Generation X readily acknowledges the films of John Hughes as bedrock cultural experiences of their ’80s and ’90s youth. At the same time, a number of other films would represent a darker undercurrent of that generation’s experiences, far away from fictional Shermer, Illinois, including Tim Hunter’s River’s Edge (1986), Michael Lehmann’s Heathers (1989), and Allan Moyle’s Times Square (1980). Put off by parts of his Times Square experience, Moyle resolved not to direct again, but ten years later, he was back behind the camera for a film he’d written about alienation, depression, the burden of expectation, the exploitation of kids by school officials, and a primordial version of today’s internet culture. That film was Pump Up the Volume, a film both uniquely of its time while being many steps ahead of it.

Moyle first drew notice for 1980’s Times Square, a film that he co-wrote the story for and directed. The movie was produced by Robert Stigwood, famous for managing The Bee Gees and Cream, producing for the stage with shows like Hair and Jesus Christ Superstar, and producing films like Saturday Night Fever and Grease. Aware of the punk and new wave scenes that had already coalesced in New York City, Stigwood saw an occasion to produce another huge double-album soundtrack. Moyle just wanted to tell his story about two young women finding solace in each other and music. Frustrated to the point of quitting over Stigwood’s demand for more musical sequences, Moyle quit the movie before it was done. Stigwood got his musical scenes, but also cut some of the more emphatic lesbian overtones of the relationship between the two main characters. The resulting soundtrack turned out to be a tremendous artifact of its time, featuring acts like The Ramones, Roxy Music, The Cure, XTC, Lou Reed, The Patti Smith Group, Gary Numan, Talking Heads, and Joe Jackson. The film has since developed a cult reputation, but the overall situation and its failure drove Moyle from movies for a decade.

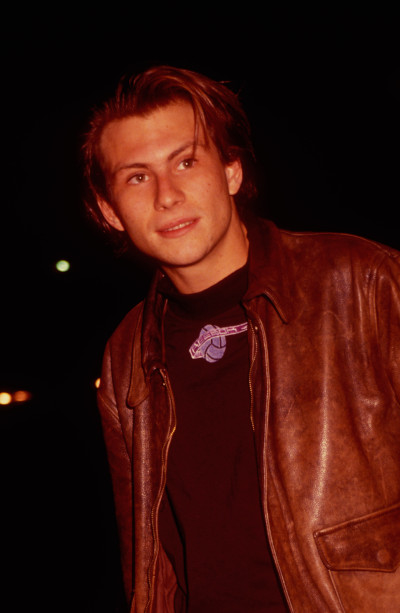

When he returned, it was with a script that he had originally started as a novel. The story concerned a pirate radio personality who was connecting with a teen audience by being real and foul-mouthed while playing music that related to an outsider sensibility. SC Entertainment out of Toronto decided to develop the movie, and they managed to talk Moyle into directing again. Still reluctant, Moyle said he’d walk if he couldn’t get the right lead; that turned out to be Christian Slater, who displayed some of the qualities that Moyle was looking for with his turn in Heathers.

The trailer for Pump Up the Volume (Uploaded to YouTube by Warner Bros.)

Released in August 1990, Pump Up the Volume is definitely of its time. It exists in a space just prior to the advent of the World Wide Web. While pay services like Prodigy and CompuServe were in use, there were still wide portions of the U.S. that hadn’t even heard of email. Comically large “Zack Morris” mobile phones existed, but weren’t remotely in the kind of widespread use that would follow later in the ’90s. That’s part of what makes the pirate radio station concept so appealing; teens really did listen to the radio in the ’80s, and that, along with both mainstream and underground music magazines, was one of the ways that kids (especially those in outsider social groups) learned both about new music and social issues. Ads in magazines like Maximumrocknroll and other avenues enabled a healthy tape trading culture, wherein teens would mail each other music or videotapes of concerts and club shows to facilitate the spread of bands they liked.

And that’s reflected in the broadest theme of the film: communication. Mark Hunter (Slater), a smart new student whose father works for the school district, is a loner and has trouble connecting, so he creates his shock-jock persona, alternately called “Happy Harry Hard-On” or “Hard Harry” and begins talking about everything that’s bothering him personally and socially behind the anonymity of radio and a voice modulator. For Mark, it’s initially about the release, but then he begins to realize that people are actually listening.

This taps into and opens up a wide range of problems as seen through a variety of other teen characters. One character struggles with the weight of academic expectations that’s been put upon her, and begins buckling under that pressure. Another finds himself expelled for suspicious reasons and protests to get back into the school. When Mark calls a listener, he winds up trying to talk him down from committing suicide, but fails. This activates the parents of the community, but they still miss the point that they aren’t connecting with their own children. What’s worse, people in the school administration have actually conspired to kick out kids that are struggling on standardized tests in order to make the school look better (and to keep receiving funding). These were real issues. They’re still real issues.

You can read Mark’s radio show, the affinity that kids have for it, and the broken communication between generations as a fairly savvy forerunner of internet culture. You can substitute “amateur radio” for “YouTube” or “TikTok” or “Snapchat” and still tell elements of the same story. That’s one of the reasons that film was strikingly different and remains resonant, because as good as John Hughes was at presenting outsiders, this hits in a more cutting way.

