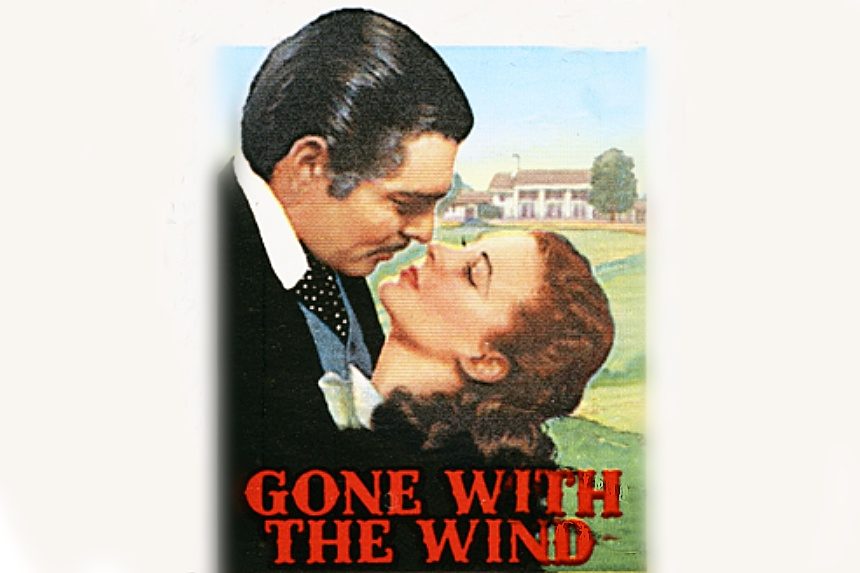

Gone with the Wind, Margaret Mitchell’s first and only novel, appeared in 1936. No phrase having to do with book sales can quantify its impact. In its first year, it went through 31 printings and sold over a million copies. Fifty years after its appearance it had sold 28 million copies and trailed only the Bible on bestseller lists. When Hollywood’s David O. Selznick set out in 1939 to produce the movie version, few thought he could bring the 1037-page book to the screen. But he did. Selznick produced a three hour and forty-five minute Technicolor epic that dwarfed the book’s profits and, if emphasis were needed, won ten Oscars including the Academy Award for Best Motion Picture of 1940.

Just over 80 years later, in June 2020, the Woke Ness Monster rose from the deep to announce that GWTW had given slavery a cinematic gloss-over — which it did. It also presented grotesque stereotypes of African-Americans. John Ridley, director of the excellent Seven Years a Slave, lit off the Tinseltown tantrum with an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times that said this: [Gone with the Wind] romanticizes the Confederacy in a way that gives legitimacy to the notion that the secessionist movement was something more, or better, or more noble than what it was — a bloody insurrection to maintain the ‘right’ to own, sell and buy human beings.” He called on WarnerMedia to remove the movie from its HBO Max arm.

Ever willing to appease Hollywood’s Cancel Culture, WarnerMedia and its parent AT&T removed the film, triggering a backlash that culminated in its reinstatement two weeks later. The corporate sycophants kept their cancelmasters at bay by adding an explanatory preamble aimed at putting GWTW into historical context.

According to the Hollywood Reporter, director Oliver Stone (JFK, Platoon, Wall Street), a somewhat larger Hollywood player than Ridley, told the BBC’s The Arts Hour that GWTW was his mother’s favorite movie and that it “should not be removed from circulation.” Stone supported the use of a disclaimer, which is fine with me.

Spike Lee, the industry’s pre-eminent African American director — and also a professor of film studies at New York University — uses Gone with the Wind and the far more overtly racist Birth of a Nation to illustrate racism as it existed in the film industry and in the nation then and now. He agrees that historical context is a valuable component in interpreting films from long ago.

