Here we are again. On an almost annual basis, a firestorm surrounding the notion of books being banned reignites somewhere in America. The most frequent battlegrounds are public and school libraries, with the fields of engagement including venues like school board meetings and town halls. Such a recurring cycle poses two questions: what are the most frequently banned or challenged books in the United States, and why?

The leading authority on tracking book bans and challenges in the United States is the American Library Association. A non-profit founded in 1876, the ALA promotes libraries and library education; it’s the oldest such group in the world. Some of the organization’s guiding principles are articulated in both the Library Bill of Rights and the Freedom to Read Statement. The LBR was drafted in 1939 and includes, in its third article, a stance against censorship. Freedom to Read was adopted in 1953 and lists as its first proposition: “It is in the public interest for publishers and librarians to make available the widest diversity of views and expressions, including those that are unorthodox, unpopular, or considered dangerous by the majority.” The ALA is always in the forefront of advocacy to prevent bans, and they maintain databases and lists of challenged books (according to the ALA, “a challenge is an attempt to remove or restrict materials, based upon the objections of a person or group. A banning is the removal of those materials”).When considering the question of which books have been challenged the most, it might be easier to ask, “What hasn’t been challenged?” Here’s a look at three categories: frequently challenged classics, the most challenged books of the 2000s, and the most challenged books of 2020 (the most recent year with complete data).

The Classics

The ALA uses the Columbia Publishing Course (formerly the Radcliffe Publishing Course) list of the Top 100 Novels of the 20th Century as the starting point for its “Banned and Challenged Classics” list. The Course (now based at Columbia University) is the most prestigious program of its kind, turning out many top editors in publishing. Near then end of the 1990s, the Course assembled a list of selections for top novels, and the ALA notes when any of those books have been challenged for bans. At present, 46 of the top 100 have been challenged or protested at public or school libraries.

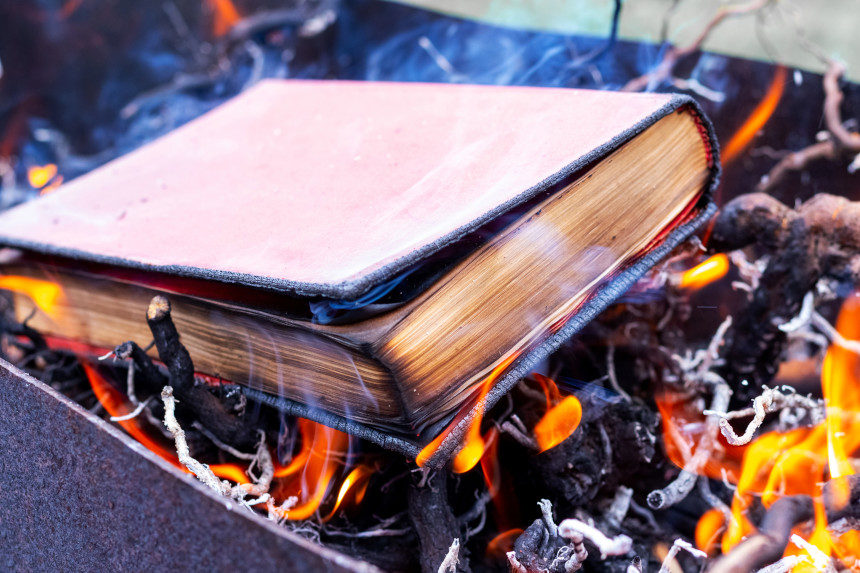

In a January 28, 2022, thread on Twitter, Carnegie Mellon Professor Kathy M. Newman, who teaches a course on banned books, wrote, “Book banning in the United States happens the most frequently in five places: classrooms, schools, school districts, school boards, and public libraries. Challenges to books are almost always brought by public school parents.” The lists of reasons as to why books get challenged are long and varied, but frequent topics listed by the ALA include strong language, ethnic slurs, depictions of sex or sexuality, violence, or even “moral content.” J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings was burned “as satanic” outside Christ Community Church in Alamagordo, New Mexico in 2001 (incidentally, the same year that part one of the blockbuster film adaptation, The Fellowship of the Ring, was released).

Among the classics with the largest number of challenges are J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, George Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, William Golding’s The Lord of the Flies, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men, and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five. Some authors, like Toni Morrison and Ernest Hemmingway, have had a number of their works challenged; for Morrison, The Bluest Eye, Beloved, and Song of Solomon appear frequently, while for Hemmingway it’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, A Farewell to Arms, and The Sun Also Rises. While these books occasionally do get removed from libraries, they frequently survive based on long-time critical esteem, and public acknowledgement of their status. Occasionally, the challenges make it to court, and some judges are reluctant to remove works of long-established literary merit.

