This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

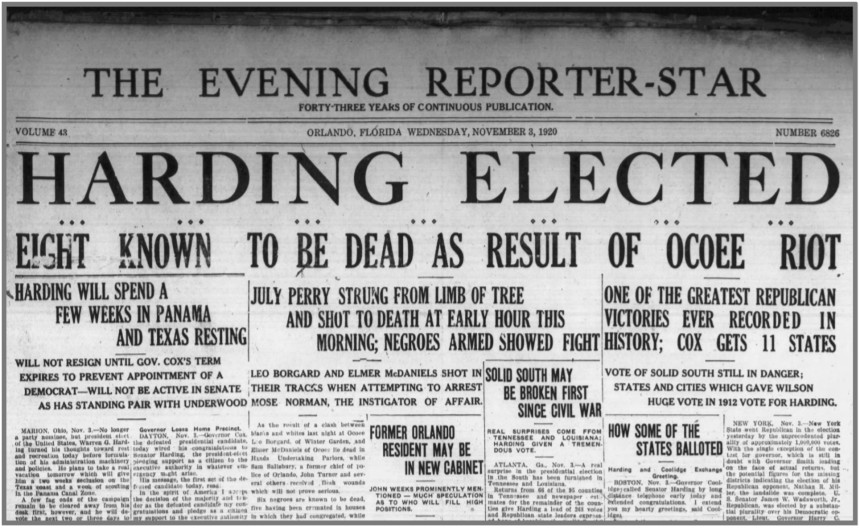

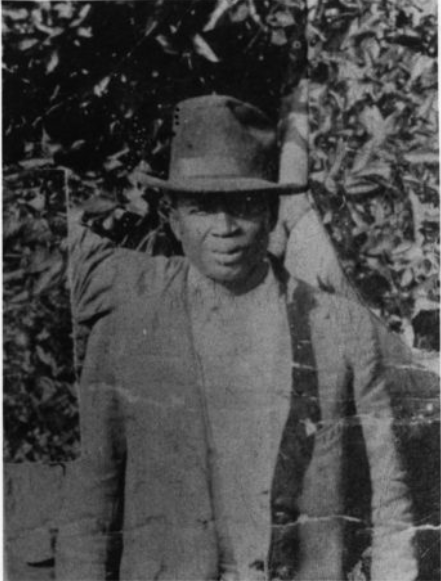

On November 2, 1920, as voters across the country went to the polls to decide a presidential election between two Ohio politicians, Republican Senator Warren G. Harding and Democratic Governor James M. Cox, violence erupted in the Florida town of Ocoee. Local African-American farmer Mose Norman tried to exercise his Constitutional right to vote, and was turned away twice under the pretense of the state’s Jim Crow efforts to disenfranchise black voters. An angry white mob then pursued Norman, laying siege to the home of another man, Julius “July” Perry. Perry fired on the attackers in self-defense, and the mob seized upon that action to terrorize the town’s Black community, eventually killing Perry and more than fifty other African-American residents, burning down homes and businesses, and forcing much of the rest of the community to flee the town.

The Ocoee massacre, known as the “single bloodiest day in modern American political history,” had its roots in multiple historical trends. Like states throughout the Jim Crow South, Florida had developed in the 50 years since the 15th Amendment’s ratification numerous legal measures and social practices intended to make it impossible for African Americans to vote. But those longstanding voter suppression measures were complemented by a much more immediate, violent threat of force: the day before the election, members of the newly resurgent, 2nd Ku Klux Klan had marched through Ocoee, proclaiming through megaphones that “not a single Negro will be permitted to vote.” And no 1920 act of racial terrorism can be separated from the prior year’s epidemic of such violence, the year-long series of lynchings and massacres that came to be called the “Red Summer of 1919.”

Those factors help us understand the divisions and discriminations at the heart of American culture in 1920. But on the 100th anniversary of the Ocoee massacre, and as we approach another election day, that specific historical event can also help us to better recognize an overarching, profoundly relevant American trend: the way in which voter suppression has consistently gone hand in hand with racial terrorism to prop up white supremacy.

In recent years, we’ve started to do a better job of remembering the history of white supremacist racial terrorism in America through such vehicles as public memorials and pop culture texts, including horrific individual events such as the 1921 Tulsa massacre and the century-long lynching epidemic. But too often the stunning brutality and destruction of those acts of violence can make them seem like impromptu explosions, perhaps reflecting consistent undercurrents of racism but not the result of purposeful, extensive, organized political planning.

