Norman Rockwell became famous during the golden age of illustration, when publishers employed thousands of illustrators to meet the insatiable demand for pictures in popular books and magazines.

But starting in the 1960s, the market for illustrators began to fade. First, photography proved to be a cheaper and more efficient substitute for much of illustration. Next, television began to steal audiences from magazines because many readers of illustrated fiction preferred pictures that moved and talked. Then, audiences migrated to the internet. Just as Norman Rockwell’s era had been ushered in by new technologies in reproducing art and printing magazines, it was ushered out again 100 years later by even newer technologies.

So where would all those illustrators find work in the age of the computer?

Many complained bitterly about the impact of computers on art. Mechanized art seemed lifeless and impersonal. Superficial “photo-illustrations” flooded the market. But a small band of pioneers continued to experiment, looking for ways that computers might be used to create art worthy of the old traditions.

One such pioneer was Craig Mullins, who is known today as “the father of digital painting.” You may not have seen his signature, but he helped chart a new path for artists in the alien world of computers, and his artistry can be found throughout pop culture over the last three decades.

When Mullins graduated from art school, he didn’t have a conventional illustration job waiting for him. Instead, he found work designing for theme parks, which led to work in the film industry and eventually to computer video games and other “new media” projects. As he worked with digital images, he played with the tools in his spare time, trying to make pictures that looked authentic, without the heavy fingerprint of a computer.

I recently interviewed Mullins from his home in Hawaii. He remembers, “I experimented during my lunch hour using Photoshop and people said, ‘that’s interesting.’ But nobody saw the potential there. People thought there was a stamp of the tool that could not be escaped. They were wrong. The tool came into its own.”

I asked Mullins what motivated him to step off the computer art assembly line to spend time investigating his own techniques and creating his own digital brushes.

He replied, “When the composer Debussy was studying at the Paris Conservatoire his professors accused him of breaking the rules of harmony. He said, ‘that’s right, I am.’ So they asked him, ‘then what rules do you follow, sir?’ Debussy responded, ‘my own pleasure.’ That was the perfect answer. What you like will never steer you wrong.”

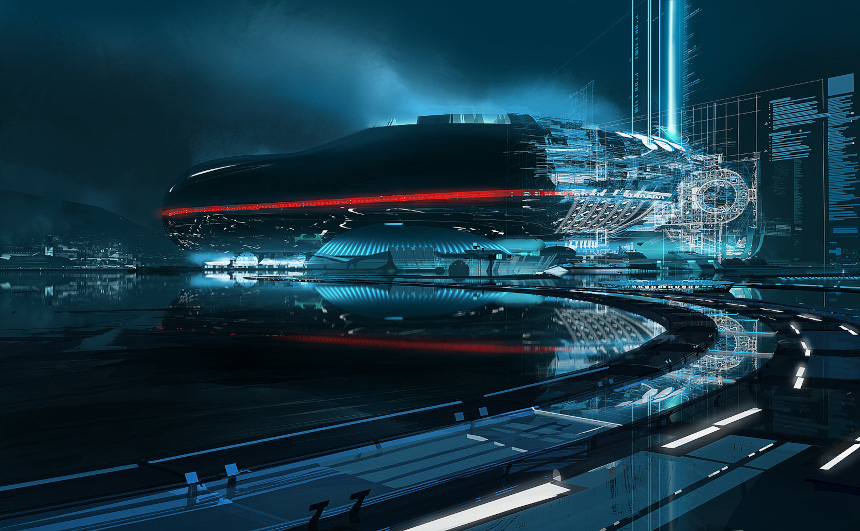

Mullins now has a huge international following as a result of his imaginative work as a concept artist, illustrator, and matte painter. From movies such as Jurassic Park and Forrest Gump to video games such as Age of Empires, Assassin’s Creed, and Halo 2, it turns out that the audience for creative illustration is as large and robust as ever. It has simply evolved from the magazines of the 1940s and ’50s.

In the world of new media, a “conceptual artist” is not just a painter of scenes. A conceptual artist must be capable of building entire worlds of things we’ve never seen before: creatures and characters must be invented in a way that not only looks persuasive, but moves with a gait that makes sense, perhaps in an atmosphere we haven’t previously experienced. Architecture, transportation, landscapes — all must be visualized in a way that coheres and is ergonomically believable. Norman Rockwell never had assignments like that!

One reason that Mullins stands out among other digital artists is his insistence that the human imagination, and not super powerful digital tools, remains at the core of art. He worries, “The more powerful tools become, the more of the artist gets lost.” He does not mind a teaming relationship between an artist and a software engineer, but he does not want to relinquish control to the computer. That’s why he is careful to continue to work in traditional media as well as computers, and to step back from his paid assignments to refresh his skills and his approach.

He tries to emphasize this point to art students who have grown up with computers. He is in constant demand around the world, as people in China, Korea and Europe ask him to come lecture about his techniques. He says, “Students are always looking for answers to questions like ‘how do I duplicate that effect?’ Or ‘show me how to draw a finger.’ They’re asking the wrong kinds of questions and become disappointed when I tell them that there’s no secret to share with them, that they need to draw more.

The importance of fundamentals like good drawing is one area where Mullins and Norman Rockwell would still be in complete agreement. Mullins frets, “there isn’t the insistence on learning to draw that there used to be. You no longer have to learn how to draw. Photoshop allows people to fuss with things forever until they come across something that works right, and if they don’t, they can simply darken the parts they don’t like. As a result, you get bad structure, bad anatomy, rampant abuse of atmospheric perspective, wholesale importation of stock models, and pose stock models.”

Still, Mullins is excited by the future. “It’s been quite a ride and nobody knows where it’s going to go. We just don’t know what will be considered art or what people will find to be of value in in the future.”

Featured image: Image by Craig Mullins (detail) (copyright Craig Mullins)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Excellent new feature, David. Haven’t seen one in some time. I wasn’t familiar with Craig Mullins previously. He seems to see the computer as an aid or assistant to his art, not letting it do the creating and/or calling all the shots.

Speaking of, I’ve been seeing ads for ‘Original AI Art’ online. Their fundamental question is “What happens when you teach an algorithm to paint?” The results appear to be beautiful. The ones depicting past centuries really look like they were painted then, by a human, but they were not.

One of my favorite artists is ‘Futurist’ Syd Mead who passed away in December 2019. You’d think his works were done by computer considering they depict futuristic scenes, but they weren’t. The ‘Tron’ illustration near the top has a Mead look to it; Bob Peak as well. I love the large’Tangled’ at the bottom. I can tell it’s depicting the late 1700’s to early 19th century, definitely not the later sections. Not sure which country. France or Belgium, possibly? Not Spain or Italy. Regardless of that mystery, it’s very captivating.

At the rate things are declining and getting uglier by the day, it seems unlikely they’ll be much appreciation for anything beautiful by the masses (who are asses) in the future. But there will also be the discerning who do.