Americans looking to bankroll adventures in the early 20th century had to get creative. Expeditions were not cheap, and even wealthy individuals needed financial assistance to pay for equipment and crews. But two notable explorers got especially imaginative by relying on an early version of crowdfunding that piggybacked on a budding American craze: collecting stamps.

Antarctic explorer Navy Rear Admiral Richard Byrd and transatlantic pilot Amelia Earhart made thousands for their journeys by selling postmarked souvenir envelopes and stamps that commemorated their travels. They were helped along by “Stamp-Collector-in-Chief” President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a devoted philatelist who made supporting American exploration as easy as buying a stamp.

Stamp collecting began almost as soon as stamps began being printed in the 1840s. Great Britain first came up with the concept of stamps to solve a postal problem: Mail recipients generally paid postage upon delivery, but their correspondents were skirting the system by writing messages on the outside of mailed envelopes — “Arrived in London” — so that the recipients could then decline to pay the postage. Stamps flipped the script by forcing the sender to prepay for transporting a letter. In turn, the stamp-based system ushered in a revolution. Not only were postal authorities guaranteed payment, but the cost of sending letters fell.

With costs reduced, the number of letters circulating through the mail skyrocketed. Other nations began to adopt Britain’s postal model, too, printing stamps with unique images that represented their nation or empire. With the emergence of beautiful and innovative postage designs, increasing numbers of people naturally started collecting them. Enthusiasts purchased stamps, placed them into albums, and traded them with friends.

Thousands of stamp collectors emerged in the U.S., for instance, where early stamps featured portraits of the first president, George Washington, and the first postmaster general, Benjamin Franklin. The phenomenon of stamp collecting coincided and was bolstered by an emerging network of male-only collecting clubs in the late 1880s that were similar to fraternal orders and dinner clubs. Stamp enthusiasts who did not or could not belong to the collecting clubs could still take part by reading a growing number of stamp-collecting publications. There was no shortage in stamps to marvel over; between 1864 and 1906, collectors printed and circulated more than 900 stamp papers, as they were referred to at the time, in the U.S. alone.

By the 1930s, stamp collecting was so popular that radio stations across the U.S. dedicated broadcasts to newly issued stamps and provided tips for caring for collections. Teachers gave grade school students stamps from around the globe to teach geography. Articles appeared in magazines, such as Ladies’ Home Journal, and large daily newspapers, such as the Washington Post, extolling the virtues of stamp collecting (or, on the flip side, framing it more negatively, as a “mania”). Meanwhile, cultural institutions — libraries, museums, and the like — hosted stamp exhibitions. Even businesses got in on the trend, using stamps to attract customers. Starting in the 1880s, the tobacco company W. Duke and Sons, which already handed out baseball cards in cigarette boxes to attract customers and increase sales, began giving away international postage stamps. The company even printed its own stamp album, which was designed to hold the entire set of stamps distributed in its packages.

Postal agencies took notice and stoked the hobby further. In 1893, Postmaster General John Wanamaker, founder of Wanamaker’s Department Store in Philadelphia, oversaw the issuing of the first commemorative stamp series, a collection of 16 intricately designed stamps depicting the life of Christopher Columbus, to promote the World’s Columbian Exposition. Stamp sales increased by millions of dollars. Between 1893 and 1919 alone, the post office printed 47 more sets of commemorative stamps, most of which celebrated World’s Fairs held in the U.S. From 1920 to 1940, the post office more than tripled its output, printing 150 more, available for a limited time and designed to be collected. Because federal rules restricted American stamps from carrying the image of a living person, most of these designs looked backward to celebrate contemporary events.

It’s hard to say who came up with the idea of tapping into the stamp-collecting craze to raise money for expeditions, but Amelia Earhart was almost certainly one of the first to do so. The famed aviatrix made her name in the early days of flight in the 1920s as one of America’s first pilots, and by 1932 had become the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. Earhart’s trips were expensive, and despite her fame, she was always short on funding.

Earhart’s husband and publicist, George Palmer Putnam, had encouraged her to write an autobiography and go on speaking tours to promote her career, and he also appears to have come up with the idea of helping her make money from the stamp-collecting craze. In 1932, Earhart carried 50 letters she had postmarked and signed on her first solo transatlantic flight. Putnam sold these letters to collectors who sought materials from notable figures. The scheme was successful, and Earhart began carrying mail on all of her international flights.