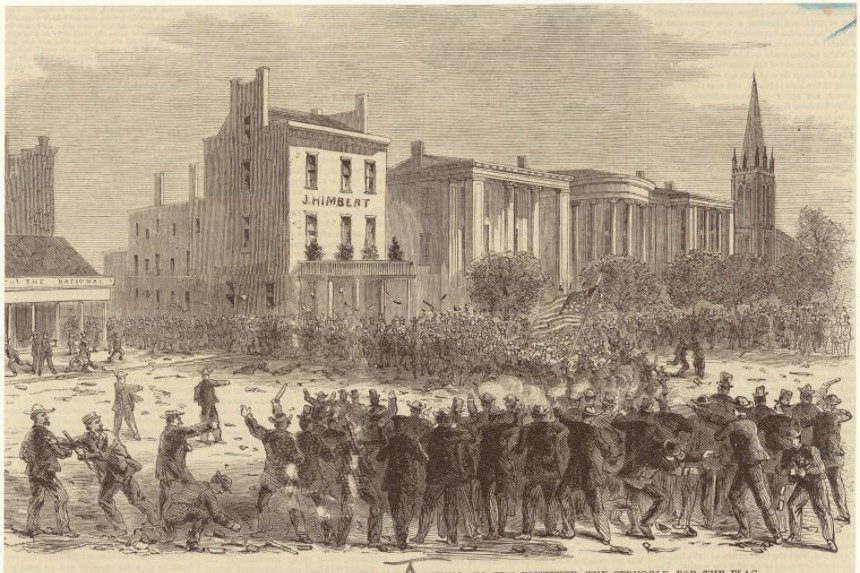

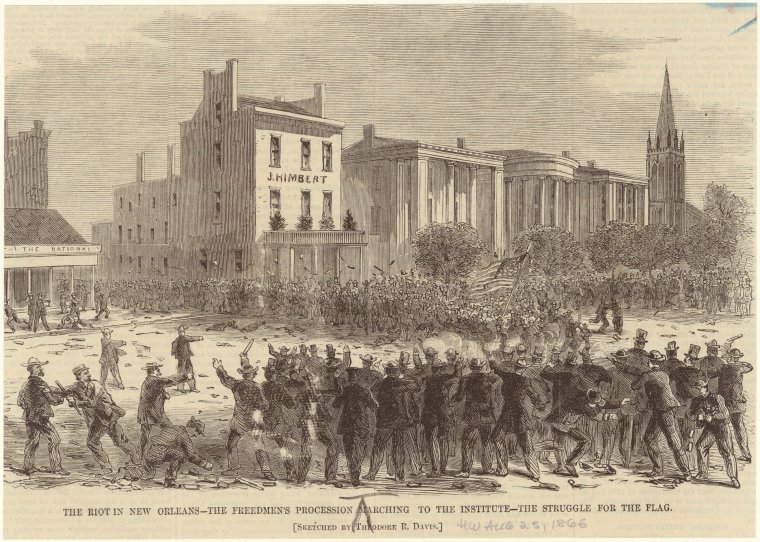

Yet the truth is that these acts of racial terrorism have consistently been tied to planned, organized, systematic plans for voter suppression and related political agendas, as illustrated by not just Ocoee in 1920, but also three prominent 19th century massacres and one from the Civil Rights era. The July 30, 1866 New Orleans massacre began when white supremacists attacked 130 African-American residents marching toward the Louisiana Constitutional Convention at Mechanics’ Institute; the state legislature had passed a series of Black Codes barring Black men from voting (among many other discriminatory effects), and the marchers were hoping to join the Convention to advocate for their rights. New Orleans’ newly re-elected Confederate mayor, John T. Monroe, led a group of ex-Confederates, police officers, and other white supremacists to attack the marchers, starting a massacre that would end with more than 200 African-American Union Army veterans and another 200+ Black civilians killed.

Despite such racial terrorism, African Americans continued to exercise their Constitutional right and active patriotic goal of voting, and were consistently met with extensive suppression and violence. On November 3, 1874, African-American voters at the polls in Eufaula and Spring Hill, towns in Alabama’s Barbour County, were attacked by members of the widespread white supremacist organization The White League; seven African Americans were killed and another 70 wounded. The Barbour County massacre was one of many such events throughout the South on that 1874 election day, a planned campaign of voter suppression and violence after which League-affiliated officials also threw out legitimate votes for Republican candidates and helped install sympathetic Democratic officials in their place (a shift often defined as the beginning of the end of Federal Reconstruction).

