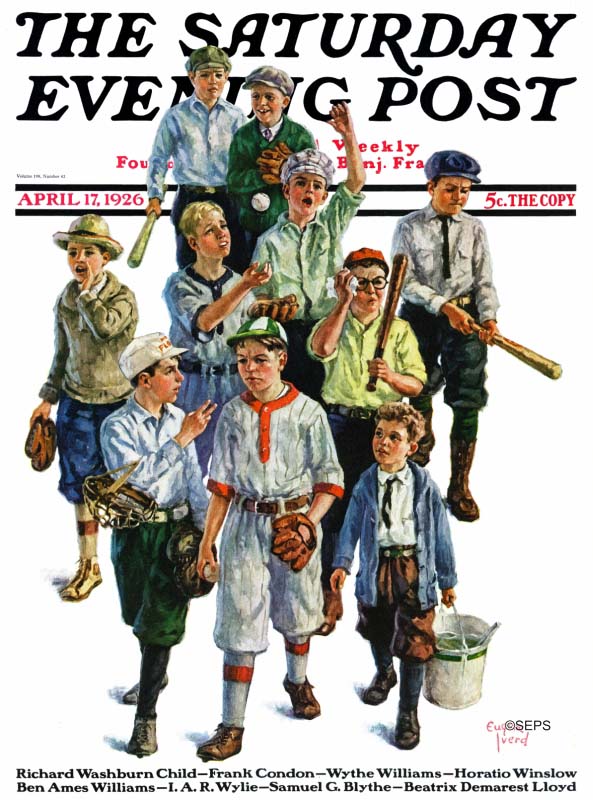

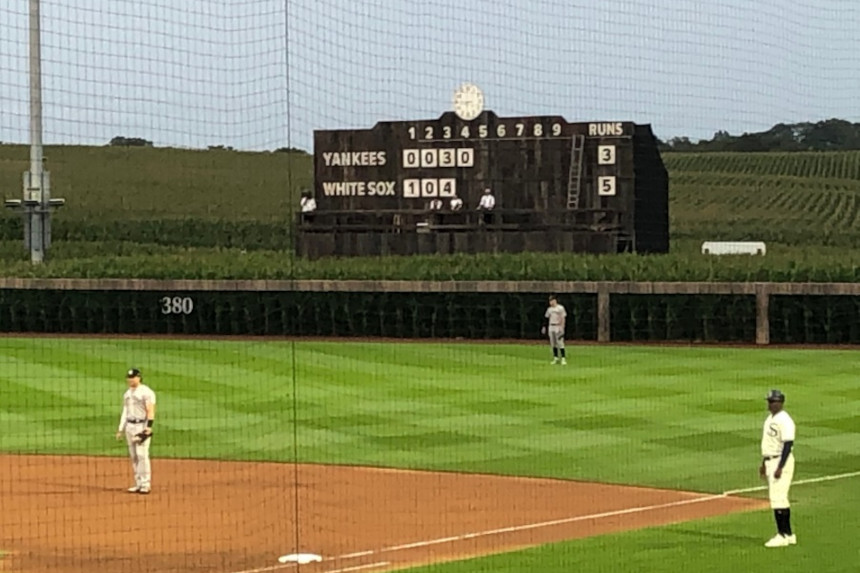

Iowa doesn’t have a Major League Baseball team, but it hosted its first ever game in mid-August with players suited up in jerseys reminiscent of Saturday Evening Post covers in the 1920s, when ballparks had scoreboards made of salvaged barnwood. The Chicago White Sox – New York Yankees Field of Dreams game was postponed from its planned 2020 debut, due to the pandemic. It was played in Dyersville, Iowa, near the original Field of Dreams movie site, and came at a time when people needed to believe in miracles.

Kevin Costner, who portrays Iowa farmer Ray Kinsella in the film based on W.P. Kinsella’s novel, Shoeless Joe, was there. Before the White Sox won the game with Tim Anderson’s two-run homer into the right-field corn, Costner reminded fans that the film which aired 32 years ago, was about unresolved relationships, and perhaps second chances.

