While U.S. Senators debate how the loss of the filibuster might affect the Senate’s legislative processes and effectiveness, Stephen Colbert has a different take:

I’m concerned that if we get rid of the filibuster, we’ll lose one of our government’s silliest words.

— Stephen Colbert (@StephenAtHome) March 17, 2021

While filibuster does sound like a silly word, it has a history in violence that’s far from funny.

The Dutch had the word vrijbuiter meaning “pirate,” from vrij “free” and buit “booty.” Although its path from Europe to the New World isn’t well documented, a leading theory is that the word was adopted into English as freebooter or fleebooter, which the French turned into flibustier (the s was added but was silent), and the Spanish adopted as filibustero in the late 16th century to describe pirates raiding Spanish colonies in the West Indies.

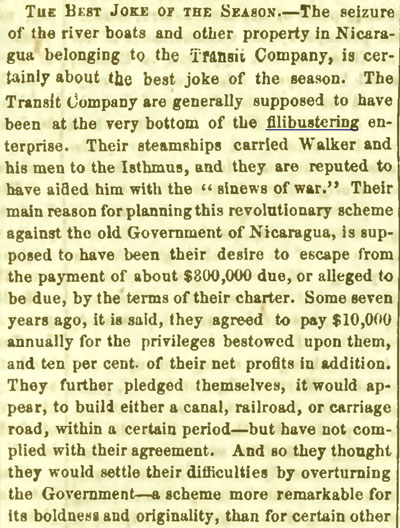

Americans then brought the word back into English as filibuster with a more narrowed meaning: It described mid-19th-century American “adventurers” who engaged in unauthorized coups against Central and South American governments that were otherwise at peace with the United States. William Walker was a filibuster whose successful but short-lived attempt to overthrow the Nicaraguan government in 1856 was often reported on in the Post.

In the 1860s, Senator John Randolph of Virginia was known for giving long and irrelevant speeches on the floor of the Senate — often as a delay tactic. Vice President Calhoun refused to rule him out of order, allowing his speeches to continue.

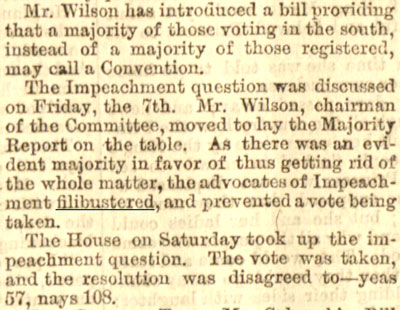

Senate debate rules had permitted such long-winded obstructions for decades (the first actual Senate filibuster occurred in 1837, but it wasn’t called that), but the tactic became more popular in the 1860s. In these times, filibuster — of the government-overthrowing sort — had caught the American imagination, and Senators like Randolph themselves came to be called filibusters, metaphorically comparing their interference with the normal flow of the U.S. government with the interference of William Walker and his ilk with the governments in Central and South America.

Attempts were made to alter debate rules so that a filibuster could be cut off and the work of legislating could continue. However, in 1872, Vice President Schuyler Colfax ruled that “under the practice of the Senate the presiding officer could not restrain a Senator in remarks which the Senator considers pertinent to the pending issue,” and the filibuster was allowed to continue.

Changes to Senate rules were implemented — with bipartisan support — during World War I that allowed a filibuster to be halted if two-thirds of voting Senators agreed to it, a difficult supermajority to achieve in our current 50-50 Senate.

Featured image by William Henry Jackson, taken between 1880 and 1897. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now