This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Anniversaries offer one of the clearest ways to both remember the past and consider its legacies in the present, and I’ve often written about many historic anniversaries in this space (including in my most recent column, on a pair of 1921 centennials). But anniversaries can also be profoundly personal, and this week my family will celebrate such a personal occasion, the 51st wedding anniversary of Steve and Ilene Railton, my parents.

The perseverance and optimism required to arrive at a 51st anniversary, and the life and family they’ve created together over that half-century, are some of the many personal lessons I’ve learned from my parents. But both of their lives, identities, and stories have also modeled for me the pair of ideas and American ideals at the heart of my teaching, my last two books, and all my ongoing writing and work: inclusion and critical patriotism.

Many elements of their stories start during their time in college, at the linked Columbia and Barnard Universities (Columbia had not yet gone co-ed) in the late 1960s. Those campuses were epicenters of the decade’s critical patriotic protests and social movements, so much so that much of the Spring 1968 semester (during my parents’ sophomore year) was cancelled due to the extent of protests and campus takeovers. And that activism achieved tangible effects far beyond those cancellations, with Columbia President Grayson Kirk’s resignation and the formation of a University Senate to allow for more communal input moving forward.

It was also sophomore year when my parents began their relationship, a partnership (culminating in their marriage the day after their graduation in June 1970) which illustrated the American ideal of inclusion on multiple levels. For one thing, it was an interfaith relationship, one which initially unnerved both my Mom’s Jewish parents and my Dad’s Southern Baptist mother; it didn’t take long for both families to be thoroughly won over, however, itself an important layer to such inclusive relationships. And for another, related thing, those heritages and family stories featured so many versions of America that came together in this marriage and family: Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who settled in Boston at the turn of the 20th century, where my maternal grandparents met and married; German immigrants to the Midwest who ended up in Missouri, where my paternal grandmother grew up before attending the University of Iowa as a journalism student; Anglo-Canadians who crossed the border and settled in New Hampshire, where my paternal grandfather grew up before likewise ending up at Iowa and meeting his future wife.

After a few years in graduate school in New York, my Dad at Columbia for English and my Mom at Bank Street College of Education for early childhood ed, my Dad got a job at the University of Virginia and my parents moved to the Charlottesville area in 1974. Charlottesville in the 1970s was in many ways still a small Southern town, but one that was undergoing a moment of intense, necessary change. Not long after they moved, my Mom experienced the striking differences between that persistent small town perspective and life in New York City, when a woman stopped her to ask (apparently not unkindly) if she was a gypsy. But this was also the era in which the Charlottesville public schools had been recently, fully integrated; and in 1974, the same year that my parents moved to the area, the city opened the new Charlottesville High School to accommodate that larger, integrated student population.

In that complicated, evolving city and time, both of my parents worked to push Charlottesville’s communities toward critical patriotism and inclusion. My Dad did so through his 46 years of teaching and work at the University of Virginia, a career consistently centered on challenging UVa’s privileged students to better remember the breadth of American history. One telling example was a summer session class on Representations of Race that he created and taught for many years, pushing students to have uncomfortable conversations about literature, pop culture, and race in America that have only become more relevant still in subsequent decades.

My Mom did so through a four-decade career that touched on every side of early childhood education and care in the city, from her early role as the director of the groundbreaking Westminster Child Care Center to her work both licensing day care providers and helping parents and families find such resources for the organization Children, Youth, & Family Services (CYFS; now renamed ReadyKids). I used to joke with my Mom that apparently everyone in town was a day care provider, since every time we went out she would be warmly greeted by multiple folks. But those experiences reflected just how fully her work connected her to the community in inclusive ways, and just how much she touched the lives of so many in Charlottesville (across, for example, the city’s still too-often segregated neighborhoods).

In the final stages of those multi-decade careers, both of my parents expanded and deepened their efforts and effects. My Dad did so through his work on a series of groundbreaking public scholarly websites and digital humanities projects, and most especially through the award-winning Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture site, which countless educators have used to present a fuller picture of that hugely influential American text. My Mom did so through her decade of work as an educator and counselor with the influential and inspiring Bright Stars Program, a Head Start-like preschool program dedicated to providing educational opportunities, resources, and support for the region’s most disadvantaged children and families. Even after retirement, they’ve both extended this work, my Dad through further developing the scholarly websites and my Mom through an evolving creative writing career focused on telling the stories of those children and families.

I was profoundly affected by all those layers to their work, from my time at Westminster Child Care Center and as a student in the Charlottesville Public Schools to so many experiences in their offices at UVa and CYFS. My own Charlottesville story has likewise evolved and continued to influence my perspective and ideas, both as I’ve learned more about the city’s complex histories and as I’ve experienced its fraught 21st century events (my sons and I drove down for our annual summer visit on the same day as the infamous August 2017 Unite the Right rally, for example).

But there’s been no bigger influence on my teaching, my career, and my public American Studies scholarship, including this Considering History column for its three-and-a-half years of existence, than the lessons in inclusion and critical patriotism I received from my parents. For their 51st anniversary, I hope to continue passing on those vital gifts they’ve given me and their communities alike for so long.

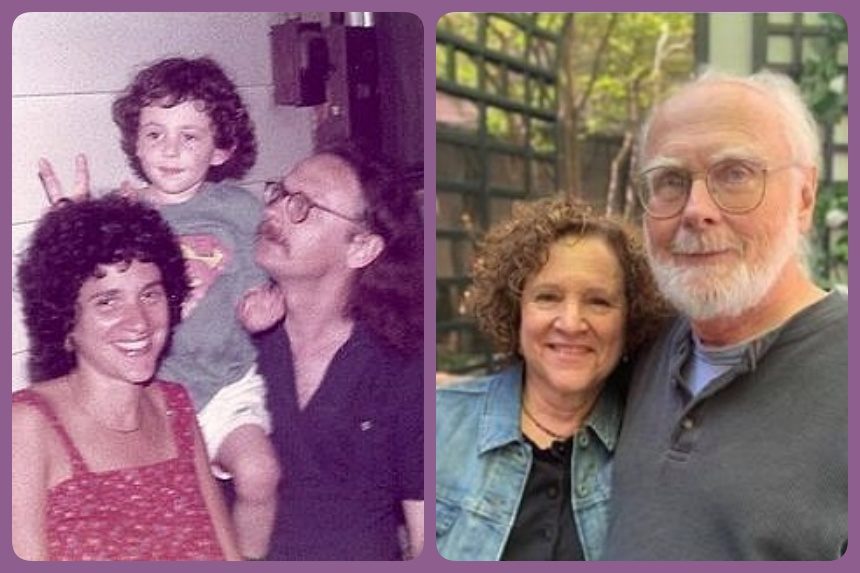

Featured image: Ben Railton’s parents in 1981 and today (courtesy Ben Railton)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks so much, Bob! Agreed on all counts about them, and I very much appreciate the kind words as ever.

Ben

I certainly wish your parents a very happy 51st anniversary! I know that technically we can’t necessarily make any assessments or conclusions about people from photos, but I could tell immediately Ben, that they’re wonderful people. This was before even reading their remarkable story of selfless accomplishments in making this nation a better place.

I looked at the links provided, and am very impressed. If you don’t mind, I might add that you’re one of their greatest accomplishments too in also trying to make America better with all of your writing for this Post site, and books otherwise. Tell your folks to keep their post-retirement work going. They have as much to offer as ever, so why not keep that kite up in the air?!