If he is remembered, the journalist and radio man Walter Winchell evokes a few different types of memories. Baby boomers might recall the narrator of the 1959 series The Untouchables. Their children might have caught the HBO biopic Winchell that starred Stanley Tucci as the fedora-donning gossip columnist. Younger people likely won’t recognize the name Walter Winchell at all. But consider this: every time you guiltily click on a link promising a juicy scoop on a washed-up actor, Winchell is somewhere, smiling.

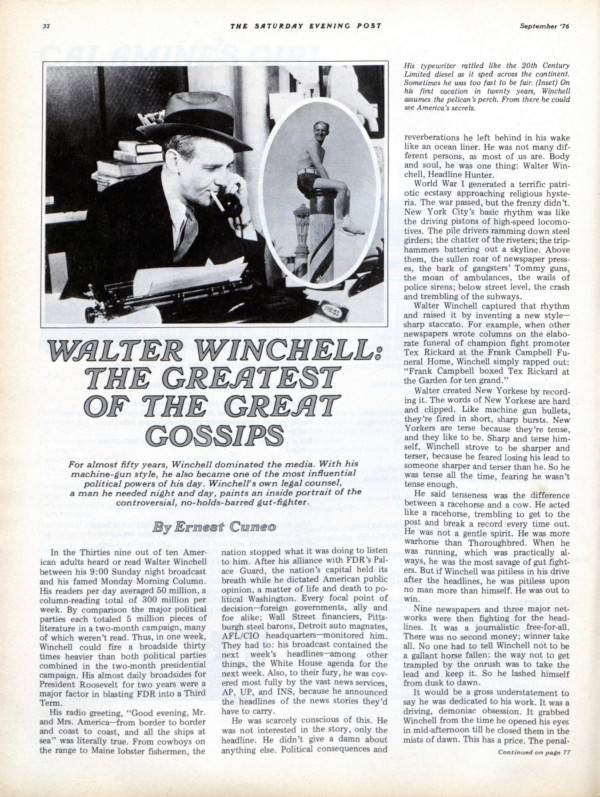

In his heyday, Winchell commanded a collective audience of about 50 million Americans — two-thirds of the adult population in the 1930s. As biographer Neal Gabler claims in American Heritage magazine, anyone walking the streets on a warm Sunday evening in any city in America at the time would hear Winchell’s staccato voice through successive open windows on their way, giving updates on the war in Europe or a famous couple who might be “infanticipating.”

Making and breaking celebrities and politicians in his syndicated columns and radio broadcasts, Winchell built a complicated legacy. Though he often leveraged his platform to give a voice to everyday Americans, Winchell’s lifelong quest for popularity became his own undoing.

A new PBS American Masters documentary, Walter Winchell: The Power of Gossip, offers viewers a new look at how, for better or for worse, Winchell created “infotainment.” The documentary tracks the gadfly’s rise during the Great Depression and his slow decline in the McCarthy era, with Whoopi Goldberg as narrator and Stanley Tucci reprising his role as Winchell.

Director Ben Loeterman says that he was drawn to Winchell’s story as a sort of explanation of the current state of news media: “I think understanding the origins of how news is shaped and delivered and the importance of story, that has become absolutely part of journalism today, started in that sense, I think, with Walter Winchell.”

Winchell’s career arc can be simply understood with his own words: “From my childhood, I knew what I didn’t want: I didn’t want to be cold, I didn’t want to be hungry, homeless, or anonymous.”

In his early years reporting Broadway gossip at Bernarr Macfadden’s New York Evening Graphic (a tabloid commonly called the “Porno-Graphic”), Winchell learned that “the way to become famous fast is to throw a brick at someone who is famous.” He quickly made enemies, namely the Schuberts, who banned him from their theaters. Winchell secured a hefty readership, though, with his euphemistic claims about Jazz Age New Yorkers. Soon enough, he was rubbing elbows with Ernest Hemingway, Al Capone, and plenty of others who feared and respected his power of the press. He regularly attended Manhattan’s Stork Club, where anyone who was anyone knew to find him.

