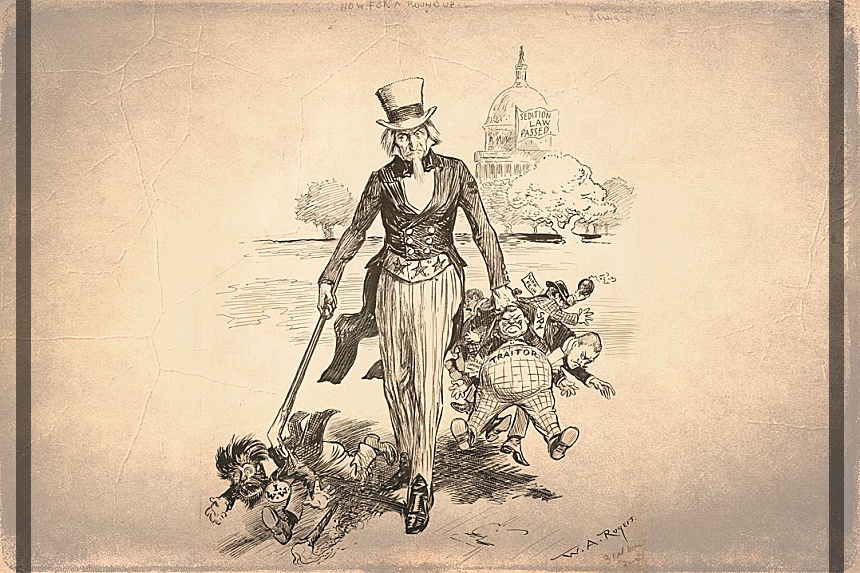

1. Treason, Sedition, and Insurrection: What’s the Difference?

By Jeff Nilsson

Since the events at the Capitol on January 6, there has been a lot of discussion of the terms sedition, insurrection, and treason. But what are the legal definitions of these three acts, and how are they different from one another?

2. Five Items That Have Outlived Their Usefulness

By Troy Brownfield

Some things have stuck around way past their “use by” date.

3. Senior Stoners

By Nicholas Loud

Marijuana was a cornerstone of the youth counterculture of the ’60s and ’70s. Today, with increasing legalization, it ain’t just for kids anymore.

4. A Doctor’s Surprising Findings on Near-Death Experiences

By Bruce Greyson, M.D.

“Suddenly, I realized I was up near the ceiling, looking down at my body. A brilliant white light embraced and encompassed me.”

5. Health Advice for 50-Year-Olds from 100 Years Ago

By Nicholas Gilmore

Consider all that you eat in a day, and halve that. Drink coffee-flavored water. Stretch naked.

6. The Rise and Fall of Saturday Morning Cartoons

By Charles Moss

For almost four decades, watching Saturday morning cartoons was a beloved ritual for millions of American kids. So, why were they so controversial?

7. The Very First Rock and Roll Song

By Troy Brownfield

Experts still debate what the first one was, but the most likely candidate was recorded 70 years ago this week.

8. Who, Exactly, Is the ‘Average American’?

By Jeff Nilsson

If you collected all of the results from the census and other data sets, what would the average American look like?

9. Led Zeppelin IV Turns 50

By Troy Brownfield

If any album was ever forged by the hammer of the gods, it was this one.

10. The Forgotten Miracle of the 9/11 Boat Evacuation

By Christina Stanton

On September 11, 2001, hundreds of boats came to the rescue of 500,000 people stranded in Manhattan – the largest sea evacuation in recorded history. One woman tells the story of what she witnessed that day.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now