—From “I Climbed the Cliffs with the Rangers,” first published in the August 19, 1944, issue of The Saturday Evening Post

We’re off, boys,” cried the sergeant in front of my craft, “and this time it’s really the 49-cent tour!”

By the time we found fairly comfortable positions in the heavily loaded boats, the first glow of dawn began showing in the east. The laughing and joking was still going on, but it stopped abruptly when we saw another craft overturn in the heavy waves just behind us.

As the morning light grew brighter, we could see hundreds of other boats all making for the shores of Normandy. But those boats were landing on beaches, while ahead of us were sheer cliffs that had to be scaled before we could come to grips with the Germans.

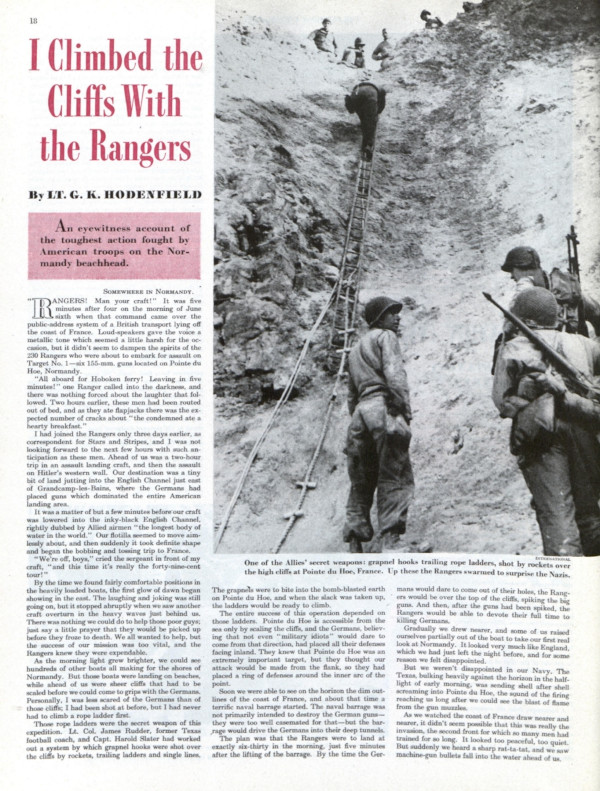

Lt. Col. James Rudder, former Texas football coach, and Capt. Harold Slater had worked out a system by which grapnel hooks were shot over the cliffs by rockets, trailing ladders and single lines. The grapnels were to bite into the bomb-blasted earth on Pointe du Hoc, and when the slack was taken up, the ladders would be ready to climb. The entire success of this operation depended on those ladders. Pointe du Hoc is accessible from the sea only by scaling the cliffs, and the Germans, believing that not even “military idiots” would dare to come from that direction, had placed all their defenses facing inland.

Soon we were able to see on the horizon the dim outlines of the coast of France, and about that time a terrific naval barrage started. The Texas, bulking heavily against the horizon in the half-light of early morning, was sending shell after shell screaming into Pointe du Hoc, the sound of the firing reaching us long after we could see the blast of flame from the gun muzzles.

Snipers and machine gunners were on the cliffs all around us, so we scrambled to the base of the cliff for safety.

The naval barrage stopped, as scheduled, 5 minutes before we were to make our touchdown, but we were far off the course and we had to give up the idea of surprising the Germans.

We kept our heads ducked low below the gunwales of the LCA [landing craft], and we jumped each time a burst of machine-gun fire rattled against our sides. When we dared to look up, we could see men floating around in the water after their boats had been overturned.

I suppose that we all should have been scared when we finally nosed up to the narrow beach to make our touchdown, but we all were too excited. When the nose of our LCA ground against the sand, we stopped; the command was given, and with a loud roar and whooshing sound, our rockets sailed over the top of the cliffs.

The ramp had been lowered and our men were scrambling ashore with lethal weapons ranging from pistols and knives in small hip cases to big bazookas and trench mortars. Snipers and machine gunners were on the cliffs all around us, so we scrambled to the base of the cliff for safety.

Sgt. Bob Youso and Pvt. Alvin White had already started up the ladders which were hugging the face of the cliff, and others were lined up, waiting their turn. My own trip up the ladder was interrupted only by numerous stops to catch my breath. We were able to hear the firing of small arms and loud roars from the top of the cliff, but we had no way of telling what was going on.

Finally I tumbled over the top of the cliff into a shell hole left by a previous bombardment from our air force, and I asked some of the men in the shell hole what the score was. I could learn only that two of the six guns in Target No. 1 had been destroyed by the air force, prior to D-Day, and that the remaining four had been removed by German forces.

Straight ahead of me for a mile was nothing but shell holes. At my left was a series of small fields with hedgerows extending to the cliffs. On the far right was the English Channel.

Other units which were also assaulting the cliffs had been having various sorts of trouble. The Germans had come to the edge of the cliffs and had rolled hand grenades down the ladders. Later, as a sort of afterthought, they started cutting the ropes, but by this time the Rangers had gone up and over and were pushing the Jerries back.

Our men fanned out to destroy the guns, and then, learning that four of them had been removed, two companies formed a big patrol and set out to find them. While this patrol was out searching for our target, other Rangers were fighting snipers and seeking out German machine-gun nests.