On The Sam Roberts Show, Christian Slater said he wants to be remembered for Pump Up the Volume. (Uploaded to YouTube by notsam)

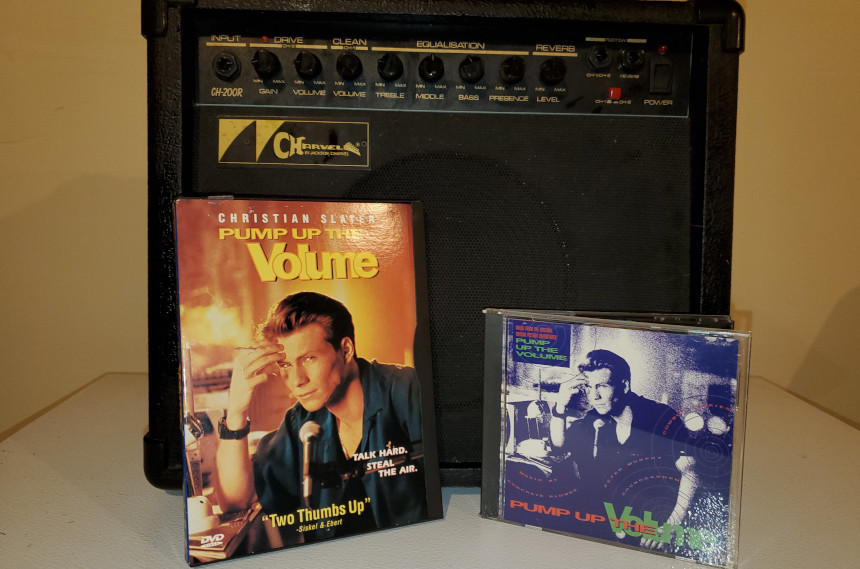

Moyle also managed to be ahead of the curve with his soundtrack, just like he was with Times Square. In the keynote address that he gave at South By Southwest (SXSW) in 2013, Dave Grohl hilariously recalled how absurd it seemed in 1990 that Nirvana and alternative music might break through to the mainstream, going as far as to read the Billboard Top Ten songs of that year. And yet, that’s the kind of music that fills Mark’s show and the Pump Up the Volume soundtrack. Moyle and company understood that outsiders connect to outsider music, and thus the film was populated with songs by The Pixies, Soundgarden, Sonic Youth, Concrete Blonde, Cowboy Junkies, and more. Ironically, a number of those bands would begin experiencing broader awareness that year, and some, like Soundgarden, would burst into actual stardom during the following year’s alternative explosion. Concrete Blonde’s contribution was a cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Everybody Knows;” in the film, Mark uses Cohen’s version to open his radio shows until the climactic scene when he uses the cover. The album peaked at #50 on the Top 200.

Ultimately, the film was not a huge success in theatres. Like a number of movies of the time, it found a second life on video. Moyle stayed in film this time, and would go on to make another music-centered and much-loved cult classic in 1995, Empire Records. The thing that remains important about Pump Up the Volume is that it tried to be about something, and it succeeded. It shows that teens have a much deeper life of complexity and problems than parents and authority figures give them credit for, and that simple and non-judgmental communication, no matter how loud, might be the best first step to alleviate those issues.

Featured image: The DVD and film soundtrack of Pump Up the Volume (Photo by Troy Brownfield. Film & DVD ©New Line Home Entertainment/Warner Bros.; CD & Soundtrack ©MCA Records/Universal Music Group; writer’s nearly indestructible Guitar Amplifier ©Charvel).

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

My 3rd sentence restructuring in paragraph 4 got messed up after I clicked POST I’m sorry to say. I meant it to say:

This makes the notion of saying (in ’90) that Nirvana and other ‘alternative’ music would not become mainstream, ridiculous!

‘Pump Up The Volume’ was one of the few films I went to see in 1990, aside from ‘The Grifters’. I liked the film quite well for many of the relatable reasons you mention, especially dealing with school and authority; a lot of what you mention in paragraph 5. Having to memorize info on subjects I wasn’t interested in to regurgitate back on tests was something I loathed in particular. Education’s demented ONLY judge of one’s intelligence.

The film admittedly was aimed for Gen-X of which I’m not a member. On paper I’m a member of the one before, but don’t relate to it because I can’t. I don’t remember the U.S. before JFK was assassinated like Gen-X and later, but can remember the event itself from 6 1/2 like those older to this day, every day, and it’s still painful. Most of my friends are born between from 1967-’72 and it’s as if there’s no age gap. I have more in common with them than a lot of people my own age. Go figure, right? That doesn’t make sense? Well very little in life otherwise “makes sense” either, so why would that be any different?

I got a lot of insight from the Sam Roberts interview that 1990 was one of the last years (because of technology) that this film could have taken place, when the radio was still a dominant media, heavily listened to. He talks of everything being all over with. Watching the film then I knew it was true, and 30 years later even more so. The core message of the film is even MORE timely now.

The soundtrack is really good too. By 1990 “outsider” music was pretty much all there was. The whole continuous run of ‘rock ‘n roll’ from 1955-’86 was long gone by ’90. This makes the notion saying (in ’90) that Nirvana and other ‘alternative’ music would not become mainstream! Their heads must have been up their; up in the clouds to keep it nice here. The soundtrack for ‘Volume’ worked for the film, and me. In the car nowadays I enjoy Sound garden, Pearl Jam, Smashing Pumpkins, and more from the ’90s in a different light than I did at the time. Sheryl Crow is my favorite artist of the ’90s-present, so I’ll always pump up the volume for her.