In the movie, Kinsella follows the command of a distant voice that tells him to build a ballfield in the middle of his valuable farmland. He risks foreclosure and endures public ridicule. Just as his family begins to think he’s gone mad, “Shoeless” Joe Jackson emerges from the corn with the ghosts of seven other 1919 Black Sox players. Another spirit player is Ray’s father, John Kinsella, a catcher looking wide-eyed and innocent, long before he hung up his cleats to be beaten down by life.

When the estranged father and son unite with a boyish game of catch, viewers see and feel the emotional pull of baseball as the great American constant. The final scene shows miles of headlights approaching the farm, a line of people looking for all that was once good.

One of the most famous scenes in the movie features actor James Earl Jones, now 90, who portrays Terence Mann, a reclusive writer who delivers a thunderous exposition about the constancy of baseball. He says:

The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It’s been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game — it’s a part of our past, Ray. It reminds us of all that once was good, and it could be again.

Ohhhhhhhh, people will come, Ray. People will most definitely come.

Field of Dreams writer/director Phil Alden Robinson agrees with Terence Mann about baseball’s enduring place in America:

I do think that for many people baseball is still a constant, largely because of the role that baseball played in our childhoods. Growing up in the ’50s, playing catch was one of the first two things a boy did with his father that he didn’t do with his mother. (The other thing was learning how to pee standing up). On some elemental level, we understood this was the first step towards becoming a man. There were rules to be learned, skills to be mastered, and idols to emulate. A baseball player was a unique combination of man and boy. They shaved with straight razors, chewed tobacco, and married stewardesses. But they also made their living playing a game, had nicknames (Scooter, Dizzy, Duke), and didn’t wear the grown-up uniform of jackets and ties or work in an office. We wanted to be them.

Among all professional athletes, baseball players were the most relatable. They weren’t giants like basketball players, and they didn’t hide their faces behind masks like football players. Baseball players seemed more like regular guys. You could see yourself in their (spiked) shoes. And you could see yourself winning. Although it’s a team sport, at the heart of baseball is a one-on-one confrontation, pitcher versus batter. Which means that everyone on the team — not just the most gifted athletes, but the weakest players too — had the opportunity to be the hero.

So by the time we’d reach maturity, the word ‘baseball’ meant so much more than just the Major Leagues. It meant minor leagues, semi-pro games, college and high school ball…it meant Little League, and Pop Warner…softball, stickball and stoop ball…and having a catch on a warm summer night.

Surviving ballplayers who threw their first baseball in the 1920s and 1930s, remember when ballfields were literally carved into cow pastures with rocks and manure and tractors parked on the sidelines. In Shoeless Joe’s era, semi-pro players barely had uniforms. Kids played barefooted, sharing gloves, and had to sneak away to play a game on Sunday.

Dodgers pitcher Carl Erskine, 94, fondly remembers those exchanges of catch with his father, who had been a semi-pro player. To improve his pitch, he spent hours throwing a tennis ball into a strike zone drawn with chalk on an old barn door.

As the world continues to change, the Hoosier believes that the game of baseball marks the time. When we last spoke, he said, “I think the beauty of baseball is that it has followed the culture of our times. You can go back and illustrate a lot of things — from stadium lights to the first airplane travel.”

The next Major League match-up at the Field of Dreams ballpark will be in 2022 when the Chicago Cubs face the Cincinnati Reds. Until then, America will roll along like a powerful army of steamrollers, history will be rewritten, and baseball will hold its place as a reminder of what was good and could be good again.

Austin-based writer Anne Raugh Keene is the author of The Cloudbuster Nine: The Untold Story of Ted Williams and the Baseball Team That Helped Win WWII. This essay is part of her work profiling the history of MLB’s oldest-living players. www.annerkeene.com

Featured image: courtesy Willie Steele

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now