Jacqueline Stewart delivers the cautionary introduction. She is professor of film and media studies at the University of Chicago and a host on Turner Classic Movies. Her words include these: “The film’s treatment of this world through a lens of nostalgia denies the horrors of slavery, as well as its legacies of racial inequality.” Stewart is African-American and I have no quarrel with her or with warning labels. But “a lens of nostalgia?” Please. A Southerner seeking nostalgia in Gone with the Wind is akin to a burglar eyeing the poorhouse.

To the extent that Southerners of the 1860s equated “states’ rights” with the right to own and keep slaves, Mr. Ridley is correct. Southerners, some of them, still issue the occasional rebel yelp that states’ rights and not slavery caused the Civil War. Heedless of improvements in medical and dental care, they yearn for the “Old South.” At 83, I am old enough to assure you that romanticizing the so-called Old South was once a widespread delusion. In 1939, Gone with the Wind — as fine an example of visual and narrative filmmaking as you’ll ever see, opened its title sequence with 63 words of dreamy Old South drivel:

There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields

called the Old South . . .

Here in this pretty world Gallantry took its last bow . . .

here was the last ever to be seen of

Knights and their Ladies Fair,

of Masters and of Slave . . .

Look for it only in books, for it is

no more than a dream remembered.

a Civilization gone with the wind . . .

Those words were not in the book. I know because — upset at the idea of Gone with the Wind being canceled like a cheap stamp — I re-read the book this year. As does the movie, the book falls well short of being a lens of nostalgia. Its pages describe an unending cortege of calamity featuring a group of persons who are, with few exceptions, not worth the cattle prod it would take to get them off your property. The movie carries out the same mission. Whichever of the film’s writers wrote that dreck did Gone with the Wind a dreadful disservice. Moviegoers see that and expect a loving, caressing look at the Old South. That’s not what they get.

The first reviews of the movie Gone with the Wind appeared in December of 1939 and were overwhelmingly positive. Most, including the New York Times, found the movie a faithful reflection of the novel. Times critic Frank Nugent wrote: “Through stunning design, costume and peopling, [Selznick’s] film has skillfully and absorbingly recreated Miss Mitchell’s mural of the South in that bitter decade when secession, civil war and reconstruction ripped wide the graceful fabric of the plantation age and confronted the men and women who had adorned it with the stern alternative of meeting the new era or dying with the old.”

Nugent gives Hattie McDaniel’s portrayal of Mammy a silver medal for acting excellence but tsk-tsked one of her scenes. He wrote, “Best of all, perhaps, next to Miss Leigh [Scarlett O’Hara], is Hattie McDaniel’s Mammy, who must be personally absolved of responsibility for that most ‘unfittin’ scene in which she scolds Scarlett from an upstairs window. She played even that one right, however wrong it was.” The Times of 1940 viewed a pampered white girl being corrected by a African American domestic as “unfittin’.”

Nugent also lamented the rending of “. . . the graceful fabric of the plantation age.”

Gone with the Wind begins in April 1861, around the time of Fort Sumter’s evacuation. Of its four principals — Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh), Rhett Butler (Clark Gable), Melanie Wilkes (Olivia de Havilland), and Ashley Wilkes (Leslie Howard) — not one is an acceptable role model.

Melanie Wilkes comes close. She is unselfish, gracious, generous to a fault, loyal, and too stupid to see that her husband, Ashley, yearns to go a-dultering — and that Scarlett is hell-bent on helping him. Rhett Butler is charming and shrewd but got thrown out of West Point, becomes a war profiteer, frequents bordellos, gambles, and tolerates the Klan. That’s just in the movie; in the book he’s worse. Ashley Wilkes, who would have understood Jimmy Carter’s lust-in-the-heart disability, gets shot at a Klan meeting but never takes his shot at green-eyed Scarlett O’Hara, the book’s protagonist. Scarlett, once you get past her scheming, selfishness, calculated promiscuity, Scrooge-level avarice, and heartless vamping of both another woman’s husband and her sister’s fiancé — after marrying Melanie’s brother in a spell of spite — she emerges as a lovely Southern belle. One that should have been drowned at birth. These are not people you want joining your club or showing up at your family reunion.