This was a new type of warfare, a crazy kind. The Jerries knew every inch of the terrain; they had the place taped right down to the last little shell hole.

There was one machine gun far to our left, but not so far that it wasn’t costing us a number of casualties. Between our line and that machine gun was a field with ACHTUNG! MINEN! signs hung on a fence around it. We knew that there might be mines there — and again, there might not.

Youso and White, the same two men who had been the first ones up the ropes, decided to get that machine gunner, and get him good. They checked their rifles and then started crawling on their stomachs right over that field. Nary a word was said about mines. That was an “occupational hazard” which these men were ready to risk.

They got the machine gunner and they came back, but both had nasty wounds; Youso through the elbow and White through the knee. But neither would leave the line of defense until we all retired at dusk. They both said they could still see Germans and they could still shoot and, anyway, there might be some fun they didn’t want to miss.

As darkness closed in on Pointe du Hoc, our line moved back to form a defensive perimeter around the command post. This post was back of the former German air-raid shelter. Before us, we had a 16-foot concrete wall; in back, we had the English Channel.

Our medic, “Doc,” had found a subterranean chamber nearby with 16 bunks, and here he established a sort of base hospital, where he worked all night with a flickering candle and sometimes a flashlight. At times there were so many patients that men had to lie in the command post until, maybe, one of the other patients would die or could be patched up well enough to go back out.

It wasn’t until late that night that one man returned and reported to Lt. Robert Armand, of Lafayette, Indiana, that the four missing guns had been found and destroyed.

At 1:00 on the morning of June 7, the Germans launched their first counterattack. By daylight the seriousness of our situation really loomed big. The first Jerry attack had been thrown back, but they had regrouped during the night, and this time they penetrated our lines, cutting off a number of our men. Some of them managed to work their way back to our lines, but we lost one officer killed and 19 enlisted men missing in action.

It was about the time of that second counterattack that I gave up hope of getting off Pointe du Hoc alive. No reinforcements in sight, plenty of Germans in front of us, nothing behind us but sheer cliffs and lots of Channel. It is hard to realize now just how short we really were of supplies. Most of our men, in order to carry more ammunition, had left their canteens and rations in the supply boat which was to have followed us in, but that supply boat, it turned out, was one of the first boats sunk.

Our meals generally consisted of D-ration chocolate, biscuits, and cold chopped meat. Doc was in charge of the water distribution, and he gave each of us two-thirds of a canteenful. He didn’t have to say how long it had to last, because that’s all there was.

To ease the ammunition shortage, the Rangers were grabbing all the captured and abandoned German weapons they could lay their hands on. We even had a German machine gun right in front of the command post. Our mortar fire was particularly effective.

But Col. Rudder, cool and calm as ever, was still master of the situation — outwardly at least — although he, too, thought we were goners. He maintained contact with patrols through telephones and he kept constant check on the wounded and on the organization of the defenses.

Lt. James Eiker, signal officer, had established contact with the Navy destroyers just offshore and could call for artillery fire on observed enemy concentrations. His contact was with a signal lamp which he had brought along in spite of protests from his section that their boat already was overloaded. Had he not persisted in bringing that lamp, this story, with a different ending, probably would be written by a German correspondent.

It was about the time of that second counterattack that I gave up hope of getting off Pointe du Hoc alive.

Only that artillery fire poured in by those ships saved our collective necks. Every time the Germans would gather in one spot for attack, Eiker would signal the destroyers and they would blast them with a rain of fire.

The most inspiring sight of that entire second day came when our Navy scared the Jerries out of a house on the road which led down to Grandcamp-les-Bains. I had noticed that house, already partially demolished by previous bombardments, when I first clambered over the top of the cliff. Now I was to see it razed right down to the ground. As the Jerries fled out of it, our Rangers picked them off with rifles.

All that second day we waited for supplies from the Navy, while bitter fighting went on all over our little area. We had complete control of that area, probably 250 yards square, with occasional patrols deeper than that.

Early in the morning the Navy sent a motor whaleboat to evacuate prisoners and wounded, but the boat foundered on the narrow beach. Later on, an LCT tried to come in with supplies but had to turn back because of the strong tide. And then, late in the afternoon — very late, it seemed — two boats made it to the beach, with everything we needed, including one platoon of Rangers for reinforcements.

Doc started making jam sandwiches. Jam sandwiches hereafter will always be sacred with me. They used to be something to eat with a glass of cold milk in the afternoon, but that day they were seven-course dinners, complete with finger bowls.

There were no more counterattacks that night, just patrol activity on both sides. Off to the left, we could see a barrage of flak, as Luftwaffe reconnaissance planes scooted over the main beaches, but the planes didn’t bother us. It was fairly quiet when I lay down to sleep at two in the morning, and it is a commentary on how tired a person can be that I slept soundly for six hours, with a sharp hunk of rock digging into the center of my spine.

This article is featured in the September/October 2021 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: A well-earned rest: Rangers take a breather after scaling the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc and securing a German emplacement. (National Archives)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

They truly were the greatest generation,and stopped evil in it’s tracks worldwide,coming from every nook and corner of America.