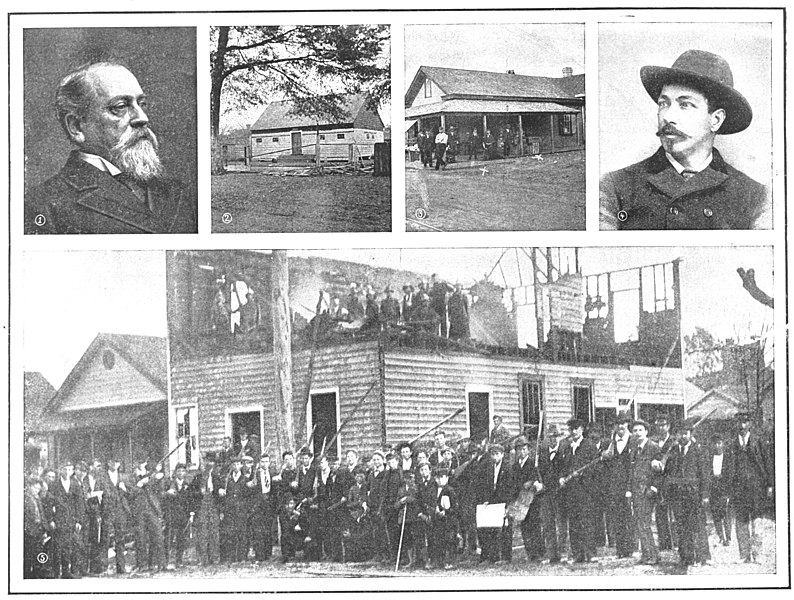

The November 1898 Wilmington (North Carolina) coup and massacre originated from even more overtly organized voter suppression goals. By late 1898 Wilmington was one of the last communities in North Carolina (and the entire Jim Crow South) not governed by white supremacists — the so-called “Fusion” Party, featuring African-American political figures and their Republican and Populist white allies, had in the 1896 election held on to many of the city’s positions. White supremacists targeted the next election day, November 8, 1898, as an occasion to reverse that trend by force and violence: planning for months an extensive program of both voter suppression and systemic violence, alongside an accompanying propaganda campaign in the media, that resulted in both a coup d’etat and a massacre that devastated the city’s African-American community.

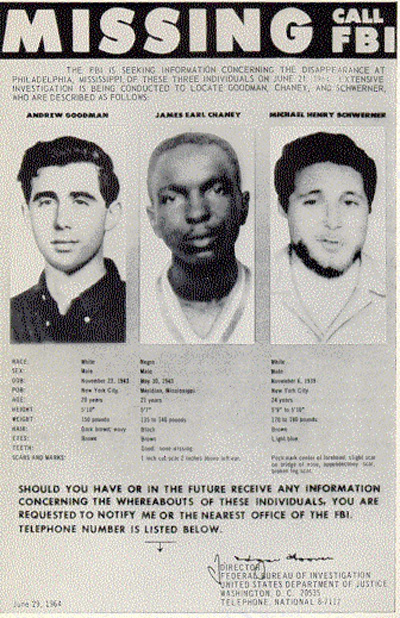

One of the latest documented lynchings, the infamous June 1964 murder of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner near Philadelphia, Mississippi, was similarly interconnected with voter suppression. The three men were working for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) as part of its Freedom Summer campaign to register African-American voters in Mississippi and throughout the South, and were on their way to a registration event at a local church when they were pulled over by local law enforcement. An extensive FBI investigation determined that members of the Philadelphia Police Department, the Neshoba county sheriff’s office, and the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan subsequently abducted and killed the men. The collaboration between those official and domestic terrorist organizations doesn’t simply reflect their overlapping membership; it also illustrates that the murder of these voting rights activists was part of a political campaign to suppress African-American votes and keep these white supremacist forces in power.

Throughout American history, those who have fought for the right to vote have had to do so in direct opposition to some of the nation’s most powerful forces, including white supremacist suppression and violence. Those battles continue into the 21st century, and as we continue to fight for and to exercise the right to vote, it’s vital that we remember the foundational and consistent ties between voter suppression and white supremacist racial terrorism.

Featured image: The New Orleans Massacre (Artwork by Theodore R. Davis for Harpers Weekly / Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now