The 2000s

The Office of Intellectual Freedom at the ALA is the section that has documented the most banned and challenged books running for over 30 years. For the decade from 2010 to 2019, they compiled a top 100 accounting that runs from the familiar (1984, Lolita) to the perhaps hilariously obvious (Go the F— to Sleep by Adam Mansbach). It’s notable that this list is for all libraries, and not just school libraries, hence the appearance of books like Fifty Shades of Grey by E.L. James. However, the top spot on the list is occupied by a frequently taught, frequently challenged book: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie. The book has been challenged for a laundry list of items, including slurs, violence, and sexual content; the book has also been challenged after accusations of sexual harassment against Alexie in 2018.

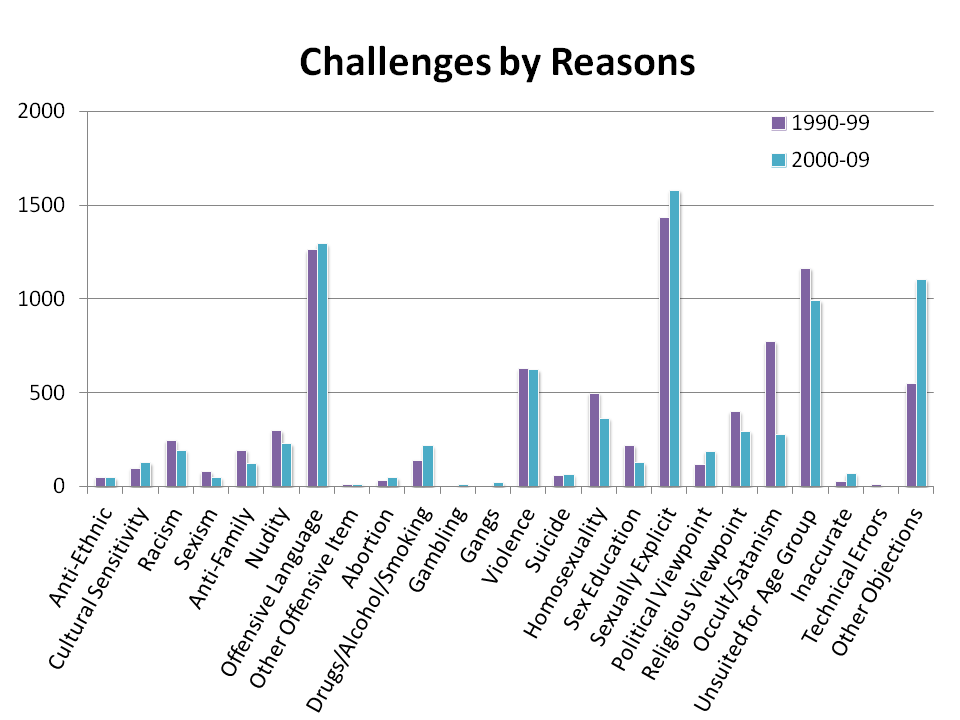

The following infographic demonstrates the nature of challenges from 1990-1999 and 2000-2009.

The Top 10, according to the ALA, are:

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

- Captain Underpants (series) by Dav Pilkey

- Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher

- Looking for Alaska by John Green

- George by Alex Gino

- And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell

- Drama by Raina Telgemeier

- Fifty Shades of Grey by E. L. James

- Internet Girls (series) by Lauren Myracle

- The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

2020

In 2020, the ALA reported that 273 books were challenged. And while some familiar entrants were on the list (hello again, Mr. Steinbeck and Ms. Morrison), topics that had been on the list prior to 2020 started making appearances. The Top Ten were:

- George by Alex Gino

- Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by and Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi

- All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely

- Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

- Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice by Marianne Celano, Marietta Collins, and Ann Hazzard

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

- Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck

- The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

- The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas

The following infographic shows, by size, the words and phrases that were used most often in more recent book challenges. Whereas in the past, depictions of sex or violence were responsible for reports, the majority of today’s complaints are directed at LGBTQ+ content or characters (regardless of depictions of sex), religious viewpoint, political viewpoint, anti-racism stances, and anti-police rhetoric (though the frequently cited The Hate U Give deals with violence committed by police).

Emily Knox is an associate professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s School of Information Sciences; she’s also the author of Book Banning in 21st Century America. In an interview with Yahoo! News from February 1, Knox elaborated on the changing motivations behind challenges. She said, “If you look at the ALA’s list, you’ll see that over the past five years, the list of most challenged books has [included] mostly what we call “diverse books.” Knox cites the definition of “diverse” used by the non-profit We Need Diverse books, explaining that diverse titles are those “including (but not limited to) LGBTQIA, Native, people of color, gender diversity, people with disabilities, and ethnic, cultural, and religious minorities.”