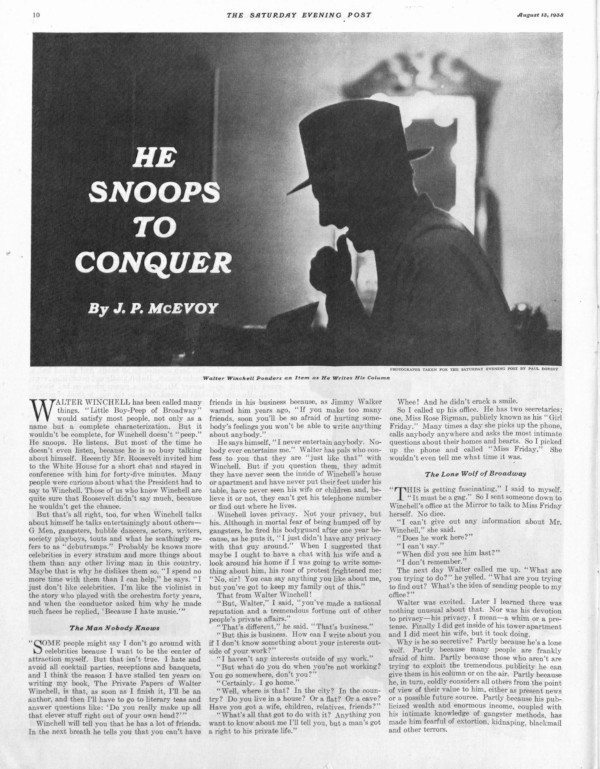

J.P. McEvoy turned a journalistic eye onto Winchell and his brand of “personal journalism,” writing the profile “He Snoops to Conquer” in this magazine in 1938. “Because he was fearless, talented, tireless and tormented by an unappeasable itch for success,” McEvoy wrote, “he arrived at his present peak — where he lives in a state of ingenuous surprise that he has arrived and a gnawing fear that he cannot remain.” Winchell was making about $300,000 a year at the time, between movies, radio, and his column at the Daily Mirror, which was syndicated to thousands of papers across the country. He had become famous for, among other things, coining provocative slang many called “New Yorkese.” H.L. Mencken, in The American Language, noted Winchell’s introduction of several words and phrases into the lexicon. Reno-vated (divorced), obnoxicated, Hard Times Square, intelligentleman. A young couple might be cupiding or “makin’ whoopee.”

Winchell’s reports weren’t limited to celebrity gossip, though. He was an early, outspoken critic of Nazism, taking shots at Hitler as a “homosexualist” called “Adele Hitler” (“he put a hand on a Hipler … ”) and regularly blasting antisemitic Nazi propaganda. When a German-American man named Fritz Kuhn began rallying Nazi sympathizers, first in the Friends of New Germany and later in the German-American Bund, Winchell found a nearer target for derision (“the SHAMerican”). Kuhn thought of himself as a sort of “American Führer,” organizing youth camps and rallies with the growing Bund in the ’30s. Right before more than 20,000 Nazis and Nazi sympathizers descended on Madison Square Garden in 1939 for George Washington’s birthday, Winchell tore into “the Ratzis … claiming G.W. to be the nation’s first Fritz Kuhn … There must be some mistake. Don’t they mean Benedict Arnold?” Winchell was delighted when Kuhn was sentenced to prison for embezzlement that year, writing about how the warden would be “the chief sufferer.”

At the start of President Roosevelt’s first term, Winchell praised the president as “the nation’s new hero,” sparking a close relationship with the administration that would prove fruitful for both of them. Years later, Post editor and former Roosevelt liaison Ernest Cuneo wrote all about how prominently Winchell had figured into their strategy to get FDR a third term (“Look, Walter,” I wanted to say, “you are the Third Term campaign.”).

Winchell was taken with President Roosevelt — and perfectly happy to act as a patriotic mouthpiece for the New Deal and American intervention in the war — but after Roosevelt left office, the gossip reporter found himself politically stranded. In 1951, Winchell affronted African-American performer Josephine Baker when he failed to defend her allegations of racism at his beloved Stork Club. Then, in 1954, he frustrated public health efforts by incorrectly announcing on his broadcast that a new polio immunization “may be a killer,” contributing to a dangerous anti-vaccination backlash. Winchell was really sunk, however, after he aligned himself closely with Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn.