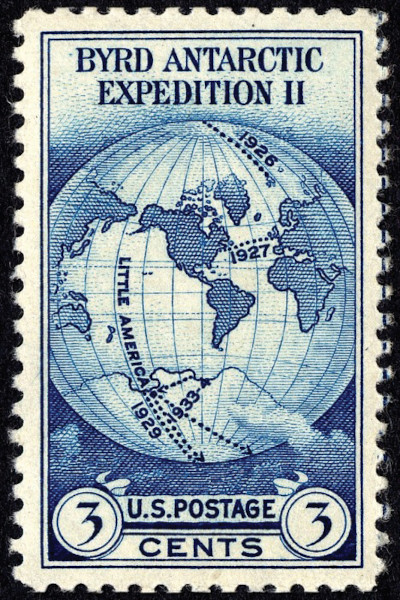

Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd followed her lead. Byrd was a naval scientist who explored the North and South Poles, and he, too, had to raise money for his expeditions. Preparing for a second voyage to Antarctica in 1933, he got the CBS radio network to feature a weekly broadcast from the “Little America” military base in Antarctica, sponsored by General Foods, which also published and sold the “Authorized Map” of the expedition. Like Earhart, Byrd benefited from a fundraising opportunity directed at philatelists. Unlike Earhart, Byrd got government help making it happen, from none other than President Roosevelt.

As a child, Roosevelt learned philately from his mother. In adulthood, he returned to the hobby while traveling the world as assistant secretary of the Navy from 1913 to 1920, and found comfort in his collection after his polio diagnosis in 1921. Newspapers reported that Roosevelt sorted stamps in the White House during his famous first 100 days in office to help him relax while he waited for Congress to vote on legislation.

FDR used his position to encourage stamp collecting and influence stamp production. He submitted ideas for stamps that promoted federal programs, like the national parks, and New Deal initiatives, such as the National Recovery Act.

When Byrd visited Roosevelt in the White House in 1933 seeking financial assistance for his Antarctic expedition, Roosevelt had a brainstorm. Rather than offer government funds, he asked Byrd to send him a letter postmarked from “Little America” — and suggested that other collectors might want a unique souvenir cover canceled at Little America, too, or might be interested in supporting Byrd’s expedition by purchasing a limited-issue stamp. Roosevelt himself sketched out a quick design that was later adapted by artists at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing: a map of the globe with dotted lines pointing out Byrd’s major expeditions to the North and South Poles. Collectors could buy a three-cent stamp, or pay 53 cents for a stamped envelope at Gimbels Department Store or through the U.S. Post Office Department’s own stamp store, the Philatelic Agency.

The initiative was a success. Ultimately, more than 150,000 envelopes were sent down to the “most southerly post office” at Little America, where each piece of mail was canceled with a special seal. Because of the distance carried, the postal service imposed a 50-cent transportation fee, which helped finance the expedition’s expenses, raising approximately $75,000.

While Earhart never got to benefit from the presidential friendship and support that Byrd enjoyed, as her fame grew, so did her connections with American philatelists. She took to carrying hundreds of letters with her on each of her flights, which her husband sold on her behalf. She was also a collector herself and exhibited international stamps, postmarks, and signed envelopes at an international philatelic exhibition in 1936.

Prior to Earhart’s 1937 attempt to circumnavigate the globe, stamp collectors and fans purchased more than 5,000 souvenir envelopes at Gimbels for $5 each. Earhart carried this extra cargo with her, intending to postmark the envelopes at a few stops along her global adventure.

It would be her last. After flying 22,000 miles, Earhart, her navigator Fred Noonan, and her plane disappeared in the South Pacific, carrying $25,000 worth of philatelic cargo. Roosevelt allocated federal resources to a large-scale search to find them, led by Navy and Coast Guard ships.

The plane and pilots, and the thousands of stamped envelopes they carried, were never recovered.

Sheila A. Brennan is an independent historian and the author of Stamping American Memory. This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Arizona State University, produced by Zócalo Public Square.

Originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square.

This article is featured in the January/February 2022 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Very special delivery: Amelia Earhart carried this letter on her flight from L.A. to Mexico City on April 19, 1935, and then took it back to Newark, New Jersey, on a nonstop flight on May 8-9, 1935. The letter is addressed to her husband and adorned with U.S. and Mexican stamps. Note the famous flier’s signature in the upper-left corner. (National Postage Museum)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now