Americans take their Christmas decorations seriously.

Be it Danny DeVito and Matthew Broderick’s feud in the holiday movie Deck the Halls or angry New Yorkers criticizing the lackluster 2020 Rockefeller Christmas Tree, people from across the 50 states are clearly passionate about the aesthetics of Christmas. However, this fervor surrounding the grandeur of Christmas trees, ornaments, and lights in the U.S. is not a new development. Instead, the history of Christmas decorations in America tells a long story of religious traditions and modern technologies as they intersected and changed across centuries.

Deck the Halls Official Trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

The story of Christmas decorations begins millennia ago, even before the first Christmas. Green fir trees were first used by pagans during Roman times to celebrate the winter solstice and other seasonal festivals (including Saturnalia, the Roman festival of lights that Christmas day is currently based on). The trees were adorned with natural decorations like pine cones, berries, and nuts, and later with candles and other handmade ornaments. The “modern” Christmas tree first emerged in the 15th or 16th century, when Christians in modern-day Germany adopted the tradition of the tree as a symbol of everlasting life with God. It was during this time that many classic Christmas ornaments first appeared, including the angel at the top of the tree and the classic German bulb-shaped ornament. Interestingly, the first synthetic Christmas trees were also developed at this time, as those who couldn’t afford trees built pyramids of wood, which they decorated with paper, apples, and leaves to mimic the appearance of green firs.

German immigrants brought these practices with them to America in the 18th and 19th centuries. However, the traditions of the Christmas trees, candles, and ornaments were promptly rejected by Puritanical religious groups for their historically pagan connotations. While many foreign-born Americans continued to practice these traditions amongst themselves, it would take an event on the other side of the Atlantic to change many other Americans’ minds.

In the late 1840s, a published depiction of England’s Queen Victoria celebrating Christmas with her German-born husband, Prince Albert, and their family around a decorated evergreen tree circulated throughout the U.S. Queen Victoria was said to be quite taken with German Christmas traditions, and soon enough wealthy Americans — many of whom were intent on replicating the lifestyles of their European counterparts — adopted the practices. Large shipments of German-made ornaments were imported into the U.S., and many American artisans tried their hand at creating decorations. President Franklin Pierce even got in on the action, putting up the first White House Christmas tree in 1856. Yet still, Christmas decorations were not commonplace for all Americans, instead limited to immigrant communities who decorated for tradition and wealthy enclaves who decorated for status.

This all began to change in the late 1800s, thanks not to the whims of European Victorians, but rather American inventors and businessmen. Once electricity was developed by Thomas Edison (or Nikola Tesla depending on whom you ask), industrious Americans sought to use the new technology for a bevy of applications, ranging from the telegram to the electric streetcar. In 1882, Edward Hibberd Johnson — vice president of the Edison Electric Light Company and an inventor in his own right — was living in one of the first “wired” areas of New York City. As Christmas approached, Johnson had the bright idea of replacing the fire-prone candles that he used to decorate his tree with a set of specially made electric bulbs. In the parlor room of his home at 136 East 36th Street, Johnson hand-wired 80 red, white, and blue light bulbs, attached them to a generator, and strung them all around his tree. The tree was visible from the street below, attracting the attention of passersby and eventually the national press. “At the rear of the beautiful parlors, was a large Christmas tree presenting a most picturesque and uncanny aspect,” wrote the Detroit Post and Tribune when describing Johnson’s tree. “It was brilliantly lighted with…eighty lights in all encased in these dainty glass eggs, and about equally divided between white, red and blue….One can hardly imagine anything prettier.”

Like Queen Victoria’s publication before it, news of Johnson’s Christmas-time creation spread throughout the country, inspiring many other Americans to partake in the newly-electrified traditions. In 1895, President Grover Cleveland put up the first electrically lit tree in the White House, and by 1901, Edison Electric was selling nine-socket lighting strips and taking out ads in publications like the Ladies Home Journal. These innovations coincided with the mass production of other Christmas decorations, namely bulb ornaments. By the 1890s, Woolworth’s Department Store was selling $25 million in German-style ornaments, inspiring other American department stores to start producing and selling ornaments themselves. As mass production and electricity became more common throughout the U.S., Christmas decorations became cheaper and more accessible to Americans outside of the wealthy elite.

Christmas decorations were no longer just borrowed traditions from European culture, but rather an American tradition in and of themselves. In 1923, President Calvin Coolidge pushed the button to light the first National Christmas Tree in Washington D.C., a 48-foot balsam fir covered with 2,500 electric bulbs. In 1931, a group of construction workers at Rockefeller Center in New York pooled their money to buy a 20-foot balsam fir and lift their spirits during the Great Depression. In 1933, Rockefeller Center publicists decided to make the Rockefeller Christmas Tree an annual affair, and in 1951 the Rockefeller Tree Lighting was broadcast nationally on NBC. Such traditions continued to grow in popularity throughout the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s, becoming distinctly American symbols of hope and resilience during the depression, World War II, and beyond.