The supporting players are nearly as hapless. Gerald O’Hara (Thomas Mitchell) is a hard-drinking, hard-riding Irish plantation owner who invests heavily in Confederate bonds and leaves his heirs and assigns wallowing in poverty. He becomes mentally challenged and dies by falling off his horse and snapping his neck. Ellen O’Hara, his wife, is the embodiment of “Ole Miss,” the woman who is the brains and the visiting angel of Tara, the O’Hara plantation. So intent on aiding the sick is Ellen that she catches typhoid fever from the overseer’s girl friend, Emmy Slattery, and dies from it. The overseer, Jonas Wilkerson, played with smarmy menace by Victor Jory, gets fired, goes to a seminar on carpetbagging, and tries to snatch Tara at a tax sale.

Hattie McDaniel (Mammy) falls between these two groups but should have been listed as a principal. She turned in a superlative performance. Most other African American cast members fare poorly. Butterfly McQueen (Prissy) and Oscar Polk (Pork) define “cringe worthy.” Eddie “Rochester” Anderson (Uncle Peter) comes close. Everett Brown (Big Sam) as Tara’s African American foreman essays a simple dignity but commits the sin of displaying affection for his erstwhile owners — anathema to the cancel crowd. In one of the movie’s few acts of unselfish courage, Big Sam saves Scarlett from an attack by some brutish (white) down-and-outers.

Is this the stuff of romance and nostalgia? Not from my seat in the theater. The parade of disasters is unceasing. Rebel hotheads at the Wilkes barbecue deride Rhett Butler when he points out that the South has no cannon factories. Most of them learn the hard way that Rhett was right. The Confederacy loses the war. Scarlett’s first and second husbands die, one (Melanie’s brother, Charles Hamilton) from measles and pneumonia in the early weeks of his enlistment and the other (Frank Kennedy, once her sister’s fiancé) at a Klan meeting. Rhett Butler, Scarlett’s third husband, watches their only child, Bonnie Blue, break her neck learning to jump her pony. (In the novel. Scarlett had one child by each of three husbands, but scriptwriters excised the first two. Rhett had a son who suffered the same erasure.)

No examination of Gone with the Wind is complete without giving mention to Belle Watling (Ona Munson). Madam Belle’s place is Rhett’s go-to haven of relaxation, and she not only has the requisite heart of gold, she has pockets full of the mineral as well. Belle contributes generously to the germ-plagued Atlanta hospital where Scarlett works as a nurse. Sad trainloads of maimed Rebel soldiers arrive daily at this hellhole.

The careful reader will by now realize that nothing good happens to these people. Scarlett’s parents, one daughter, and two of her three sisters, all die. Half the men in Tara’s Clayton County perish in the war. Bloody, writhing casualties carpet Atlanta’s Peachtree Street. Cotton crops are lost. Taxes soar. Land is foreclosed on. Yankees burn houses and barns, and they take and eat the livestock. Scarlett murders one of them and gets away with it. Major Ashley Wilkes loses his horse in his last battle and has to walk home from Virginia. He ends up running Scarlett’s sawmill and gets caught in a fruitless embrace with her. Melanie dies. The South becomes an occupied country. Rhett is jailed. The slaves decamp, leaving many whites wondering how a churn works.

For the tragically nostalgic, the movie does offer two Old South moments, both early in the film. One is the Wilkes family barbecue where a bunch of dressed-up white folks wander about the grounds of the Wilkes plantation, Twelve Oaks, in the sweltering Georgia sun. The other is a fund-raising ball where Scarlett dances in widow’s weeds as she leads the Virginia Reel with a dashing Captain Rhett Butler — already flourishing as a blockade runner and profiteer. That was it for gilding the Confederate lily. Not one frame shows us a battle featuring heroic Confederates. Overwhelmingly Gone with the Wind delivers a Technicolor sermon on divine retribution. Yet the Hollywood Taliban seeks to remove Gone with the Wind from the screen.

