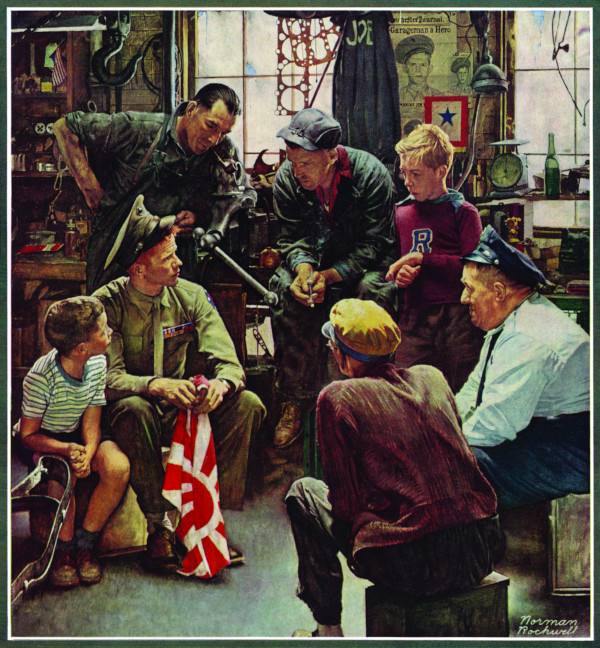

Homecoming soldiers were a popular subject for illustrators in 1945. But for this end-of-war cover, Rockwell took an unusual approach to capturing a veteran’s welcome home.

A traditional cover would have shown a G.I. standing tall and proud among civilian admirers, and Rockwell had produced a cover like that after the last war. It showed a tough, confident doughboy surrounded by adoring younger boys. But at the end of this world war, he gives us a slim, young Marine sitting on a box. As if to emphasize his youth, he is seated beside a little boy who is mimicking his pose.

The newspaper on the wall gives us his back story: The mechanic who’d enlisted for the war has now returned a hero, probably from the Asian theater, judging by the flag he is holding. But, instead of recounting tales of glory, he is looking up with a thoughtful, almost troubled expression at the boy who has just asked him a question.

Rockwell was a master at conveying the subtleties of human expression, and it’s clear his intention wasn’t merely to show a hometown boy back in familiar surroundings, but also to capture the newly returned veteran’s feeling of isolation — knowing he can never adequately convey to the folks at home the things he experienced in the war.

This article is featured in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: (Norman Rockwell / SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I registered at the age of 18 in ’58. And, yes, it was required, but I was glad to do so. It was a fact of life.

The heroics of the Marine were aptly characterized by Rockwell who presented him with the Silver Star for bravery and the Purple Heart for wounds received while giving him the youth of a boy just barely out of High School .

Rockwell’s art drew tears from this 78 year old grandmother. Am currently reading a book about American civilians of the Borneo/Philippines prisoners of war experiences oddly enough, and what they endured. This nation can NEVER repay its military personnel for what they did and what they do to protect the rest of us from evil.

Many Thanks for this beautiful and well-written story. Norman Rockwell was truly the greatest in portraying the subtleties of human feelings, as I well remembered even when I was a boy.

This young Marine is likely still overwhelmed by his experiences in the newly ended war he can’t possibly convey, and the men and boys around him likely wouldn’t understand even though they might try. Having said that though, the two men in the bottom right corner may have been in World War I, and would be able to relate. The men at the top too young for WWI, and past the age for WWII.

The older boy likely could later have been in the Korean War of 1950-’53, the younger one probably not. When you’re born has so much to do with your destiny. I’ve long been aware I was born in the middle of the only 5 year period where American males did NOT have to register for the draft (1/1/55-12/31/59) but after that, to the present, yes.