The world confronts “an epochal transition.” Or so the consulting firm McKinsey and Company crowed in 2018, in an article accompanying a glossy 141-page report on the automation revolution. Over the past decade, business leaders, tech giants, and the journalists who cover them have been predicting this new era in history with increasing urgency. Just like the mega-machines of the Industrial Revolution of the 19th and early 20th centuries — which shifted employment away from agriculture and toward manufacturing — they say that robots and artificial intelligence will make many, if not most, modern workers obsolete. The very fabric of society, these experts argue, is about to unravel, only to be rewoven anew.

So it must have come as a shock to them when they saw a recent U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) report, which debunks this forecast. The agency found that between 2005 and 2018 — the precise moment McKinsey pinpointed as putting us “on the cusp of a new automation age” — the United States suffered a remarkable fall-off in labor productivity, with average growth about 60 percent lower than the mean for the period between 1998 and 2004. Labor productivity measures economic output (goods and services) against the number of labor hours it takes to produce that output. If machines are taking over people’s work, labor productivity should grow, not stagnate.

The BLS, in stark contrast to management consultants and their ilk, is typically restrained in its assessments. Yet this time, its researchers called cratering productivity “one of the most consequential economic phenomena of the last two decades … a swift rebuke of the popular idea of that time that we had entered a new era of heightened technological progress.”

Many ordinary people have encountered this paradox: They are underemployed or unemployed but also, counterintuitively, working harder than ever before. Historically in the U.S., this phenomenon has always typically accompanied public discussions of “automation,” the ostensible replacement of human labor with machine action. Mid-20th-century automobile and computer industry managers often talked about “automation” in an effort to play off the technological enthusiasm of the era. But rather than a concrete technological development and improvement, “automation” was an ideological invention, one that has never benefited workers. I use scare quotes around “automation” as a reminder that the substance of it was always ideological, not technical. Indeed, from its earliest days, “automation” has meant the mechanized squeezing of workers, not their replacement.

Which is why, ever since the end of World War II, what employers have called “automation” has continued to make life harder, and more thankless, for Americans. Employers have used new tools billed as “automation” to degrade, intensify, and speed up human labor. They have used new machines to obscure the continuing presence of valuable human labor (consider “automated” cash registers where consumers scan and bag their own groceries — a job stores used to pay employees to do — or “automated” answering services where callers themselves do the job of switchboard operators). “All automation has meant to us is unemployment and overwork,” reported one auto worker in the 1950s; another noted that “automation has not reduced the drudgery of labor … to the production worker it means a return to sweatshop conditions, increased speedup, and gearing the man to the machine, instead of the machine to the man.”

There is no better example of the threat and promise of “automation” than the introduction of the beloved electronic digital computer. The first programmable electronic digital computers were invented during the Second World War to break Nazi codes and perform the enormous calculations necessary for the construction of an atomic bomb. Well into the early 1950s, computers remained for the most part associated with high-level research and cutting-edge engineering. So, at first, it was by no means obvious how a company might use an electronic digital computer to make money. There seemed little computers could offer businessmen, who were more interested in padding profits than decrypting enemy ciphers.

It was left to management theorists, hoping to build up and profit from the budding computer industry, to create a market where none yet existed. First among them was John Diebold, whose 1952 book Automation not only made “automation” a household term, but also introduced the notion that the electronic digital computer could “handle” information — a task that until then had been the province of human clerical workers. “Our clerical procedures,” wrote Diebold, “have been designed largely in terms of human limitations.” The computer, he told a new generation of office employers, would allow the office to escape those human limits by processing paperwork faster and more reliably.

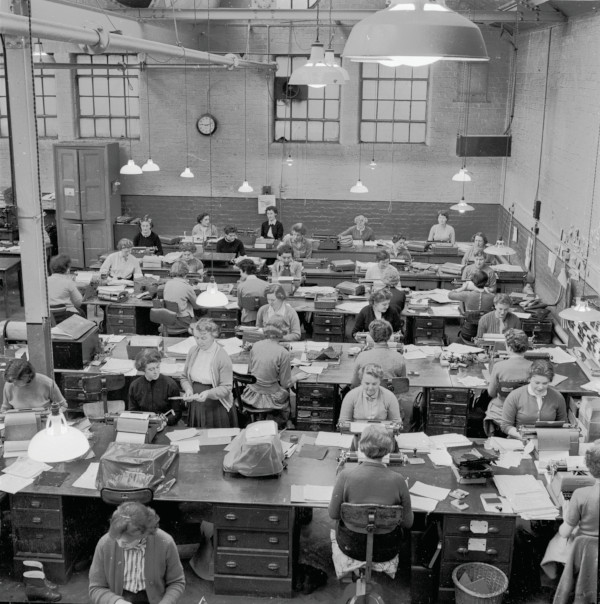

Office employers of the early 1950s found this message attractive — but not because of the allure of raw calculating power or utopian fantasies of machines that automatically wrote finished briefs. They were worried about unionization. With the end of the Second World War and the rise of U.S. global power, American companies had hired an unprecedented number of low-wage clerical workers to staff offices, the vast majority of them women (who employers could pay less because of sexist norms in the workplace). Between 1947 and 1956 clerical employment doubled, from 4.5 to 9 million people. By 1954, one out of every four wage-earning women in the U.S. was a clerical worker.

