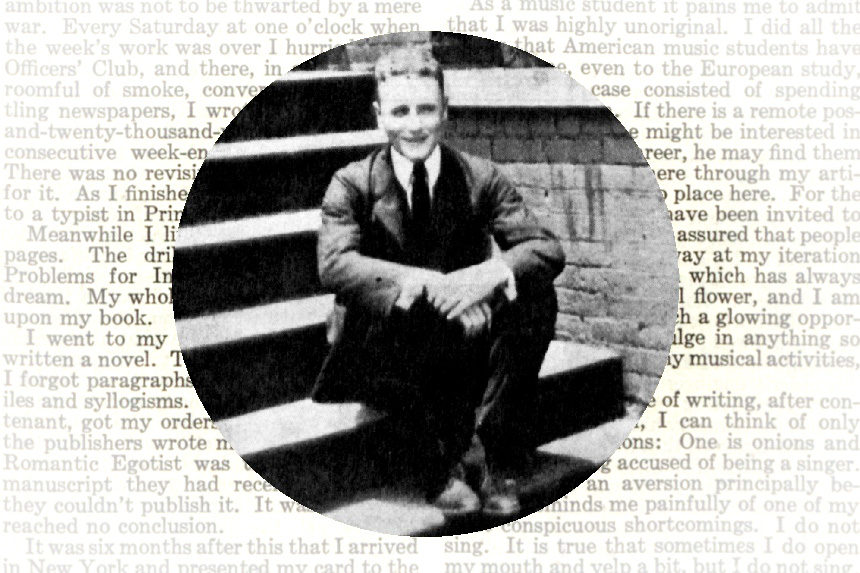

Amidst the gleam of his emerging career, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote a short personal essay for the Post’s “Who’s Who — and Why?” section letting the magazine’s readers in on where this new writer had come from. The year, 1920, had been a momentous one for Fitzgerald, having published his first novel, This Side of Paradise, along with several short stories: first, “Head and Shoulders,” and “The Ice Palace,” and later the famous “Bernice Bobs Her Hair.” The “jazz age” author offers distant comments on his life hitherto as though it were all an ironic dream leading him to inevitable success. Fitzgerald would muse about his own life for the magazine many more times in the years to come, penning “How to Live on $36,000 a Year” in 1924 and “One Hundred False Starts” in 1933.

Originally Published on September 18, 1920

The history of my life is the history of the struggle between an overwhelming urge to write and a combination of circumstances bent on keeping me from it.

When I lived in St. Paul and was about twelve I wrote all through every class in school in the back of my geography book and first year Latin and on the margins of themes and declensions and mathematic problems. Two years later a family congress decided that the only way to force me to study was to send me to boarding school. This was a mistake. It took my mind off my writing. I decided to play football, to smoke, to go to college, to do all sorts of irrelevant things that had nothing to do with the real business of life, which, of course, was the proper mixture of description and dialogue in the short story.

But in school I went off on a new tack. I saw a musical comedy called The Quaker Girl, and from that day forth my desk bulged with Gilbert & Sullivan librettos and dozens of notebooks containing the germs of dozens of musical comedies.

Near the end of my last year at school I came across a new musical comedy score lying on top of the piano. It was a show called His Honor the Sultan, and the title furnished the information that it had been presented by the Triangle Club of Princeton University.

That was enough for me. From then on the university question was settled. I was bound for Princeton.

I spent my entire Freshman year writing an operetta for the Triangle Club. To do this I failed in algebra, trigonometry, coordinate geometry, and hygiene. But the Triangle Club accepted my show, and by tutoring all through a stuffy August I managed to come back a Sophomore and act in it as a chorus girl. A little after this came a hiatus. My health broke down and I left college one December to spend the rest of the year recuperating in the West. Almost my final memory before I left was of writing a last lyric on that year’s Triangle production while in bed in the infirmary with a high fever.

The next year, 1916-17, found me back in college, but by this time I had decided that poetry was the only thing worthwhile, so with my head ringing with the meters of Swinburne and the matters of Rupert Brooke I spent the spring doing sonnets, ballads and rondels into the small hours. I had read somewhere that every great poet had written great poetry before he was 21. I had only a year and, besides, war was impending. I must publish a book of startling verse before I was engulfed.

By autumn I was in an infantry officers’ training camp at Fort Leavenworth, with poetry in the discard and a brand new ambition—I was writing an immortal novel. Every evening, concealing my pad behind Small Problems for Infantry, I wrote paragraph after paragraph on a somewhat edited history of me and my imagination. The outline of 22 chapters, four of them in verse, was made, two chapters were completed; and then I was detected and the game was up. I could write no more during study period.

This was a distinct complication. I had only three months to live — in those days all infantry officers thought they had only three months to live — and I had left no mark on the world. But such consuming ambition was not to be thwarted by a mere war. Every Saturday at one o’clock when the week’s work was over I hurried to the Officers’ Club, and there, in a corner of a roomful of smoke, conversation and rattling newspapers, I wrote a one-hundred-and-twenty-thousand-word novel on the consecutive weekends of three months. There was no revising; there was no time for it. As I finished each chapter I sent it to a typist in Princeton.

Meanwhile I lived in its smeary pencil pages. The drills, marches and Small Problems for Infantry were a shadowy dream. My whole heart was concentrated upon my book.

I went to my regiment happy. I had written a novel. The war could now go on. I forgot paragraphs and pentameters, similes and syllogisms. I got to be a first lieutenant, got my orders overseas — and then the publishers wrote me that though The Romantic Egotist was the most original manuscript they had received for years they couldn’t publish it. It was crude and reached no conclusion.

It was six months after this that I arrived in New York and presented my card to the office boys of seven city editors asking to be taken on as a reporter. I had just turned 22, the war was over, and I was going to trail murderers by day and do short stories by night. But the newspapers didn’t need me. They sent their office boys out to tell me they didn’t need me. They decided definitely and irrevocably by the sound of my name on a calling card that I was absolutely unfitted to be a reporter.

Instead I became an advertising man at 90 dollars a month, writing the slogans that while away the weary hours in rural trolley cars. After hours I wrote stories — from March to June. There were 19 altogether; the quickest written in an hour and a half, the slowest in three days. No one bought them, no one sent personal letters. I had 122 rejection slips pinned in a frieze about my room. I wrote movies. I wrote song lyrics. I wrote complicated advertising schemes. I wrote poems. I wrote sketches. I wrote jokes. Near the end of June I sold one story for 30 dollars.

On the Fourth of July, utterly disgusted with myself and all the editors, I went home to St. Paul and informed family and friends that I had given up my position and had come home to write a novel. They nodded politely, changed the subject and spoke of me very gently. But this time I knew what I was doing. I had a novel to write at last, and all through two hot months I wrote and revised and compiled and boiled down. On September 15th This Side of Paradise was accepted by special delivery.

In the next two months I wrote eight stories and sold nine. The ninth was accepted by the same magazine that had rejected it four months before. Then, in November, I sold my first story to the editors of The Saturday Evening Post. By February I had sold them half a dozen. Then my novel came out. Then I got married. Now I spend my time wondering how it all happened.

In the words of the immortal Julius Caesar: “That’s all there is; there isn’t anymore.”

Featured image: The Saturday Evening Post, September 18, 1920

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now