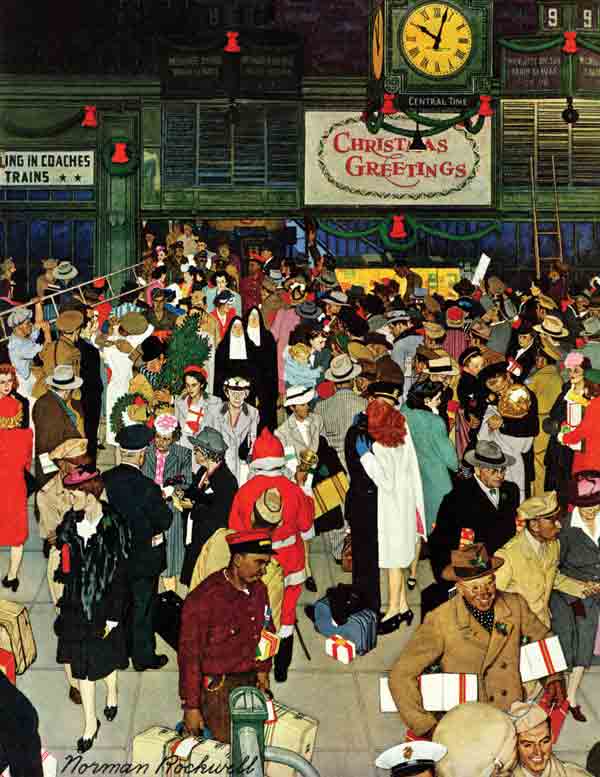

As traditions like the Rockefeller Christmas tree grew in cities, the growth of American suburbs and the baby boom allowed the Christmas decoration bug to spread throughout small towns as well. American home ownership skyrocketed after the Second World War, affording many new Americans the opportunity to display Christmas trees and lights in their own homes. As Christmas illustrations portray (including classic pieces from Norman Rockwell), Christmas decorations were ubiquitous in public spaces as well as private homes by the middle of the 20th century. These Christmas-themed works depict busy train stations and quiet homes alike, all decked out with ornaments, lights, tinsel, and trees.

For Americans, the public and the private aspects of Christmas decorations often intersect. As was the case with Edward Hibberd Johnson back in 1882, Christmas decorations inside the home are often done for the pleasure of people out on the street. This duality has been taken to the extreme in recent decades, with some decorations in private homes just as elaborate and popular as the Rockefeller Center Tree. Take for example the Dyker Heights neighborhood in Brooklyn. Despite being a quiet area near the southern tip of New York City, Dyker Heights now attracts tourists from around the world due to the unbelievably grand decorations displayed in front of some houses. Some residents of the neighborhood offer walking and bus tours for visitors, while other residents believe that the attention — and the decorations — are a bit much.

The Dyker Lights in Brooklyn, New York (Uploaded to YouTube by Curbed)

“There’s no feeling like driving through the neighborhood and seeing all the hard work that people put in to making their homes look great,” said Michael Vazquez, a Dyker Heights local. “The only downside is how busy the streets and sidewalks get, which can be a little concerning given the pandemic. Weekend nights there’s always a lot of traffic but not a lot of parking.”

Although Dyker Heights is an extreme example, the national statistics regarding Christmas decorations show just how widespread the tradition is in the U.S. According to Business Insider, it’s estimated that Americans spend more than $6 billion annually on Christmas decorations. More than 80 million homes decorate and over 150 million strands of lights are sold each year. In 2013, ABC even started hosting The Great Christmas Light Fight, a game show that offers cash prizes to contestants for competitive Christmas decorating.

The Field Family’s Disney Parks Display from The Great Christmas Light Fight (Uploaded to YouTube by ABC)

Christmas decorations have a contradictory history in America. On one hand, they originated in private homes, bringing comfort to German immigrants familiar with the traditions and other Americans who found peace, hope, and joy through them during the holiday season. On the other hand, Christmas decorations have always been designed to garner the public’s attention, be it from wealthy urbanites trying to emulate Victorian culture or modern families hoping to show off the newest and brightest lights technology has to offer. Perhaps it is these unique dualities that make Americans so passionate about their decorations.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

What a fascinating look at the evolution of Christmas decorations in America! I loved learning about how traditions have changed over the decades. The shift from homemade to commercial decorations really highlights how society has influenced holiday celebrations. Can’t wait to decorate my own tree now with a newfound appreciation for the history behind it!

Fascinating dive into the rich history of Christmas decorations in America! As we cherish these traditions, it’s also crucial to maintain a cozy and healthy home environment during the festive season. Professional air duct cleaning services ensure a clean, fresh atmosphere, perfect for showcasing those beautiful decorations. Thanks for the enlightening journey through Christmas décor history!