to a trendy artists’ colony. A true artist can find all the creativity they want, right where they are.

Featured image: One of Kelley’s images of war to accompany Gustav Holst’s section on Mars from his symphony The Planets (Image by permission of the artist)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

David Apatoff’s “Art of the Post” essays are delightful; I arrived on this site a recent aficionado-come-lately of J.C. Leyendecker’s richly allegorical illustrations and found myself still here an hour later, in awe of the breadth and variety of work by dozens of artists that The Saturday Evening Post, with such foresight, has so lovingly preserved. I may be reading these all morning. Apatoff’s subtle insights and keen observations, generously delivered in The Post’s clear and direct voice, give us a real sense that the art reflects a genuinely American heritage we all may share with a sense of wonder and gratitude.

Thank you David, for this feature on Gary Kelley. I had not been familiar with his work previously and am very glad to be now. His range of styles is astonishing. We don’t usually associate music with literal art, but this is a case where we see a beautiful direct cause and effect by the artist from the collaboration.