“If he thought there was a star he could hitch himself to,” Loeterman says, “that was more important than the politics or any of the rest of it.”

Winchell transferred his disdain for Nazism into the anti-Communist witch hunts of the ’50s. He had vocalized his opposition to communism throughout his career, but McCarthy and Cohn made him an honorary member of a new — doomed — club. As Gabler put it, “he would lose because his populism had transmogrified into something cruel and unmanageable, just as his detractors had charged. Once a lovable rogue, Walter Winchell had become detestable.” He had brief stints on television in the ’50s, but nothing stuck. Winchell’s newspaper and radio routines were things of the past, and he had cultivated too much public distrust.

Although he faded from the public eye, Winchell’s mark was already made: the “welding” of news and entertainment. Two years after his death, People magazine was launched, and no shortage of commentators and gossips have haunted our screens and papers since. Kurt Andersen wrote in the Times about the evolution of Winchell’s personal journalism, “As star columnists leveraged their columns to accumulate personal celebrity and their personal celebrity to generate more readers, the market for their sort of journalism grew.”

If Winchell isn’t remembered, then he ought to be, if only so that we can more clearly understand that clickbait has a snappy, five-foot-seven predecessor who was one of the most famous men of his time.

Featured image taken by Paul Dorsey, The Saturday Evening Post, August 13, 1938

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Michael Herr, the narrator of the movie “Apocalypse Now” (the basis for some of which was Herr’s Vietnam reportage, “Dispatches”), wrote a short novel about Walter Winchell. I read it some years back. As “a Boomer,” I remember that staccato Winchell narration of “The Untouchables”: “On December 23d, 1932 …”

Interestingly, another gossip-, intrigue-, publicity-obsessed guy that hitched his star to Roy Cohn was a Winchell caricature, Donald Trump.

Fascinating article on a man who’s earthquake he put into motion shakes even more strongly than ever, almost 5 decades after his death. People magazine has been around for so long now most don’t even know it was started by the publishers of the weekly LIFE (1936-’72) after it folded due to economic unsustainability. It took the people/human interest aspects of LIFE that were retainable, and made a plainer, no-frills version of it so to speak.

The publishers were very conscious the public saw it as the void to fill the gap left by LIFE and that it would not be seen as a gossip rag of low degree. Until the early ’90s it was pretty faithful to that ideal. But then the tawdry slowly took over with Amy Fisher, Lorena Bobbitt, Susan Smith then of course the O.J. Simpson saga. By 2000 when a whole slew of even worse bottom feeder competitors came out, that was the end of any resemblance of the original version of People.

There are similar patterns to the highs (then lows) of Walter Winchell’s career. Like the way I tied that together? I watched the excellent PBS special on Winchell before typing this per your link. Thanks for that. It mentions how he wanted/liked the rich to be brought low. I feel the same way about the destructive, undeserving rich of Hollywood crashing and burning due to C-19. Not the majority of ‘worker-bee’ employees trying to make a living.

No, I mean the executives pouring toxic crap into the traditional movie theaters aimed at the masses who are getting along just fine without them. Junk “celebrities” no better looking or talented than any ‘ordinary’ American, no longer being celebrated, and never should have been in the first place. Stripped of a facade never to return. Let Netflix, Hulu, Amazon take their place. Hollywood’s been on the way down for a long time. Corona virus just pushed it from the curb into oncoming traffic. The ratings for awards shows have been plummeting for years. No one wants to hear this or that generic actor/actress’ rambling politics or see ‘who they’re wearing’ on that dirty, worn out red carpet.

Winchell was a mixed bag of good and bad, as so many things are. He was onto Hitler fairly early. I knew about the Hitler youth camps in Germany, but not in the United States. I really hope we’re not on the verge of this again. He deserved getting burned by Josephine Baker getting the NAACP on him. That was one of worst things he did, doing nothing when he was aware of what was going on. She was a true star, and handled it in the right way, keeping her dignity. It was one misfortune after another for Walter between the ’50s and the ’70s, but he set those dominoes into motion long before, knocking each other down, and we’re still living with his consequences, like it or not.