The boom in low-wage clerical labor in the office suite shook employers. Not only were payrolls growing, but offices increasingly appeared ever more proletarian, more factory floor than management’s redoubt. Business consultants wrote reports with titles such as “White-Collar Restiveness — A Growing Challenge,” and office managers started to worry. They installed computers in the hopes they might reduce the number of clerical workers necessary to run a modern office — or, as they put it, they bought computers in the hopes they could “automate” office labor.

Unfortunately for them, the electronic digital computer did not reduce the number of clerical workers it took to keep an office afloat. In fact, the number of clerical workers employed in the United States continued to swell until the 1980s, along with the amount of paperwork. In the late 1950s, one manager complained that with computers in the office, “the magnitude of paperwork now is breaking all records” and that there were “just as many clerks and just as many key-punch operators as before.” While computers could process information quickly, data entry remained the task of the human hand, with clerical workers using keypunch machines to translate information onto machine-readable cards or tape that could then be “batch” processed.

Unable to remove human labor from office work, managers pivoted back to something they had done since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution: They used machines to degrade jobs so that they could save money by squeezing workers. Taking a page from the turn-of-the-20th-century playbook around “scientific management” — where manufacturing employers prescribed and timed every movement of the worker at their machine down to the fraction of a second — employers renamed the practice “automation”; and again, instead of saving human labor, the electronic digital computer sped up and intensified it. “Everything is speed in the work now,” one clerical worker in the insurance industry complained. Mary Roberge, who worked for a large Massachusetts insurance company in the 1950s, described a typical experience. In her office, there were 20 female clerical workers for every male manager. The clerical staff “stamped, punched, and endlessly filed and refiled IBM cards.” Bathroom breaks were strictly limited, and there were no coffee breaks. American employers gradually phased out skilled, well-paid secretarial jobs. Three out of every five people who worked with computers in the 1950s and 1960s were poorly remunerated clerical workers. Roberge made $47.50 a week, which, adjusting for inflation, would be less than $22,000 a year today. “That was extremely low pay,” she later reflected, “even in 1959.”

And yet in public, employers and computer manufacturers claimed that no one was performing this work, that the computer did it all on its own — that office work was becoming ever more “automated.” As one IBM promotional film put it: “IBM machines can do the work, so that people have time to think. … Machines should work, people should think.” It sounded nice, but it simply wasn’t the case. “Automation” in the American office meant that more people were being forced to work like machines. Sometimes this allowed employers to hire fewer workers, as in the automobile, coal mining, and meatpacking industries where one employee now did the work of two. And sometimes it actually required hiring more people, as in office work.

This remains the story of “automation” today.

Take Slack, an online “collaboration hub” where employees and their managers share a digital space. On its website, the company depicts the application as a tool that offers employees “the flexibility to work when, where and how you work best.” But the communication platform, of course, is the very tool that allows employers to compel workers to labor at home and on vacation, at the breakfast table in the morning, and riding the commuter train home at night.

Seventy years ago, bosses made employees use computing technology to get them to work more, for less. It’s a legacy that repackages harder and longer work as great leaps in convenience for the worker, and obscures the continued necessity and value of human labor. Rather than McKinsey’s “epochal transition,” the new world of automation looks all too familiar.

Jason Resnikoff is a lecturer in the history department at Columbia University and author of Labor’s End: How the Promise of Automation Degraded Work.

Originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square (zocalopublicsquare.org)

This article is featured in the May/June 2022 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

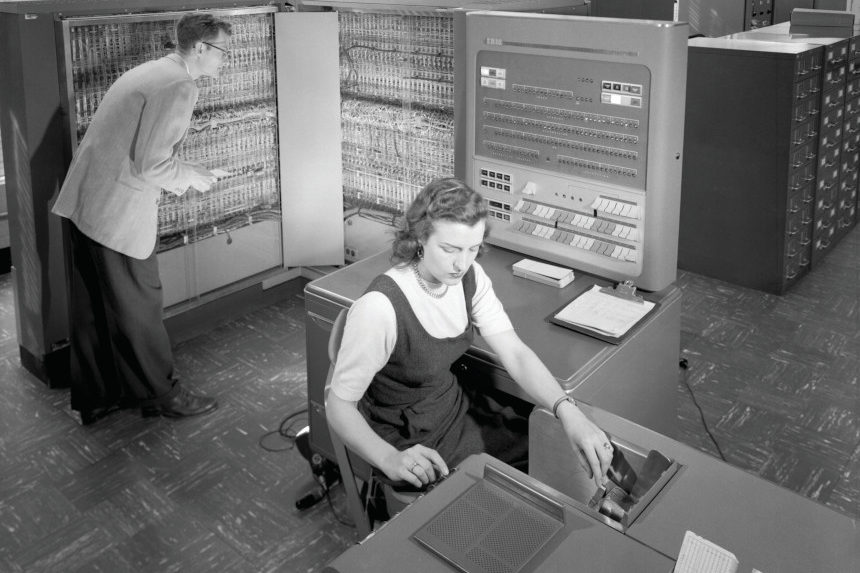

Featured image: Big Blue: The massive IBM Electronic Data Processing Machine introduced in 1954. (NASA Archive / Alamy Stock Photo)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I think the focus on automation as the root of employees work longer and harder is caused by competition directly connected to globalization. Automation makes our country more competitive.

Additionally, the reason for lower productivity while increasing automation is simply the increase complexity of our products and services.

It seems that Jason Resnikoff’s opinions on the current automation is based on historical (industrial age) perspectives, and not on the understanding of Intelligent Automation and AI.