British daily newspaper The Guardian offers another wrinkle to the nature of book challenges in a January 24 piece by Adam Gabbatt titled, “US conservatives linked to rich donors wage campaign to ban books from schools.” The article finds links between supposedly local “grass roots” groups and a larger networked effort that appears to be aiming to remove books from schools that contain LGBTQ+, Black, Latino, Indigenous, and Asian-American narratives.

One of the key groups involved is Parents Defending Education (PDE). According to the article, “PDE’s president, Nicole Neily, was previously the executive director of the Independent Women’s Forum and worked at the Cato Institute, a rightwing thinktank co-founded by Republican mega-donor Charles Koch.” The article provides another link, noting, “[American non-profit news organization] The Intercept reported that the IWF has received large donations from Republican donor Leonard Leo, a former vice-president of the Koch-funded Federalist Society who advised Donald Trump on judicial appointments.”

Charles Koch was a key figure in the Tea Party movement that sprang up in the wake of 2008’s Great Recession. Koch and his brother, David, were involved with groups like Americans for Prosperity. In 2009, APF tied together a number of smaller groups into the broader Tea Party movement, providing central organization and funding. The playbook for Parents Defending Education is similar, as they offer templates that people can use to mount challenges to books, such as creating coordinated Instagram pages.

This creates situations where books about overcoming racism are reported for containing racist language, even in the context of the author telling the story of how certain words were used against them or their characters. Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice was reported for “divisive language” and being “anti-police” for dealing with topic of a racialized police shooting.

At this writing, the controversy around Maus, Art Spieglman’s Pulizter Prize-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust, in particular continues to swirl. As the country moves into a contentious mid-term election season, it’s a certainty that the book banning issue will continue to play a major part in the overall American narrative. The two main questions will be likely “Who writes that story?” and “Who gets to read it?”

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

You should not ban any book. If you do not like it easy do not read it everyone should have free choice as to what they read or not read , remember this is suppose to be a free country. You can not dictate that I cannot read a particular book because you have objections to it. My choice, not yours, I am not reading it out loud forcing you to hear it so shut up about it.

I’ve monitored religious broadcasters since the 90s and they never mention that one of the most frequently banned books is the Bible. It’s amazing that they never talk about this as it would fit into conservatives nonsensical claims that they are a “persecuted minority group,” but then it would contradict their claims that “no books are being banned,’ which they make every October in conjunction with the ALA’s “Banned Books Week.”

As liberal left wing snowflakes creating the cancel culture get older, so will the list of books they feel should be banned. I personally don’t want these overly sensitive idiots predetermining what my granddaughter, daughter, son, wife, or I read. We have a good mind. Let us make use of it to determine what we feel interests us and is best for us to read.

Mr. McGowan addresses the way most of us (older) adults remember learning. Stories should make people think. If a student’s parents object to a book, the rest of the class should not be deprived of this learning experience. Perhaps that student could study a different book in a different group or classroom. There is so much to learn always for the kids and for adults. Closing your eyes doesn’t resolve any problems – learning can.

This is a very slippery slope that just gets more so with each passing year. Some of these books probably should be banned, but with the sense and sensibility of decades earlier where not every-little-thing was put under a microscope of scrutiny. That’s over with (safe to say) permanently.

In the 5th grade our teacher read us both Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn books just as Mark Twain had written them, after lunch in the early afternoon. We really enjoyed them, and there was no increase in the ‘n’ word during her readings of it, or afterwards.

She explained how the proper word, ‘Negro’ was turned into something ugly, undeserved and cruel and we don’t use it for that very reason. People, particularly in the South did use it back then. Mark Twain wrote in the accepted parlance of nearly 100 years ago. Some may have used it to be cruel, but many others simply because they didn’t know better; like using ain’t when the proper word is isn’t.

Today she would be in so much trouble it would make national news and be terrible. Just use your imagination, and magnify it. In the 11th grade we read Ray Bradbury’s ‘Fahrenheit 451’ and discussing it before the teacher brought in the film to see over several days, also discussing it going along. That could never happen today. The sequences using fire were restrained and logical. The film itself (if made today instead of 1966) would be nothing but an excuse for low life maggot Michael Bay to have nothing BUT fire from beginning to end, with no let up.

‘1984’ in 12th grade had no problems, no drama around it either. Nowadays it’s probably best the parents of young children read any questionable books themselves first, or website reviews on what controversy it contains. Basically the same idea of your child wearing the mask or not being a personal decision. I love how most other nations just don’t have the continual level of drama overreacting about everything, all the time, the way we do here.