To this day, adjusted for inflation, no movie has earned more money. As a movie it is a priceless commodity. I would argue, however, that the one irrefutable reason for Gone with the Wind’s continuing presence is Hattie McDaniel. Her performance reduces 90 percent of her fellow cast members to background noise. She portrays a servant, but does so with such power, intelligence, morality, humor, and fearlessness that she bested her co-star Olivia de Havilland to win the Academy Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role, the first African-American to win an Oscar.

McDaniel overcame insults that in today’s world, even with the death by repetition of the word racism, seem inexcusable if not unbelievable. The movie’s premiere in Atlanta drew an estimated 300,000 Georgians into the streets, but in segregated Atlanta Hattie McDaniel got no welcome. Her friend, Clark Gable, announced that he would not attend the premiere if McDaniel could not. She convinced him to go.

Most Americans forget that segregation in 1940 was hardly confined to Georgia and the South. The Motion Picture Academy held its 1940 awards dinner in Los Angeles at the Ambassador Hotel’s Coconut Grove nightclub. Hattie McDaniel attended with her escort and her (white) agent but did not sit at the table with Selznick, Gable, and the others. Her party sat at a small table by themselves. To bend even that far, the Ambassador waived its longstanding policy of barring African Americans. But she accepted her Oscar at the dais, delivered a graceful speech in which she expressed the hope that she would always be a credit to her race and to the motion picture industry, and took home her award. The movie took home everything but the table decorations.

So if you want to look at anything about Gone with the Wind through a lens of nostalgia, point your spyglass at Hattie McDaniel. She earned her Oscar fairly and squarely at a time in history when it seemed an unlikely if not impossible achievement. A Kansan by birth, she had to learn Southern inflection for Gone with the Wind. Hattie McDaniel, surprisingly to some observers, believed that stereotypes could be overcome. In a 1947 article in the Hollywood Reporter she wrote: “Several times I have persuaded directors to remove dialect from modern pictures. They readily agreed to the suggestion. I have been told that I have kept alive the stereotype of the Negro servant in the minds of theatre-goers [sic]. I believe my critics think the public more naïve than it actually is . . . Arthur Treacher is indelibly stamped as a Hollywood butler, but I am sure no one would go to his home and expect him to meet them at the door with a napkin across his arm.”

McDaniel never apologized for any role she played, including an estimated 74 portrayals of maids. She was famous for saying “I’d rather play a maid for seven hundred dollars a week than be one for seven dollars a week.”

She died from breast cancer at 57 in 1952. Three thousand attended her funeral, and more than 100 cars accompanied her procession to Angelus Rosedale cemetery. She had asked to be buried at Hollywood Memorial Park (now Hollywood Forever), but it did not accept African Americans. Forty-seven years later, in 1999, Hollywood Forever management erected a cenotaph honoring Hattie McDaniel. In 2021, Gone with the Wind continues to bring “Mammy’s” criticism of “Miss Scarlett’s” manners, dress, and eating habits to a new generation of viewers.

The film is a mainstay of American cinema history. You remember history; it’s one of the things we’re supposed to learn from.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is a very thought provoking article on a film that will always stay the same, the more things change in perception and understanding of racial inequality and the Civil War. I don’t believe the film should be altered or censored. There’s nothing wrong with a disclaimer at the beginning taking falsehoods into account that were not seen as such, in 1939.

It also, being a film, included things it maybe shouldn’t have, and left things out that should have been included. As an extremely expensive film to have produced, many decisions are based on what will draw viewers in to see the film (hopefully more than once) and walk the fine line of being reasonably truthful, but not enough to upset the viewing public.

The film industry, like the auto industry, is in the business of making money with the products produced only being the means to that end. ‘Gone With The Wind’ will likely be viewed differently in the years to come. Some things that are hot buttons now may become hotter still, or subside to a degree with other aspects previously not called into question on the hot seat. Only time will tell which will occur, or not. One thing’s for certain, interest and examination of the the film may die down at certain times, only to return with a vengeance.